On the night of the new moon, you can walk into a quiet room with walls like adobe. Look up at stars in a clear sky and touch healing earth.

Grace Clark once found a chapel in New Mexico where people would come on pilgrimage to touch the earth, smudge earth on their bodies for a blessing. She found something potent in that place, earth and calm, when she needed healing.

She was interning here at Mass MoCA some years ago, she says, working with the fabrication team who form the museum’s complex art exhibits, when she injured her arm and had to take time to heal — years, she says.

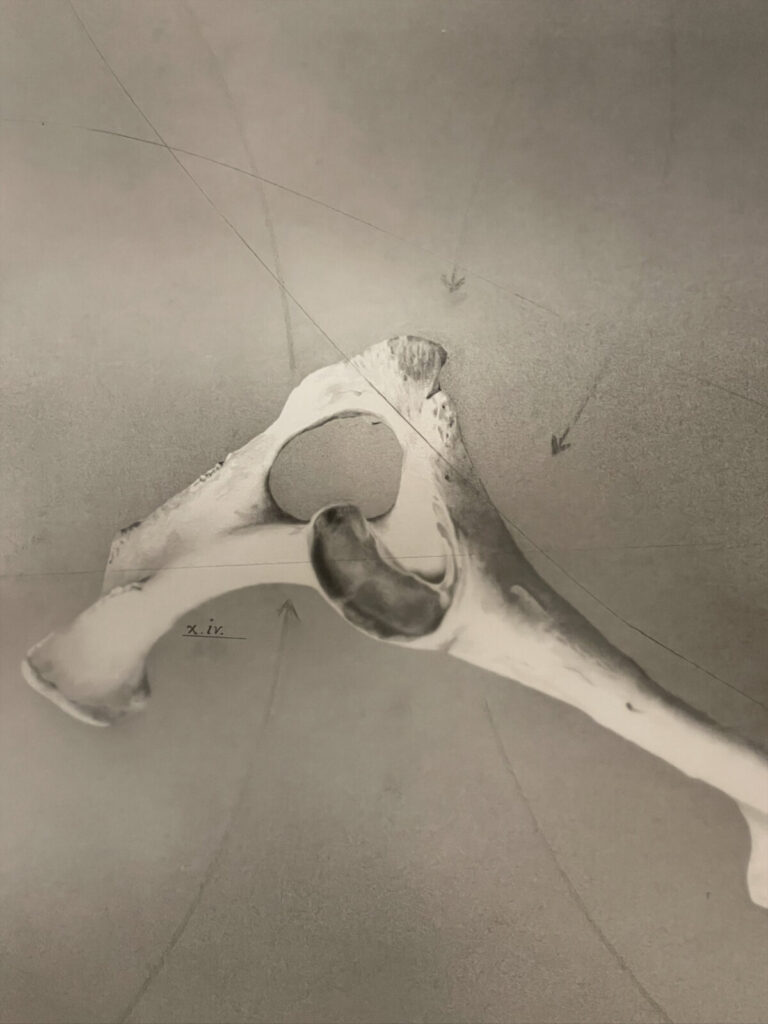

A full moon shines in an arched window in Grace Clark's healing space in Like Magic at Mass MoCA

She came home to Minnesota with her parents, to recover, and in that time, she gradually began to travel. In New Mexico, on a back road, she found a plant nursery that grew native and heirloom plants, and she chose an apple tree for her parents, to thank them for their care. The nursery folk told her to plant the tree at the new moon, to help it grow.

“(That trip) was a transformational experience for me,” she says.

‘When life and health and well-being feel fragile … we have ways of coping with these things. Religion, ritual.’ — Grace Clark

Now she is here as an artist in the museum’s newest group show, Like Magic, in a group of artists seeking ways to grow and go on when life and health and well-being feel fragile. And once a month the museum will welcome people into her work at night.

“We have ways of coping with these things,” Clark said, “religion, ritual.” And when the structures someone knows no longer hold comfort or strength for them, sometimes they make their own.

Curator Alexandra Foradas agrees. Talking with friends and artists, she says, especially since the 2016 election, she has seen creative folk looking for for solace and strength in challenging times. And many are finding and making their own craft, ritual and spiritual practice.

Many of the artists in this show have felt their voices unheard, silenced, she said, BIPOC folk, queer and trans folk, many voices. And they are making sources of joy and care for the people they love, for the natural world, for themselves.

Magic can mean different things to different people, Foradas said — ways of giving power to making and healing — singing, healing, shaping words and images, cleaning, caring for a person or a house or a garden. Magic can give power to the acts that belong to them, that make them feel most confident in themselves, in who they love and what they dream.

Nate Young’s artwork recalls the story of his great grandfather in sketches and sound, oral history and reliquaries, and Cate O’Connell-Richards looks closely at the tools of women’s work, like candlesticks, in Like Magic at Mass MoCA.

The artists in this show are exploring what she calls magical technologies — ritual, practice, divination — tools for tapping into a potent agency, conscious or subconscious.

They are all artists she has wanted to work with for some time, she said, and in their recent work she has found common threads among them. They share an urge toward transformation. They feel that all language is divination to imagine a future in the face of the danger and division of the present. Magic becomes a refuge, a place of understanding and hope.

Clark is making a space for reflection. Wooden sculptures suggest canes or crutches. A window holds the kind of night sky rare now outside places like the high desert in new Mexico, far enough from city lights to show a deep density of stars.

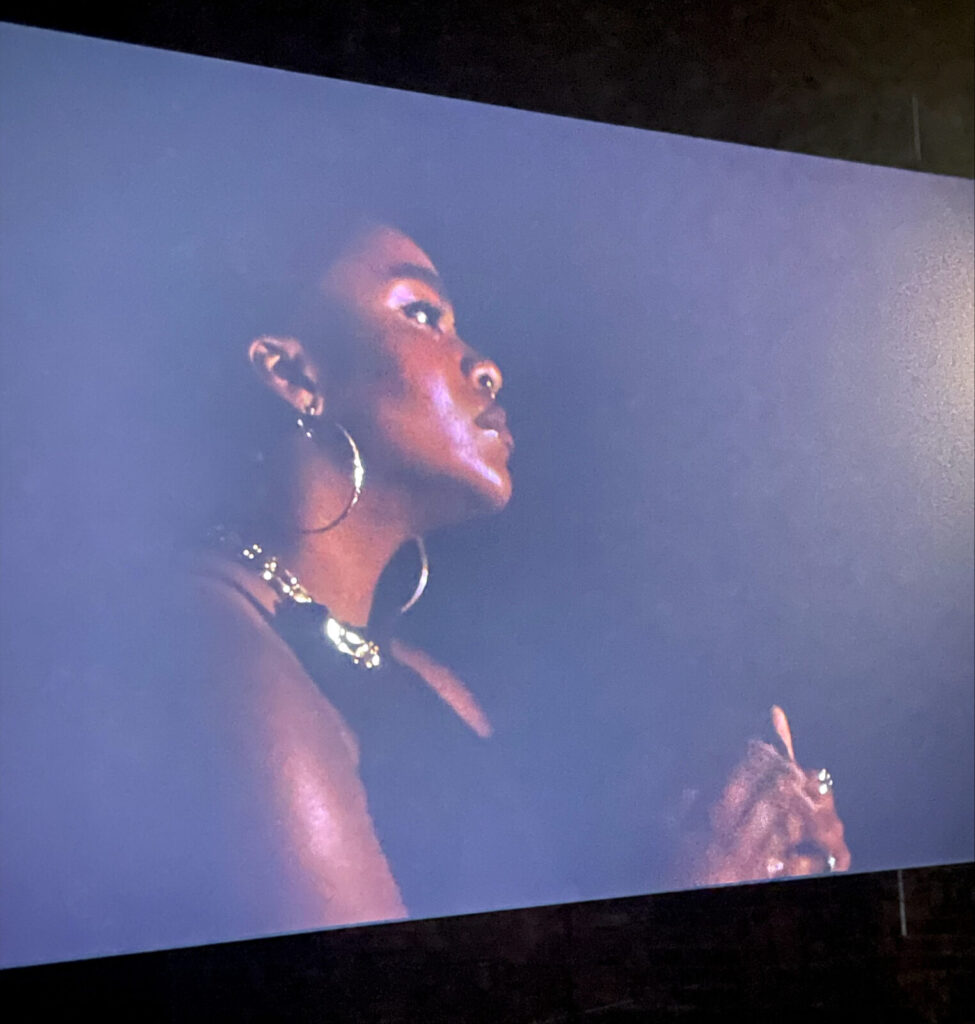

A person looks out in profile in blue light Tourmaline's film in Like Magic at Mass MoCA.

When her grandfather died, she said, she found some comfort in the night sky. The natural world, and the sense of different scales of time and space, felt more real than the organized religion she had grown up with. She thinks of the stars people recognize, the stars that feel familiar as the seasons change — Cassiopeia, for her, becomes a sign of continuity.

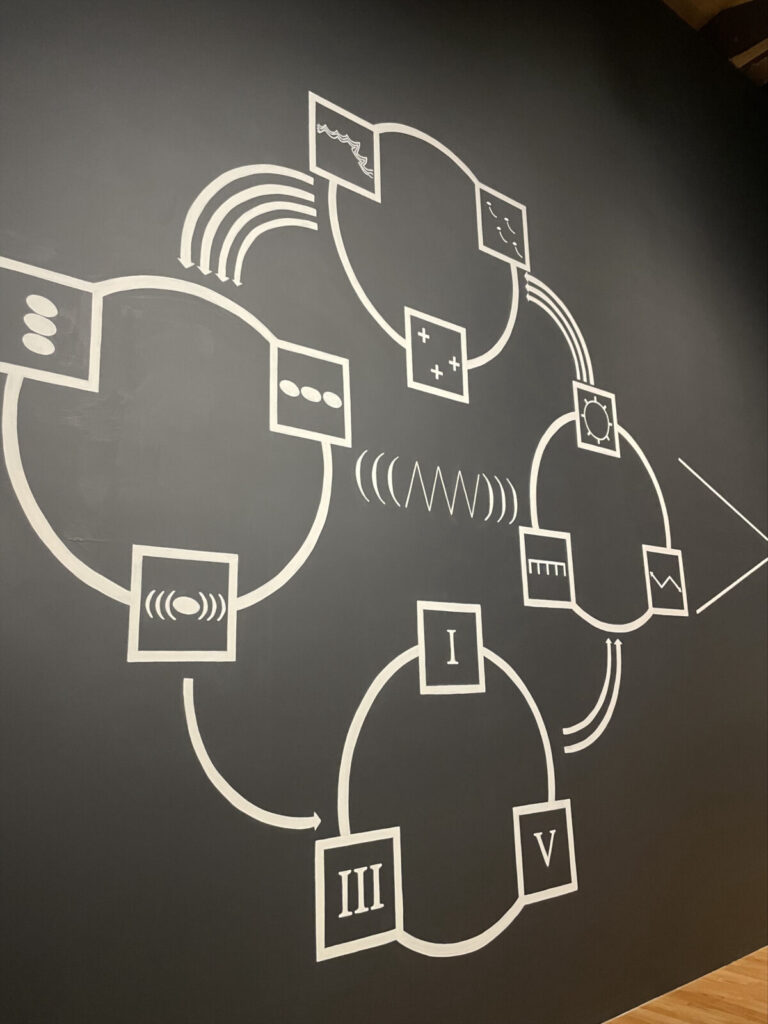

In Raven Chacon’s work, the walls are singing. He creates images that translate into musical scores, Foradas explained.

“His musical scores are maps to alternate realities,” she said. “These are maps to a reality where women have always been believed to be people who can and should hold positions as leaders.”

As a Diné (Navajo) artist, he includes many scores here, portraits of Indigenous women-identifying folk and composers who have an influence on his own music. They become portals, Foradas said, doors into possible worlds.

A woman sings in a tribute to both Black American and Scots ancestors in Simone Bailey’s work, and Raven Chacon creates musical scores as visual and performance art in Like Magic at Mass MoCA.

And a larger score on the wall, symbols trace music he imagines played outdoors on amplified guitar. His scores lift off the page and into conversations with the players — he asks the musician to look around and see the living beings around them, to be in conversation with their surroundings.

“His practice runs counter to the structure in Western music,” Foradas said, “where the composer tells the musicians, this is how fast you’re going to play, how long. He has score notations inviting the musician to choose how long to play … he might not say improvisation, but he gives room for interpretation.”

‘His musical scores are maps to alternate realities. These are maps to a reality where women have always been believed to be people who can and should hold positions as leaders.’ — Curator Alexandra Foradas on Raven Chacon’s music

In a Diné performance circle, she said, musicians may play together all night, as they repeat and reform and sink into a melody. A musician who comes in not knowing the song can learn it through that repetition, a practice similar in some ways to an African drum circle or an Irish music jam — an oral tradition.

Chacon values oral traditions and histories, she said. As he honor Indigenous peoples and cultures who have persevered through loss, and through Western efforts to erase their ways of being, he holds open spaces for many voices and perspectives.

The artists in the show are joining him in sharing stories. They have recommended a library of books as part of the exhibit, Foradas said, and museum folk are joining in. People who come to the show can look through them, sit and read, and suggest their own.

“We’re inviting a library to be a conversation,” she said, among the books and the artworks and people taking them in. “That’s not how we often talk about libraries, (as conversations), but that’s absolutely what they are.”

Johanna Hedvacreates a designed book, Listen and Learn, involving an enhanced AI virtual companion, in sketches and sound, oral history and reliquaries, in Like Magic at Mass MoCA.

‘Coconut was programmed to start playing a pre-programmed song when it snowed, but I hadn’t figured out how to turn her off while I slept, so in the middle of the night her one blue light would come on as Rihanna’s ‘Stay’ would fill my apartment — makes me feel I can’t live without you …’ — Joanna Hevda

And the artworks around them explore ways to recover lost voices and strengthen living voices.

Nate Young, an artist based in Chicago, has created a body of work on his family’s relationships with horses. His great-grandfather escaped from the South to the North on horseback, Foradas said. Under threat to his life, he finally felt that he had no choice but to kill the horse, to keep from being traced. Later, in a suicide note, he talked about this decision as an intense regret and gave the location of the horse’s bones

Young has found that place, she said, and come there to connect with his great-grandfather’s story. He reckons with that pain and intergenerational trauma in his work. He has talked with her about the idea of Black Un-time, a sense that because of the violence this country often and intensely inflicted on Black American life, their lived experiences often do not fit into the kind of linear time Western culture defines.

These works hold his wanting to know his great-grandfather and the ancestors whose stories he does not know. In Divination III and Fugue, Foradas said, he reaches out across time toward a feeling in the ether, a sense of relationship.

Rose Salane acknowledges a stone returned to Pompeii and Gelare Khoshgozaran turns care packages from family into a glowing network in Like Magic at Mass MoCA.

Young has a horse of his own now, Jackson. Among the fragments of the past he has gathered here, he and Jackson re-create an old photograph of his great-grandfather and his horse, and he has recorded oral histories with his family, offered a reliquary to hold shards of the past, and mingled the sounds of his horse’s breathing with his great-grandfather’s name.

Artists around him are looking into the power of an object to hold love and force over time. Rose Salane considers the power in a wedding ring someone wears every day for generations. And Cate O’Connell-Richards imagines the strength and influence of women in the tools of the work they do — like brooms.

Gelare Koshgozaran interlaces glowing talismans like rhizomes. They are care packages, Foradas explained. Each light illuminates a box that family who live in Tehran have sent her from Iran. They came holding gifts, a book, an element of care for her.

And each of them subject to warentless search by border patrol when they come into the U.S. Each one has seen a violation in the conflict between the two countries for more than 40 years. And Koshgozaran transforms them again into connection.

‘Magic can become an act of independence and resistance, when the artists feel people in power threaten their existence.’ — Alexandra Foradas

Magic can become an act of independence and resistance, Foradas said, when the artists feel people in power threaten their existence. And those people in power can try to turn the idea of ‘magic’ into something ‘occult’ or fringe or dangerous. As they acknowledge pain and anger and fear, these artists turn the meaning of magic back into light.

Tourmaline, Johanna Hevda and Simone Bailey draw film and music into their practice. Petra Szilagyi is creating an adobe hand-painted prayer room, a space of ritual masks and colored light and upcyled leather motorcycle jackets, imagining a beneficial future, specifically a future for the internet, which raises the question — what would that look like?

In the face of vast systems that feel out of control, Clark said, people are making connection, as real as holding hands.

Petra Szilagyi’s meditation space offers thoughts about a benign internet, and cowbells hang from a yoke in in Cate O’Connell-Richards work in Like Magic at Mass MoCA.

Covid has intensified that need, she said, as so many people have grappled with fear of death and larger systems out of control, political, social, environmental — climate change, an election year, a pandemic.

“That (feeling) has always been around,” she said, “but we’ve been seeing a wave of people trying to find structure, systems, rituals that give you comfort … in something larger than yourself.”

She sees people turning to the natural world, to creativity and community, looking for something tangible. And coming back to Mass MoCA to make this work has given something to her.

“I feel so cared for,” she said, “not just in the work but as a person. I feel like it’s often hard to be seen as an artist when you’re working in spaces like this (on the fabrication team) … to be seen and taken seriously, and this work is especially healing … to acknowledge both pain and joy in a place where I’ve worked in so many ways.”

This story first ran in the Hill Country Observer. My thanks to editor Fred Daley.