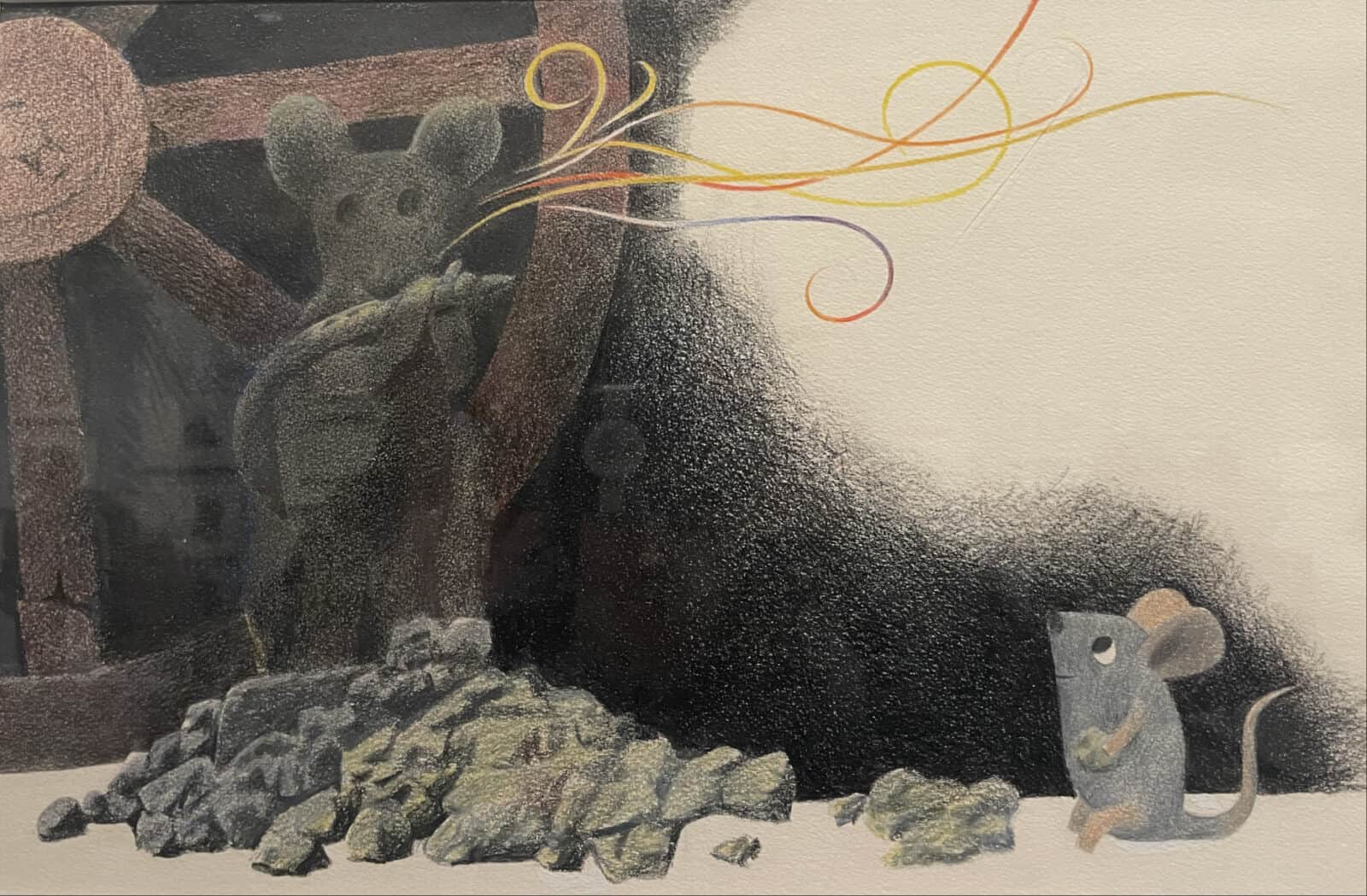

A young mouse gathers stories in the summer instead of corn. He feels the sun on the stone wall and listens to the wrens and the caterpillars in the milkweed. And in cold winter days he feeds his family’s minds and souls.

As an internationally known children’s book author, Leo Lionni can tell complex stories in bright strokes and rueful humor. His characters question their worlds with integrity and individuality, sometimes in ways that transform the people around them.

The Norman Rockwell Museum explores his visions this winter, as they open Between Worlds: The Art and Design of Leo Lionni, the first major American retrospective on his art and design, in collaboration with Annie Lionni, his granddaughter and steward of his legacy.

Her grandfather grew into an international figure after World War II, she said on the show’s opening night. He became one of the first illustrators to experiment with collage, and his children’s stories can carry deep undertones.

She came to the Rockwell, she said, wanting to offer a broad view of his life and the experiences that influenced his work. After some time as an architect herself, she has been representing her grandfather’s work for the last 25 years, including books and performances and traveling exhibits around the world.

Leo himself traveled the world, she said, all through his lifetime. He was born in 1910 in Amsterdam, an only child in a large family of aunts and uncles. He grew up surrounded by encouragements to creativity, as his work in the show reveals. In his room he would draw, paint and carve and fill glass jars with terraria, miniature natural landscapes.

He knew early that he wanted to be an artist, she said. One of his uncles taught him to draw, and as a child he explored museums, absorbing paintings. His uncles traveled, and his family had work at home by artists who here contemporary then — he knew familiarly a work by Marc Chagall.

Leo Lionni illustrates 'Frederick' in bright collage, as mice harvest corn in the fall woods and fields and one mouse dreams — Image courtesy of the Norman Rockwell Museum.

So he lived between the Netherlands and Brussels as a child, in the years of World War I. In the 1920s he moved to Philadelphia with his parents, and he finished high school in Genoa. And then, when he was 16, he met Nora Maffi. In 1931 they married, and they would remain together all their lives, for 68 years.

“She was his backbone,” Annie Lionni said in the galleries after the talk, warmly recalling her grandmother.

Leo and Nora moved to Milan in the first years of their life together, from 1931 to 1939, and there they saw the rise of fascism in Italy. Nora already had deeply personal experiences of the shift in power. Her father, Fabrizio Maffi, was an Italian senator and one of the early founding members of the Italian socialist party, Annie said, and as Mussolini came to power in 1922, Fabrizio Maffi was arrested.

“My grandmother spent most of her childhood with her only parent in jail,” Lionni said. “Her mother died when she was young.”

A young mouse listens to a sculpture playing music in the dark in Leo Lionni's illustration. Press image courtesy of the Norman Rockwell Museum.

When Nora married Leo, he was studying as an artist. He was surrounded by ancient mosaics and avant-garde abstraction — and even in the art world he was seeing the growing force of totalitarian rule. It would touch his family closely. Leo’s father’s family was culturally Jewish, Annie said, secular and liberal. And when Annie’s father was six years old, he could not begin school — Italy was the first fascist country to stop allowing Jewish children in the classroom. So the Lionnis left Europe for America in 1939, on the edge of war. And many of Leo’s closest family in the Netherlands also found ways through the war, though Annie has learned that others did not have that chance.

“Before the war there were a lot of Lionnis in Amsterdam,” she said on a podcast with the Illustration department as the Norman Rockwell’s show opened, “and … they were all killed in the war. They were all killed at Auschwitz and other places. They were all Jews, and they were our cousins.”

‘Before the war there were a lot of Lionnis in Amsterdam … They were all killed in the war. They were all killed at Auschwitz and other places.’ — Annie Lionni

Starting again in the U.S. with a family to care for, Lionni came to Philadelphia, where he had some family contacts from high school, and pursued a career in design and advertising illustration, here and then in New York. In Italy he had also earned a degree in economics, Annie said — his father had wanted him to go into business.

He found stability and recognition as art director for Time Life publications including their Fortune Magazine, and at the same time he was moving in a community of avant garde artists in New York.

‘Leo insisted on creating his own ideas.’ — said co-curator Steven Heller, co-curator of the retrospective

The show traces his growing relationships — he would commission younger artists including Andy Warhol and Eric Carle and work with the MoMA on publications for Edward Steichen’s Family of Man exhibit, and become art director of the independent Print magazine.

“Leo insisted on creating his own ideas,” said co-curator Steven Heller, co-curator of the retrospective and co-chair of the School of Visual Arts MFA Design / Designer as Author + Entrepreneur program in New York City.

In Lionni’s design work, and in his artwork, Heller finds humor and wit. Lionni explores montage and collage with whimsy and abstraction, he said, and a sense of essentials, calling to depths of experience in a few words and a few lines.

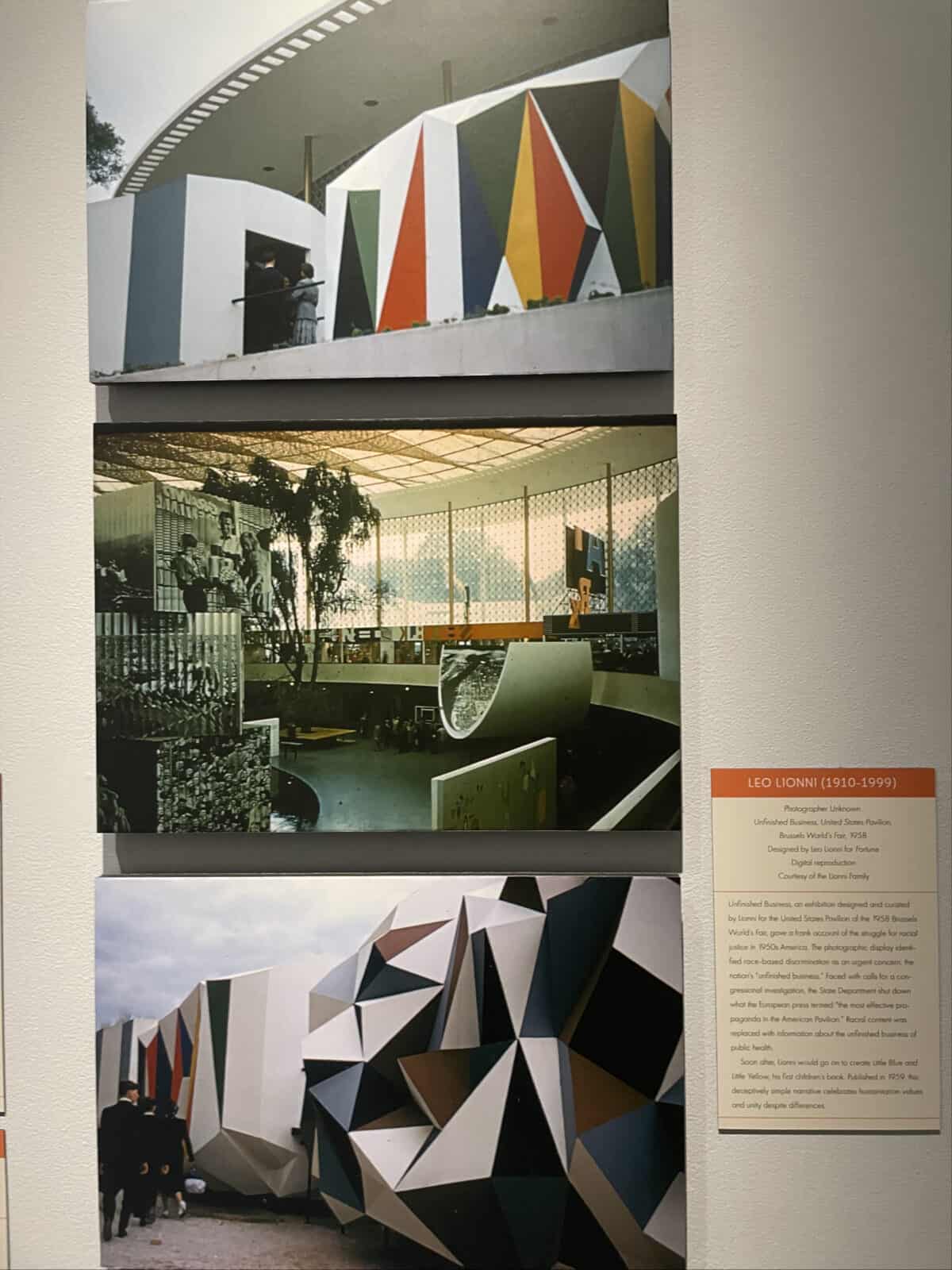

Photographs show Leo Lionni's pavilion in Pavilion at the Brussels Worlds Fair in 1958. Press image courtesy of the Norman Rockwell Museum

And then in 1959, at a time of international recognition, Lionni left his New York career. Annie traces an abrupt and clear shift in his focus. Through his design work, she said, he had the chance to create a Pavilion at the Brussels Worlds Fair in 1958. He imagined a set of three rooms — and he called them Unfinished Business.

He and the team who envisioned the pavilion wanted to expose America’s flaws honestly, Annie Lionni said, and talk about what the country was doing to change them. Henry Luce (founder of Time, Life, Fortune and Sports Illustrated) and the State Department gave Lionni the chance to imagine the installation in this light, and he created spaces looking at urban blight, environmental degradation — and prejudice, and segregation.

And three weeks after he opened this exhibit on an international stage, the U.S. government closed down the heart of it.

The Norman Rockwell show gives impressions of Lionni’s vision, in photographs of the rooms he imagined. The walls are rounded and tall enough to encompass a living tree. The ceiling is a skylight rayed like the sun. And along the walls a collage of newspapers show a current of events involving Civil Rights and the growing movement for freedom, for Black Americans, Indigenous Communities, immigrant communities and many more.

In these rooms, Lionni wanted to move from the present he saw to the future he hoped for, Annie said. In one broad image, young people hold hands in a ring, running and taking each other’s weight. They come from many backgrounds, laughing together.

When the rooms opened, politicians from the South erupted. They put Lionni under pressure to the extent of raising an international scene, Annie said. They put up a a sign saying “this does not represent the views of the U.S.,” and they intensified hostilities until the State Department shut down any part of the Pavilion that opened a conversation on tolerance and humanity.

Within the year after this confrontation, Lionni would leave his graphic design and art direction work in New York to create stories for children. Annie Lionni has often told the story of the train ride when her grandfather first told her and her brother a story with characters of torn paper, an idea that later evolved into his first book, Little Blue and Little yellow.

“My brother and I have often told that story,” she said — “but the important story is that the book came out just after the exhibit was closed down. Leo never said this, but I think all of his children’s books came from the shutting down of the pavilion.”

‘The important story is that the book came out just after the exhibit was closed down. Leo never said this, but I think all of his children’s books came from the shutting down of the pavilion.’ — Annie Lionni

“Leo recognized that the audience he most wanted to write for was the audience who would make the future, said Leonard S. Marcus, co-curator and a worldwide authority on children’s books and the people who create them.

With Little Blue and Little Yellow, Lionni would emerge into a new arc of his career, Marcus said. The seemingly quiet story follows a blue circle and a yellow circle who become friends. They share games and songs and ring-a-ring-a-roses — like the young people in the Pavilion. And when their colors begin to merge, their families at first don’t (or won’t) know them anymore.

“Leo’s work … is about vision,” Marcus said, “and understanding what children need to know about what it means to maintain yourself in the face of pressure.”

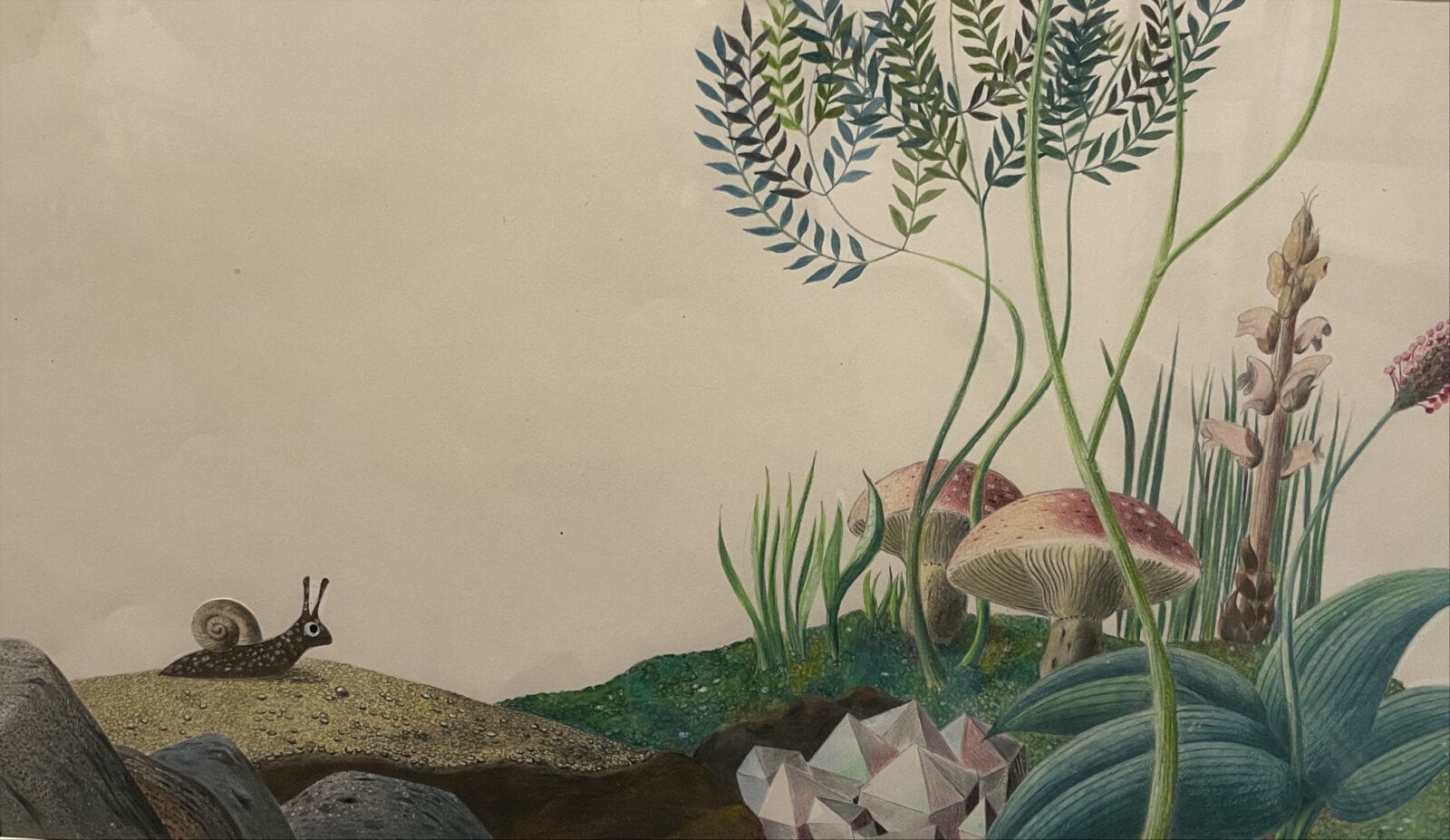

A snail travels through a forest bright wtih mushrooms and ferns in Leo Lionni's The Biggest House. Press image courtesy of the Norman Rockwell Museum

Lionni would go on to write more than 40 books for children, and he often began with a narrator who does not fit easily into the world around him — a mouse who dreams of painting, a bird born without wings — or a snail who wants the world’s largest house, without thinking that he will have to carry it with him.

“He’s always in love with the natural world,” Marcus said.

Frederick, the daydreamer and poet, sits on a stone wall on on sunny fall days. His family of mice are gathering food for the winter, and when he is distracted by the woods and fields and sunlight, they are impatient and frustrated with his impracticality. But on winter nights, the mouse poet will have stories to tell and songs to sing.

“Leo’s books, like Ezra Jack Keats’, form a kind of community,” Marcus said. “… A good book can slow time down for children. They can look with clarity at their own emerging daydreams and language.”

‘Leo’s work … is about vision and understanding what children need to know about what it means to maintain yourself in the face of pressure.’ — Leonard S. Marcus, co-curator of the retrospective

Lionni wanted to encourage children to explore what they can make and imagine, he said, to bring out a sense of play and explore the balance between one person and the people in their larger world.

He turned to collage, Marcus said, a form calling to many artists in the mid 20th century. After two world wars, the world had torn itself apart, and people were trying to pick up the pieces and reshape another and stronger sense of community.

In this time of his life, Lionni would explore new collaborations and connections in many places. He created album covers for South African nature songs by husband and wife musicians Marais and Miranda. He taught at Black Mountain College in North Carolina, Parsons School of Design, the Cooper Union in New York.

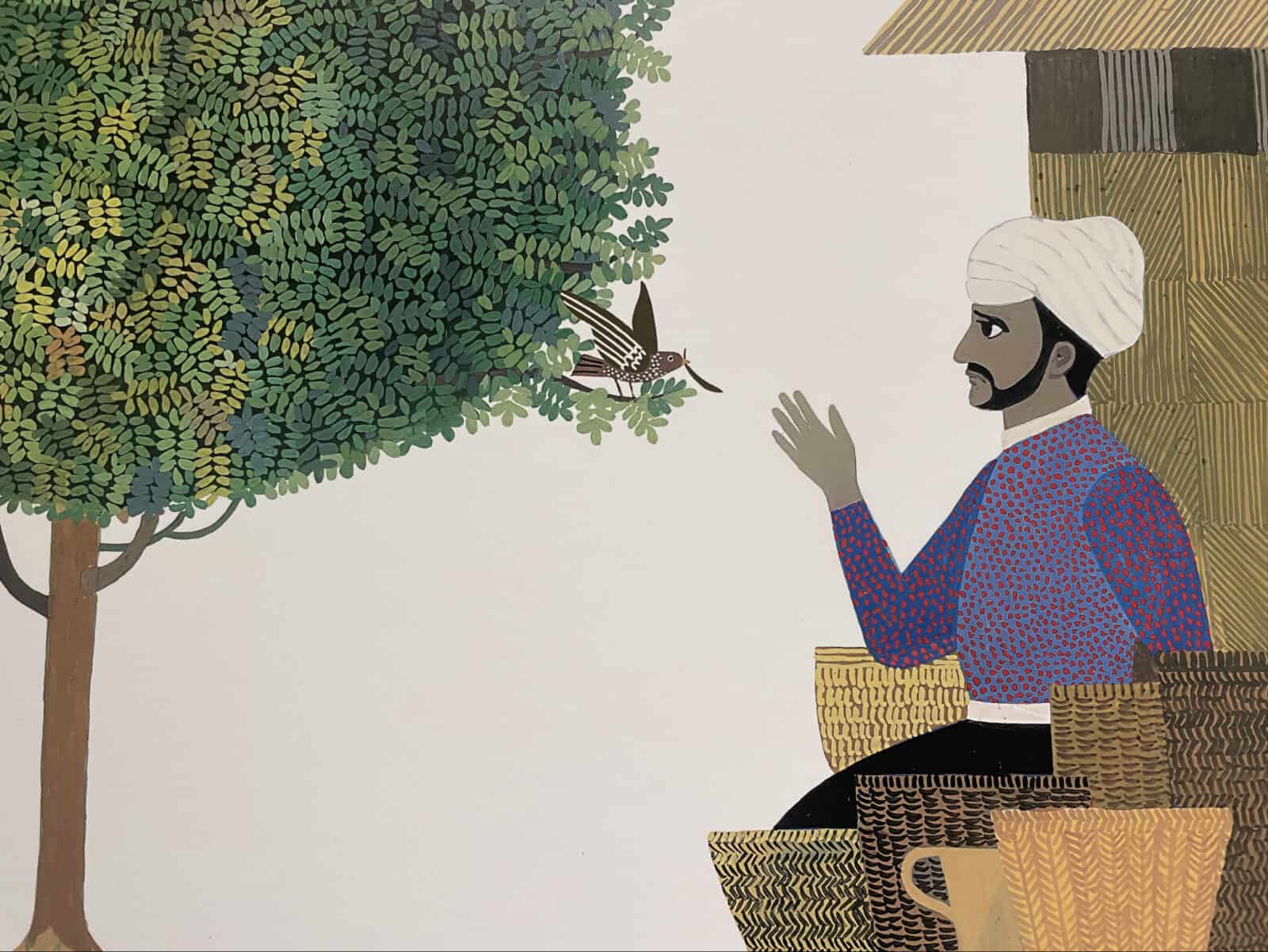

A bird flies toward a man in a turban who sits surrounded by baskets in Leo Lionni's Tico and the golden wings. Press image courtesy of the Norman Rockwell Museum

He set up an animation studio at India’s National Institute of Design in Ahmedabad — at a time when the NID welcomed visiting artists and teachers from John Cage to Louis Kahn, Merce Cunningham, Alexander Calder, Charles and Ray Eames and more.

He was never afraid to speak, Annie said, though he was gentle and humorous. He did not seek conflict, … but he had a strong sense of the kinds of actions that could build or break a community or a relationship, and he shared his ideas, personally and professionally and publicly.

“In practical and moral terms,” he says in the show, “you must be responsible for every line you draw, for every decision you make.”

“One of the most important things in life,” Marcus agreed, “is to be able to ask ‘what if,’ to be able to think about our lives and the world.”