People have seen whales and named them for more than 3,000 years — myths, sea serpents, leviathans. In Swedish and Danish, hval means rolling, arching in the water … professors Jeffrey Israel and Edan Dekel mull over Herman Melville’s etymologies, sitting together in Israel’s office at Williams College on a raw winter morning.

Moby-Dick opens with the names of whales in many languages, they explain, from Spanish to Fijan and Sie, the language of Nelocompne in the South Pacific, though he seems not to have known the real words, pahua or palaoa.

Last fall, on Rosh Hashanah, Israel and Dekel began reading Moby-Dick together, one page a day. They have found the experience transformative, they said, to read a book like this, taking time day by day and sentence by sentence — diving in, moving slowly and talking with each other as they go.

“… It starts the day with an excitement,” Dekel said. “What will it contain, what will it make me feel, how will it influence the day’s thoughts and conversations …”

‘It starts the day with an excitement. What will it contain, what will it make me feel, how will it influence the day’s thoughts and conversations …’ — Professor Edan Dekel

They are drawing on a Jewish practice called Daf Yomi, he explained, Hebrew for page of the day.

Israel is an associate professor and chair of the religion department, and Dekel is a professor of ancient languages and chair of the Jewish studies program. For more than 10 years, they have shared interests and projects in their teaching and intellectual lives

They often teach their students this way, they said, to focus on a short passage, and come with their own ideas and experiences and selves, and go where their minds take them. They draw on a Jewish art of interpretation, to engage intensely with the words, with a sense of curiosity as wide as the human mind.

A sperm whale's tale lifts in the sun as the whale dives. Public domain photo by Bernard Spragg of New Zealand

Daf Yomi as a contemporary form began hundred years ago. In 1923, Dekel explained, the First Jewish World Congress in Vienna launched a global project to study the Talmud (the central text of Rabbinic Judaism).

Jews in many countries began to read together, starting on the same day, at a page a day. At that speed, he said, the full cycle takes seven and a half years to cover the Babylonian Talmud’s more than 2,700 pages.

“It’s a way to engage with a text that seems bigger than all of us,” he said.

‘It’s a way to engage with a text that seems bigger than all of us.’

And the reading is still going on, Israel said. Each time the cycle comes to an end (with celebrations involving thousands of people), the reading begins again. By now, in the middle of the 14th, the movement has grown into digital space and around the world.

In that spirit, he and Dekel have begun began their own exploration of Moby-Dick, for their own pleasure — embodied, analog and rooted here, in the hills where they live.

For Israel, Melville’s classic is a book he had read passages from in classes years ago and meant for years to know better, and a path to explore unconscious elements in his own mind.

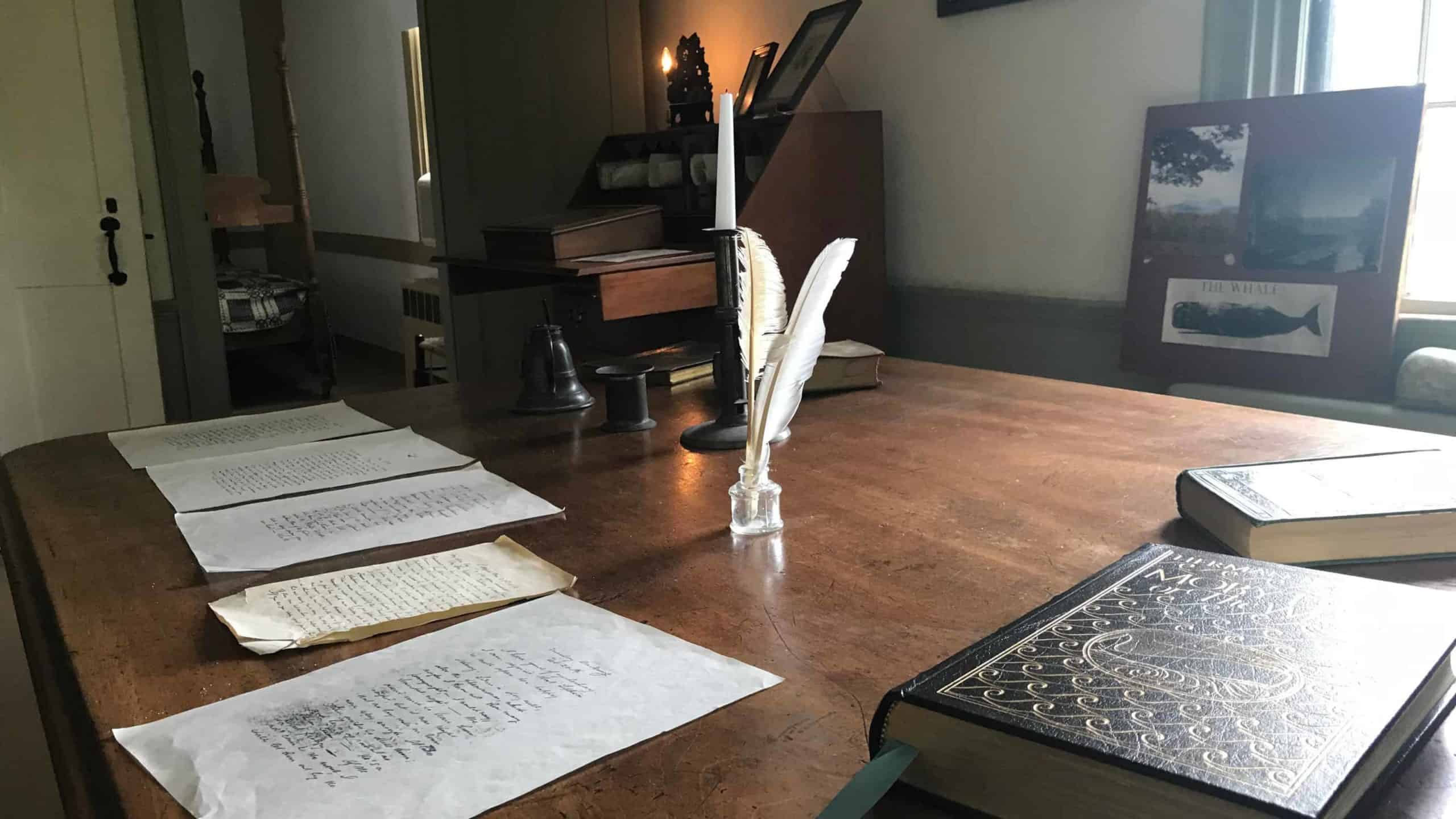

Herman Melville wrote Moby-Dick at his desk at Arrowhead in Pittsfield.

“For me it has a newness,” he said, “a possibility of surprise. And yet part of the reason I come to it, through other work of mine … it becomes an imminent cultural force in my imagination that I hadn’t explored.”

For Dekel, it has been a seminal work, one he has read and studied before, though he had not returned to it for a stretch of years.

“It’s one of the central works of art in my own life,” he said. “The first time I read it … it was the book that made me think I could live a life of studying literature.”

In September they launched into their new experiment with excitement. They printed out the pages with wide margins for their own thoughts, and each morning now they turn to a new page.

‘For me it has a newness, a possibility of surprise. And yet part of the reason I come to it, through other work of mine … it becomes an imminent cultural force in my imagination that I hadn’t explored.’ — Professor Jeffrey Israel

They have found the experience enlightening, they said, taking the time to immerse in Melville’s ideas and their own.

“I can’t believe now that I ever read any other way,” Dekel said. “It can feel almost too fast even at this pace.”

They are not necessarily looking for resonances with the Torah, Israel emphasizes. They may consider Ralph Waldo Emerson, modern psychology, current events. He sees Moby-Dick as a central American story. Melville was writing in 1850, on the eve of the Civil War, saw themes in his world that touch them nearly today.

A sperm whale's back and dorsal fin gleam in the sun as the whale dives. Public domain photo by Bernard Spragg of New Zealand

At the same time, Melville himself calls clearly in some ways to Jewish traditions. Almost the first word in the book is in Hebrew — or what Melville believed to be Hebrew.

Although the first chapter opens with the well-known assertion, ’Call me Ishmael,’ those words are not the first. Melville begins with a long prologue — 30 days long in Dekel and Israel’s measure. And his real first word is ‘etymology.’

He gives a word for whale in Hebrew letters, Dekel said — except that Melville did not know Hebrew, and the word Melville gives does not actually exist. The grouping of letters could mean grace or catching the eye — behold.

‘We’re doing this for its intrinsic goodness, for the insight into the world and ourselves, for conversations born of friendship.’

It’s the kind of opening people skip over without thinking about it, Israel said. And he has found that immersing in them over time has informed all of his reading. Melville opens his saga with a gathering of myths and roots of language, from ancient Greek to the opening of Genesis.

And he calls to a power that recurs in the Torah, Dekel said, a power of naming — Call me Ishmael speaks strongly in a tradition where creation happens through naming, and a change in someone’s name signals a change in their relationship with the world, with their God, with the energy of creation and with themselves.

They revel in the freedom and pleasure of diving into the words, opening them out, walking behind the scenes. They are doing what they challenge their students to do, they said — come together. Think. Make.

“We’re doing this for its intrinsic goodness,” Dekel said, “for the insight into the world and ourselves, for conversations born of friendship.”

“Fun is important too,” Israel said, laughing. “That creativity and play is something we are deeply committed to drawing students into. It’s one of the great pleasures of being a human being — having an expressive, good human life.”