Two women are catching a few minutes in their gardens at the end of the day. They have small plots side by side in a city neighborhood, in a place like Brooklyn, on a street full of newcomers from many places.

One is weeding with her bare hands, and one is singing softly as she picks figs from a tree. They have grown a kind of friendship, giving each other tomato starts and gladiolus bulbs — handing them over the garden fence.

But Blume Lempel says quietly, their friendship never crossed their thresholds. One woman is Italian American with grown children, and one Jewish and young, and on this evening (some 60 years ago) she is remembering family she has lost in the Holocaust.

Lempel untangles their tense, tentative exchanges in a short story, as she writes in New York in the 1980s — in Yiddish. She writes about contemporary women feeling the rasp, and sometimes the release, of trying to connect across a cultural divide.

Yiddish fiction writer Blume Lempel rests against a white car in the sun by a lake in a historic photograph. Press photo courtesy of the Yiddish Book Center

And her voice sounds among thousands this week at the Yiddish Book Center as they open ‘Yiddish: A Global Culture’ — making them (in the words of the Boston Globe) the first comprehensive museum of modern Yiddish culture in the world.

After five years of renovation, the center has reopened with a massive new exhibit led by curator David Mazower — a project he began soon after he came to the center from the BBC in London.

He wants to present the cultural language of the Jewish diaspora with the energy of the Harlem Renaissance, he says, or swinging ‘60s London.

‘That’s how I see modern Yiddish culture’s big bang, its swaggering emergence onto the world stage …’ — curator David Mazower

“That’s how I see modern Yiddish culture’s big bang,” he writes in a reflection in the show’s introduction, “its swaggering emergence onto the world stage … its youthful bravado and counterculture defiance.”

In the dramatic changes of the last 50 to a hundred years, he says, Yiddish has become, in popular imagination, “something unrecognizable: dusty, archaic, dying.”

He sees and hears it very differently. For Mazower, Yiddish carries the voices of activists and protestors, journalists and artists, and they are alive in the opening today.

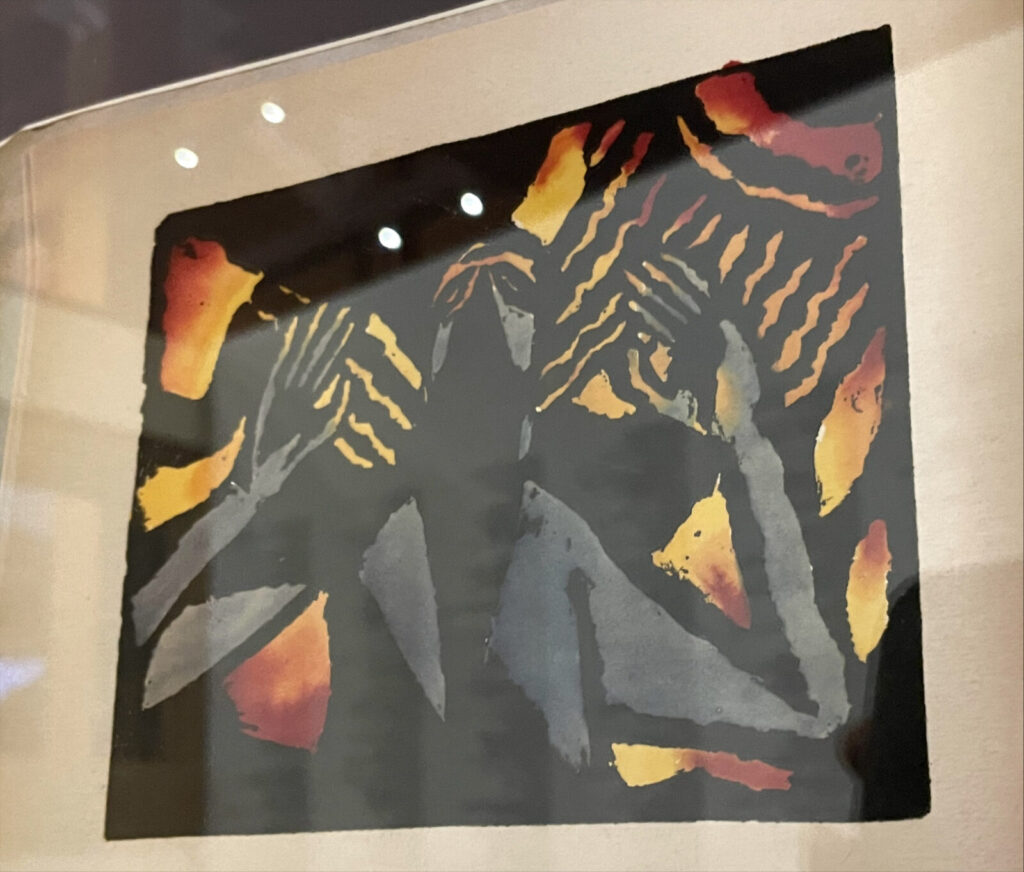

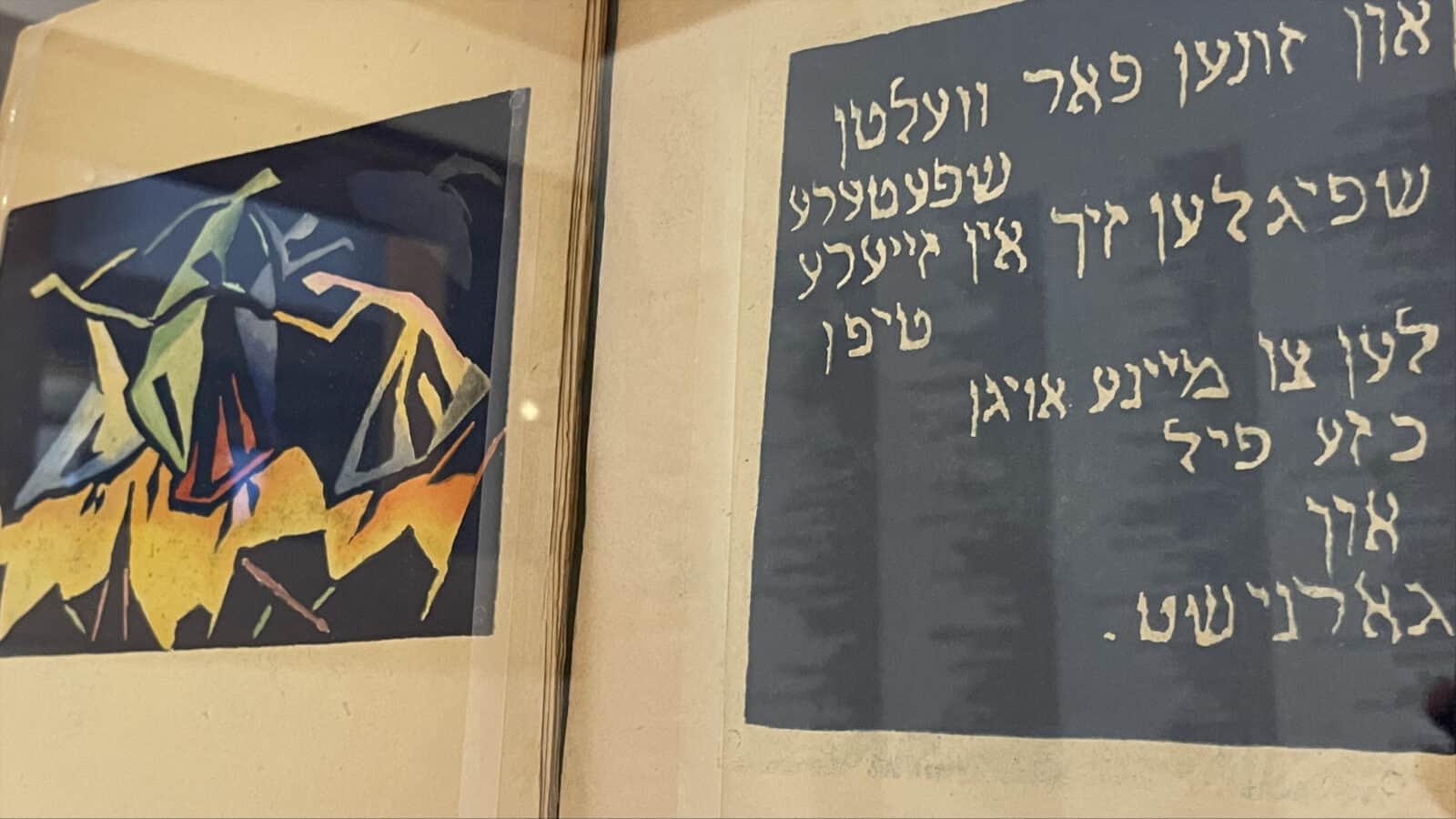

Esther Carp, Dina Matus and Ida Boymer published hand-colored books in Yiddish and German. Press photo courtesy of the Yiddish Book Center.

Musicians perform at the opening of A Global Culture. Press photo courtesy of the Yiddish Book Center in Amherst.

Yiddish is a language a thousand years old — and as cosmopolitan and immediate as the writers’ strike, debates over AI, protests for women’s rights, and avant garde theater. And it carries those debates into the 21st century

At the opening, a company of actors and musicians perform live in an afternoon of music curated by Frank London of the Klezmatics. A teasing tenor is singing, raising his hands and snapping his fingers with enthusiasm — he translates the refrain, once you’ve tasted it, you want it again.

Over piano and accordion and cornet, a young man dreams of coming to America, and another of the home he has had to leave. In a darkly comic debate, parents try to keep their daughter away from the unsavory ways they have been forced to make a living.

Caraid O'Brien performs at the opening of A Blobal Culture. Press photo courtesy of the Yiddish Book Center in Amherst.

Yiddish on the international stage

Caraid O’Brien performs in the Glorious Fabulous Incandescent World of Yiddish Theater co-created by some of the leading stars of 21st-century Yiddish theater, including Miss Mitzi Manna, Frank London, Miryem-Khaye Seigel, Lorin Sklamberg. and Mikhl Yashinsky

In a scene from Sholem Asch’s On the Road to Zion, a play she describes as a response to Anton Chekhov’s ‘The Seagull’ — and produced by internationally acclaimed the Russian actor Vera Komissarzhevskaya, who played the original Nina in Chekhov’s The Seagull — a woman walks in the hills in Poland, wrestling with her Polish and Jewish heritage.

They are performing as Yankl and Soreh in playwright Sholem Asch’s celebrated and controversial God of Vengeance — one of the most frequently revived plays of the modern Yiddish theatre, Mazower says, and a play he has paid close attention to, over the years, out of more than academic interest. Asch is his great grandfather.

The play has gone through a rapid kaleidoscope of responses since Asch wrote it in 1906, by Mazower’s description — ‘admired, translated, parodied, panned, banned, prosecuted, withdrawn, forgotten, revived, celebrated.’

Live on stage, Yiddish becomes the language of a modern drama in clear conversations with deep undertones as ironic as a Chekhov play — taking on themes of classism, exploitation, performative religion and real faith, two young women in love.

In novelist and curator Peter Manseau’s words, Global Yiddish Culture offers ‘an expression of (the language’s) vitality, its hunger for the new.’

A visitor looks at the last Yiddish linotype machine, on view at the opening of A Global Culture. Press photo courtesy of the Yiddish Book Center in Amherst.

As writers like Isaac Bashevis Singer formed a passionate group of New York intellectuals, the Yiddish press was covering labor and unions, women’s rights, Emma Goldman, immigration, rising rents and international conflicts.

Creative minds were reveling in musical theater, books in translation, fiction and nonfiction and science of the day, Margaret Sanger. The show rides a current of curiosity and hunger for knowledge, through the lower East Side and farther beyond.

In a black and white photograph, a book peddler comes to a small town in Eastern Europe on a summer day. He offers a kind of traveling lending library in a horse and cart — readers, many of them women and girls, would pay him a small amount to borrow a book for a day and return it, and then borrow another, for the few days he stayed with them.

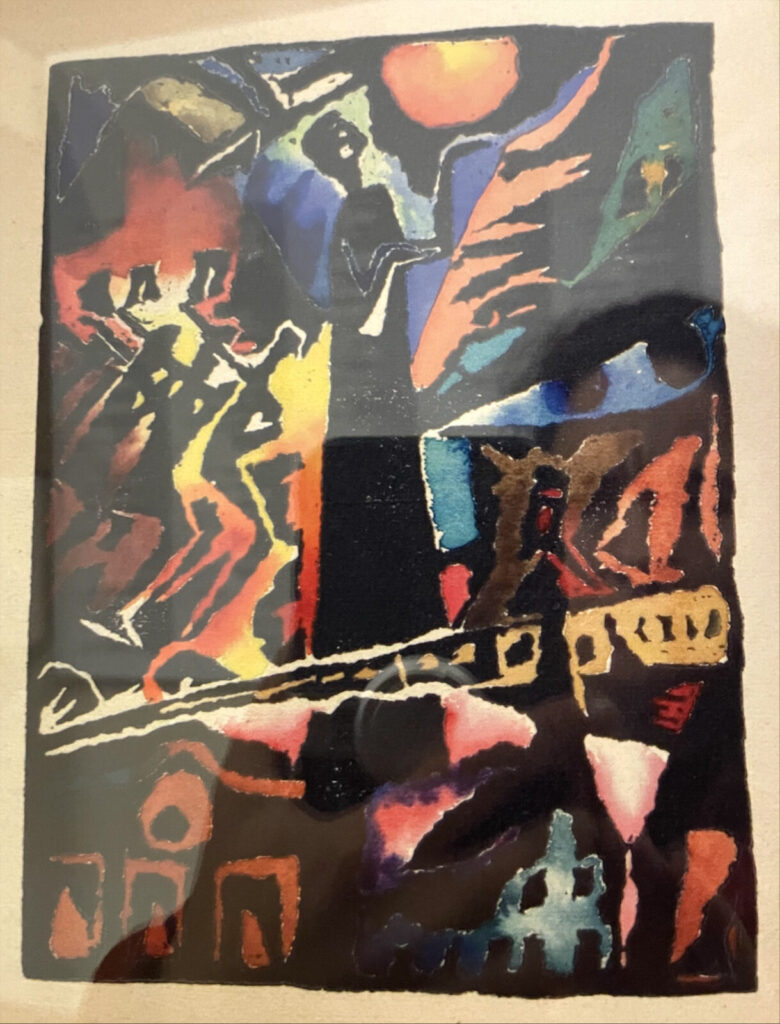

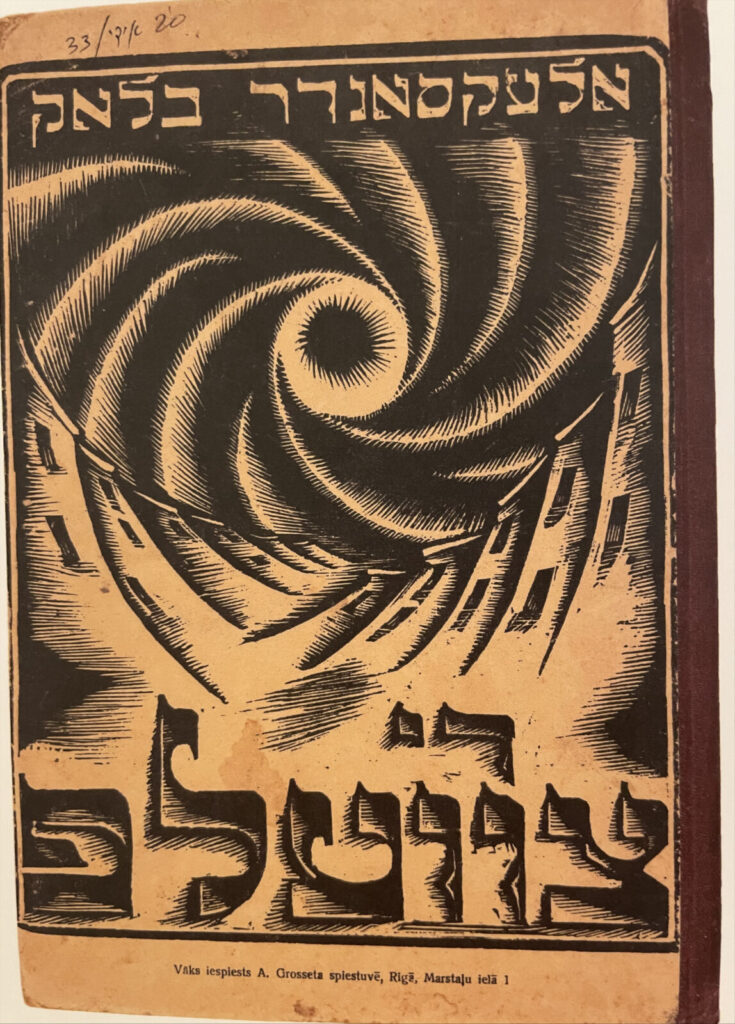

Aaron J. Goodelman’s sculpture Af Parad (On Parade) — Goodelman, born in what is now Moldova, taught at City College in New York and created work in his studio in the Sholem Aleichem house in the Bronx. Light and a cityscape seem to swirl on the cover of Aleksandr Blok’s Di tsvelf, published in Riga. Press photos courtesy of the Yiddish Book Center

Throughout the show, voices rise from many people who fought for the chance to learn. Lempel lived in the Ukraine, Galicia (northern Spain), Paris and New York, and she was writing at a time when “with rare exceptions, literary power and patronage within the Yiddish world was wielded by men,” a wall panel explains.

The show holds some of her letters with novelist and memoirist Chava Rosenfarb in Montreal. They supported each other, as Lempel wrote stories as immediate as three young hippies in mourning walking into an orthodox shul to play a folk song on guitar.

In Neighbors over the Fence, Mrs. Zagretti, the Italian American Catholic widow, walks for the first time into Betty’s house — the Jewish woman with the garden next to hers.

“We carry God in our hearts,” Betty tells her.

And she says: “I know. I often see you standing by the window. Only people who sense the closeness of God have such a look.”

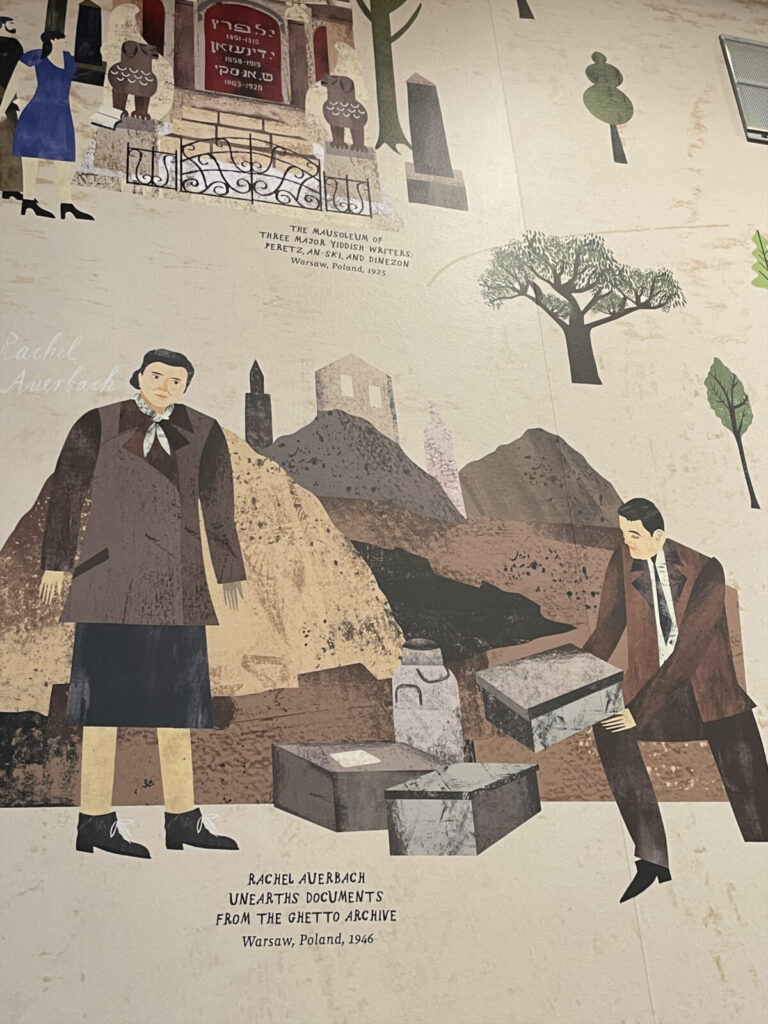

Esther Carp, Dina Matus and Ida Boymer published hand-colored books, and in a mural showing the reach of Yiddish cultyre, Rachel Auerbach unearths documents from the Ghetto archive.

Esther Carp, Dina Matus and Ida Boymer published hand-colored books in Yiddish and German. Press photo courtesy of the Yiddish Book Center

Students of the Mir Yeshiva escape the Holocaust and live in Shanghai, in China.