Ten thousand marchers come down Fifth Avenue. They walk silently to the sound of a steady drum-beat. At the front, children six years old carry banners: Give me a chance to live. Treat us so that we may love our country.

Ten thousand Black American men, women and children walked silently through midtown. They were standing together after a widespread riot in St. Louis, after police shootings, fires, buildings looted and families forced out of their homes.

It could have happened last night. But the silent protest stepped off Saturday, July 28, 1917.

James Weldon Johnson described the protest in his memoir, Along This Way, as he helped to plan it. In his lifetime he was an internationally known writer and politician, with influence from the Harlem Renaissance to the U.S. Congress, and like his old friend W.E.B. DuBois he knew the Berkshires well.

James Weldon Johnson was an internationally known writer and politician, with influence from the Harlem Renaissance to the U.S. Congress, and like his old friend W.E.B. DuBois he knew the Berkshires well.

He and his wife, Grace Elizabeth Nail Johnson, spent summers in Great Barrington. On summer weekends they would come up from Harlem to a white clapboard house with a stone chimney, and Weldon would write in a cabin in the woods. And now a group of contemporary artists have seen Alford Brook from his windows.

Daniel Hibbert, Selwyn Garraway, Susan Powers, Meclina Priestly and Cheryl Riley became the first season of a newly formed artist residency, said exhibitions program curator Margaret Cherin.

Seven years ago, Jill Rosenberg Jones and Rufus Jones moved into the Johnsons’ house on Alford Road and learned its history — and began a campaign to keep the Johnsons’ legacy alive. In 2016, they established the James Weldon Johnson Foundation, with Rufus Jones as the foundation’s president and Jill Rosenberg Jones as executor of Johnson’s literary estate.

And in summer 2017, the James Weldon Johnson Foundation and Bard College at Simon’s Rock invited five artists to live where he lived and work where he worked. The artists lived on campus in a red brick house for one to three weeks, and they could paint and sketch in college studio space or in Johnson’s own writing cabin.

Daniel Hibbert, Selwyn Garraway, Susan Powers, Meclina Priestly and Cheryl Riley created work as James Weldon Johnson artist fellow at Bard College at Simon's Rock. Press photo courtesy of the college

Cherin has curated a group show of the artists’ work in paintings and found objects, in February and March 2018 in the Hillman-Jackson Gallery. And in the spring, the artists gathered to talk about their time here.

For this fiirst year, Jill and Rufus invited artists they knew, Cherin said. Riley came up from her loft in Jersey City to cover a studio in 152 brilliantly colorful glyphs, symbols she evolved on pages of a 1957 encyclopedia.

Garraway drove back streets looking for local scenes to capture in watercolor — a gas station in Housatonic or a Victorian house that would have been newly painted not long before Johnson was born.

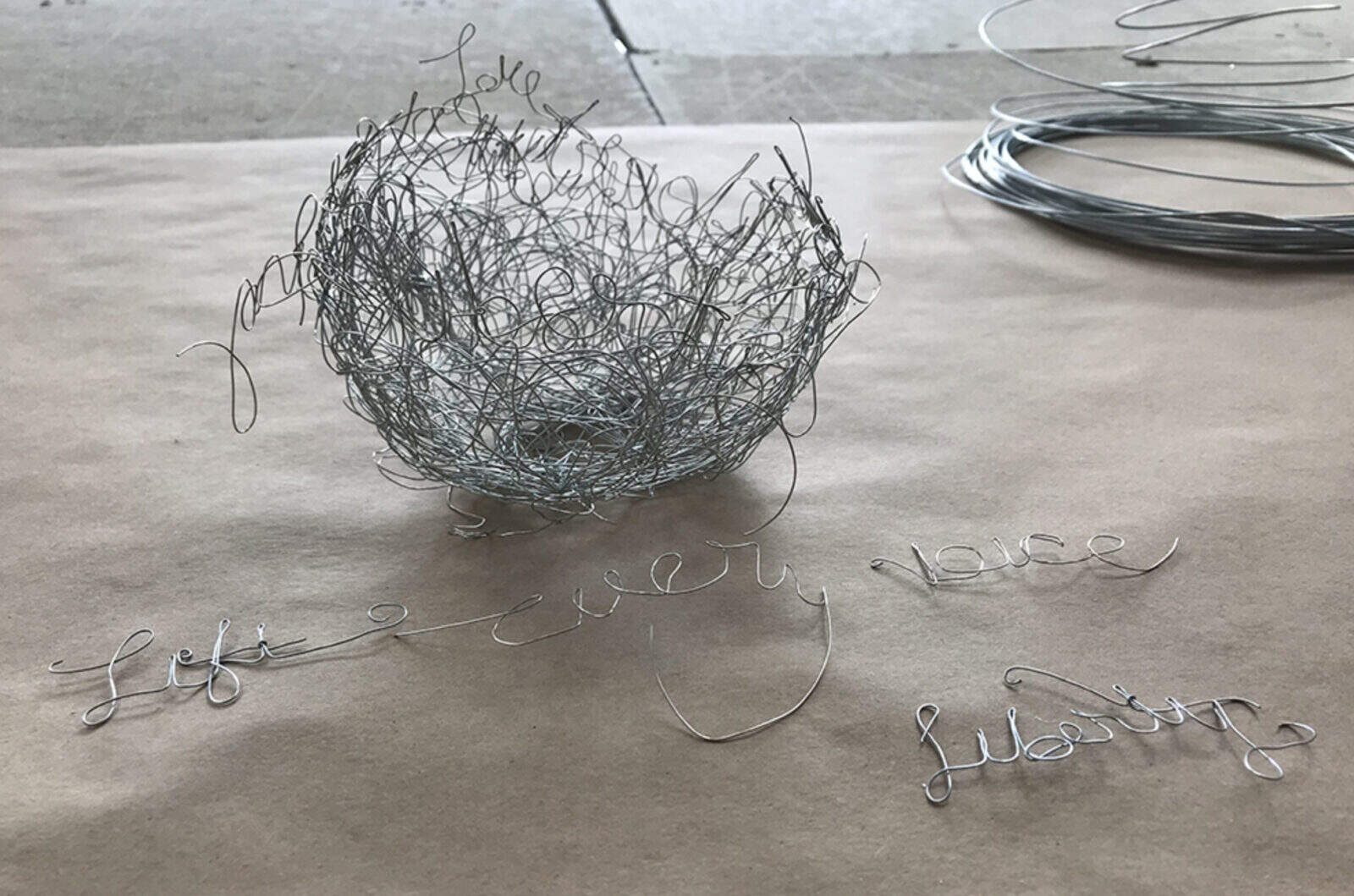

Priestly walked through the woods, gathering materials to build nests. She lives in Florida, where Johnson was born, and paints portraits with surfaces like light on still water. In 2016, she presented the James Weldon Johnson Foundation with a portrait of him in micrographic style — creating the image of his face with his own words.

Meclina Priestly seaves portraits in words and metalwork as a James Weldon Johnson artist fellow at Bard College at Simon's Rock. Press photo courtesy of the college

Johnson was a man of letters, an intellectual and a journalist, a novelist and a poet. He wrote wrote lyrics for Broadway musicals and gathered anthologies of Spirituals. He covered a lot of ground in his lifetime. He was a lawyer — the first black man admitted to the bar in Florida — a leader of the NAACP and a U.S. diplomat. He studied at Columbia and travelled the world — Paris and London, Venezuela, Honolulu, Kyoto.

Hibbert and Powers both live, as he did, in or near New York. She began painting scenes from the subway, as she thought about Johnson’s life. In his studio here, Hibbert has followed Weldon’s passion, deep intelligence and lifelong debates into the 21st century.

Daniel Hibbert and Susan Powers both live, as he did, in or near New York. She began painting scenes from the subway, as she thought about Johnson’s life. In his studio here, Hibbert has followed Weldon’s passion, deep intelligence and lifelong debates into the 21st century.

He created an image of balanced wooden blocks inspired by James Baldwin, Harlem-born novelist and activist, and the freedom of perspective Baldwin found in fighting for his people without joining major political or religious movements.

And two doors painted black and written over like a chalkboard draw on cultural references from rapper Jay-Z, are building a portal to a “self-sustaining black community of entrepreneurs and leaders” — a community Johnson worked to build all his life.

Sonya Clark, an internationally accaimed professor at Amherst College whose work has been exhibited in more than 350 museums and galleries in the Americas, Africa, Asia, Europe, and Australia, creates artwork inspired by the intimacy of braided hair, as a James Weldon Johnson artist fellow at Bard College at Simon's Rock. Press photo courtesy of the college

Johnson too created his own work out of the music people sang at work and in the streets and the familiar stories they made part of their lives.

In 1927, on a winter weekend after Christmas, he came here to write the last five poems in God’s Trombones. He found the thermometer there around 18 below zero, he writes in Along the Way, and he stayed two weeks to finish the book.

‘In the cool of the day —

God was walking

around in the garden of Eden …’ — James Weldon Johnson

It is a collection of poems inspired by the tradition of black American preachers, sermons he heard as a rich oral tradition.

“I remember in my boyhood sermons that were current, sermons that passed with only slight modifications from preacher to preacher,” he wrote, like the Valley of Dry bones, based on the vision of the prophet in Ezekiel, or a railway riff with saints on the line to heaven.

In his boyhood, in the 1870s, preachers were actors who could tune their voices. A preacher could move like a dancer and play tension like a chord. He could speak as low as the wind before the rain or crash and thunder. He could turn on humor and touch sadness and rage.

Weldon felt that power. A preacher stood at the center of the community. He gave people forced to this country from many parts of Africa “their first sense of unity and solidarity.” Sixty years later the tradition still existed.

“I heard only a few months ago in Harlem an up-to-date version of the Train sermon,” he said, “… The Black Diamond Expressway, running between here and hell and making thirteen stops and arriving in hell ahead of time.”

But he felt it becoming rare. And he wanted to fix it, to keep it current.

‘In the cool of the day —

God was walking

around in the garden of Eden …‘

He caught the idea on a cold night with a feeling almost of ecstasy, and he brought it here to the woods and the frozen brook to see it through.