Two men are holding each other in a hospital room. One of them is lying lean and tense in a hospital gown, and the other supports him to lift up. They sit together on the inadequate bed, facing an impossible diagnosis … a powerful image a musical first produced in 1998.

Tonight, neural pathways light up around them like leaves in dappled shade in Bill Finn’s A New Brain at Barrington Stage Company. He is a Tony Awardwinning composer with a long relationship with the company and a longer line of national honors, and Williamstown Theatre Festival has joined BSC this season in a play they present as a celebration of creativity. Intelligence and imagination form the set-up, the central theme — but the reality can often become darker and more complicated.

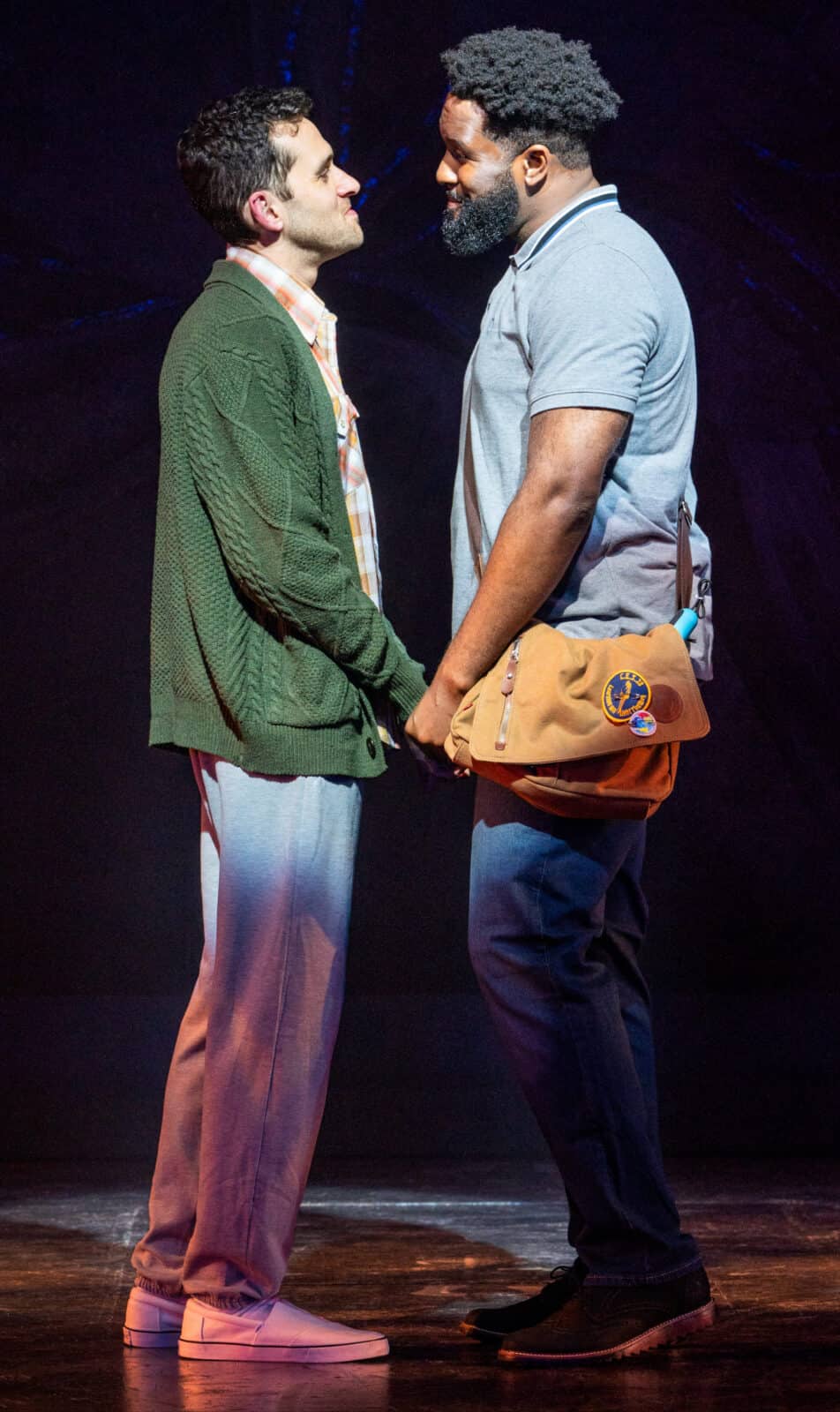

Darrell Purcell, Jr. and Adam Chanler-Berat appear as Roger and Gordon in A New Brain. Press photo courtesy of Barrington Stage Company

Gordon is a blocked creative artist, a composer who has lost touch with his music. And then he collapses through a literal mental block, a swollen blood vessel in his cerebral cortex.

Adam Chanler-Berat as Gordon and Darrell Purcell Jr. as his partner, Roger, carry the play in many ways, as illness tests their relationship, and they hold the light in a dark and confining time and place.

Purcell focuses power as Roger, as the caregiver, the one who has to hold warmth and strength for two while his partner is dealing with severe trauma. Chanler-Berat is facing the real possibility of losing all sense of himself, and he gives compelling indications that he has faced pain in the past, and he still struggles to live with it.

The two bring a tense and nuanced clarity to moments between them, and a depth of love and understanding and laughter, often without words — in one scene that lingers in the mind long after, Gordon has recently woken from an unexpected collapse, angry and terrified, holding on to Roger as a lifeline even as he is telling Roger to leave him.

Roger knows enough to understand that fear — to hear the trauma response and let it go, to hear the real need Gordon doesn’t have words for. Their interactions hold some of the strongest moments on stage — as Roger walks the streets in the dark, vulnerable on the night Gordon waits for emergency brain surgery, and later as Gordon turns to him in one quick, fierce musical phrase.

The whole of the cast are powerful performers dealing with high energy and skill, with some central challenges in the narratives they are given to work with. BSC has gathered an ensemble with vividly powerful voices and strong melody lines, and they often bring nuance to roles that can give them little scope. Many of the characters are written as stereotypes based in humiliation — and shame is a mental block in itself.

Darrell Purcell, Jr. and Adam Chanler-Berat, Mary Testa and Dorcas Leung laugh together in A New Brain. Press photo courtesy of Barrington Stage Company

Dorcas Leung especially holds a strong voice as Rhoda, Gordon’s agent and close friend, caught between what she believes he needs to do to launch his career and what she increasingly knows he needs as a man.

The play gives us this central question clearly and explicitly — what does Gordon need? How does a creative mind unblock? Any writer and artist will have more than empathy for this theme, and Finn has made a creative block a real, tangible challenge. It matters. Life-and-death.

But to open a creative block, you have to understand the cause — you need to have some sense of what external or internal forces are jamming the stream. Creativity has an inverse relationship with anxiety or fear or anger. So you need honesty, some reckoning with past and present.

And I’m still waiting for that.

To open a creative block, you have to understand the cause — you need to have some sense of what external or internal forces are jamming the stream. Creativity has an inverse relationship with anxiety or fear or anger. So you need honesty, some reckoning with past and present.

Gordon tells us some of his far past — he tells us how and why his father left when he was a boy, in a forceful and fluid look back. Tally Sessions as the doctor steps into the father’s role powerful and unexpected in a dreamlike movement through space and time that shows the gripping power of pain, that an act in the past can leave marks in the present.

And Gordon recognizes some of the negative forces generated as he tries to get paid for doing the work he loves. He has been trying to write a song for a television producer who becomes the representation of all the negative, destructive, soul-killing voices that can undermine a creative mind — we don’t want your real ideas, you’ll never make a living being honest, you have to be commercial, you were never any good anyway …

Salome B Smith calls for change in A New Brain. Press photo courtesy of Barrington Stage Company

But those are tensions he already recognizes. To walk away from that bile and to heal, he needs to find confidence and love and power that can release creative energy. He needs to rediscover and grow his core inner confidence. He needs to know what he’s still afraid of … and that means confronting the challenges in his work and family and central relationships, with Roger, with his friends — and with his mother.

At the moments when Gordon has a choice, again and again, he repeats the pattern in the other direction.

In one of the most painful and awful, he turns away from Roger to write a song for the demented producer — he says if he has only one night left, he wants to write something he will be remembered for — but the song he is pressured to write is a lie. It isn’t his music, and it isn’t music he wants remembered. In the end he can’t make himself lie completely enough even to sell the producer on recording these words.

The music certainly gets one point across, in a chilling fingers-on-a-chalkboard cringe, when the cast are singing an upbeat just say yes to something you know, and they know, and Gordon knows, categorically and absolutely, that he needs to say no to.

He could learn from this choice. But at the pivot point of the action, when he seems to have a deep look into the working of his own mind — the producer is back, the mental block in solid form, moving Gordon like a puppet.

This is a definite evocation of the strength of a mental block, and of how hard it is for anyone to get past one, even with some self awareness and a loving partner and a life-or-death need driving them.

But letting the block drive is not untangling the block. It is the opposite. The block is in possession.

Gordon wakes again into this grip. And the action that follows holds far more doubt than resolution. One of the central acts in the play, a returning theme, underscores the fear and loss of creativity in an equally tangible form. Gordon’s mother throws away all of his books.

Adam Chanler-Berat and Darrell Purcell, Jr, hold hands smiling in A New Brain. Press photo courtesy of Barrington Stage Company

Mary Testa as Gordon’s mother comes on strongly, troubled and in pain, a powerful performance of a woman who has been hurt in ways she has not recovered from. And the clearest response she gives in this crisis is a destructive one. On the night when Gordon is waiting for surgery, she goes back to his apartment to clean, and she clears his shelves.

On this bleak night she reveals her rage at his father, who abandoned her and Gordon both, and the pressure she has put on Gordon, and her anger at him now, when she is afraid Gordon may leave her too.

It’s a skin-crawling move. In this context, it’s devastating. For a man searching for creativity, his books are a central part of his creative nerve center — they all of the conversations and voices and ideas he has gathered since college. And more than that, he and Roger have gathered them together. We will learn these are Roger’s books too, and Roger is the greatest healing and creative force in Gordon’s life.

Gordon’s mother — we never learn her name — is taking out her anger at her son, and at his illness, by destroying the visible center of his creativity. She is destroying the source of his confidence. She suggests strongly that she is afraid of the conversations that could bring them both closer to healing, and she has taught him to be afraid.

And she and Gordon never resolve this tension. They never talk openly in the present. She has one rare moment of gentleness on the night before his surgery, telling him to stay with Roger, to hold the person he loves while he can. And Gordon refuses to listen.

So she walks into his apartment alone in the dark, and that is essentially where the play leaves her. She has very little time on stage after that — she and Gordon have no time to deal with this deepened gulf between them.

The books themselves return briefly in a way that could give Gordon new chances to recover them, to reach out to other people, to open conversations with Roger and with Salome B. Smith as the woman in the park … but he has almost no time here either. He only has a knee-jerk reaction he doesn’t like, one that severs him from his books again and, as far as we know, for good.

He is honest enough to see and admit that. But the open question still is whether he will make a real difference. Smith underscores that need for us. She fills the theater with her voice as she proclaims All I want is change. She turns a punning one-liner into a powerful call for overhauling broken systems, an indictment of the forces that have brought pressure to bear on her.

And I want to believe in Gordon’s change. I want to believe in his playful advances, his brief moments of honesty, and in his turn toward Roger, in his newly awakened sense of commitment to the man he loves.

But I walk away disturbed because the basis for that change has never come into the story, not tonight where I can see it. The last song is a beautiful testament. I feel so much spring. I wish I could believe that rush would last.