‘Tell your parents you love them tonight,” he says with the humor of understated depth — as though he is not remembering the nights he worked in a machine shop under fear of discovery and death, to keep his family alive — the food left in payment by people who could not risk seeing him — the train car without water, the last day he saw his mother and father — the last time he touched them.

Broadway and Off-Broadway veteran Kenneth Tigar is speaking as Eddie Jaku. He comes on as a warm, friendly man, unassuming, with skill in rueful laughter, who can play the crowd and hold the room in his hands. And he is shaken to the bone by his past. He has taken a blast to the soul that many people did not survive. He came alive out of the Holocaust. And his family did not.

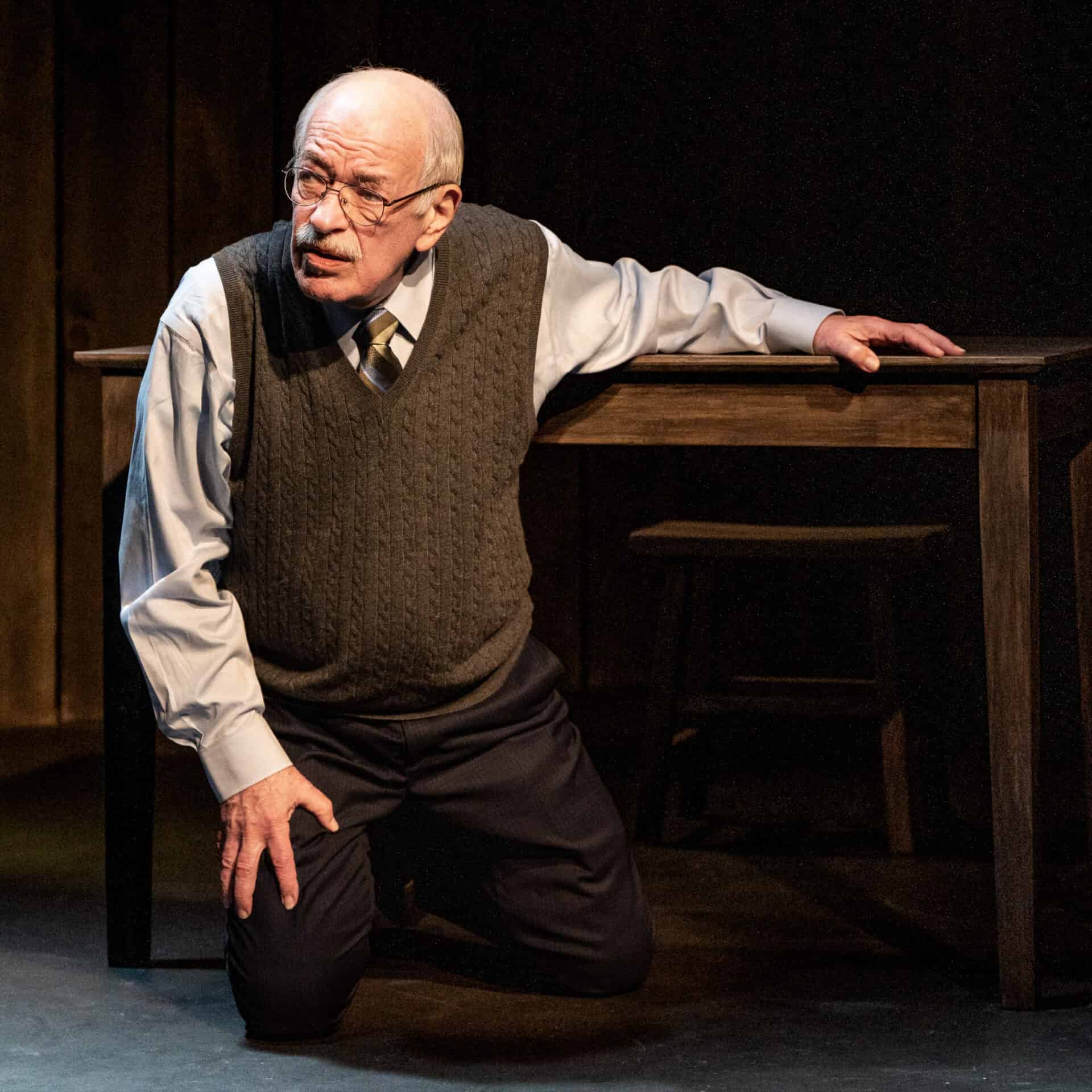

Kenneth Tigar stars in The Happiest Man on Earth, adapted from Eddie Jaku's memoir from World War II through a century. Press photo courtesy of Barrington Stage Company

“I have lived for a century,” Jaku writes in his memoir, “and I know what it is to stare evil in the face. I have seen the very worst in mankind, the horrors of the death camps, the Nazi efforts to exterminate my life and the lives of all my people.”

The play comes from his own words and lived experiences, adapted by playwright Mark St. Germain — and the world premiere opens Barrington Stage Company’s 2023 summer season, the first since Alan Paul has come in as the new artistic director, after company founder Julianne Boyd’s retirement last fall.

Jaku comes on speaking familiarly with the crowd, in a spare place lined in panels of slatted wood. In this stripped-down space, he can shift in time and space. In a breath, he can move from present to past. From the wall of a house to a train car … to a barrack. To a cell. From a daily life to a nightmare that is real.

‘I have lived for a century, and I know what it is to stare evil in the face.’ — Eddie Jaku

He begins gently. His family have asked him to talk at their synagog tomorrow about his past, and he has never found that easy, and so he is feeling his way. He remembers a night long ago when he tried to tell some of this story to friends, and his son, still a young boy, listened in from the hall, hardly understanding.

Jaku looks into his own childhood. He was born Abraham Salomon Jakubowicz, called Adi — only years later, in this country, he became ‘Eddie.’ As a boy he saw Leipzig with uncomplicated pride, a city of art, science, lion cubs at the zoo. Remembering his parents’ generosity, he has the room laughing.

My mother said, ‘you can’t keep bringing so many people home to dinner — they can’t fit around the table.’ My father said, ‘You are right, 200 percent.’ … The next day he came home with a bigger table.

But rising fascism shadows even these years. Jaku’s high school rejects him because he is Jewish, and he has to leave home to continue school and enroll with a name that is not his own.

Kenneth Tigar stars in The Happiest Man on Earth, adapted from Eddie Jaku's memoir from World War II through a century. Press photo courtesy of Barrington Stage Company

And then events catalyze and accelerate — a familiar world fragments in a night. Kristallnacht. Buchenwald. He comes home after graduation and finds himself arrested, beaten and locked in a cement room in a place with a name that means beech wood. A place that once held trees in the wind has become ugly, debilitating, dehumanizing.

The change comes through to us in stark flashes. Light glares through the bare boards and turns them into bars. Searchlights. Headlights on a road through the woods at night.

Jaku is experiencing each event as they come, without hindsight, and they may be as terrifying, even more terrifying, when he strips back the myth of the machine and shows the humans who caused these atrocities — the fear and anger, psychosis and fallibility.

We are standing with him in the early days and monts of the war, and though the fascist military dictatorship is ruthlessly organized, he shows places where the future is not inevitable. The rigid system has gaps, as it does when he finds a way to get through school as an engineer.

It does again when and his family to escape to Brussels. And they meet a bitter irony. Inside Germany, their lives are at risk because they are Jewish. Outside Germany, their lives are at risk because they are German. The Belgians, under German attack, fear all Germans as spies.

Kenneth Tigar stars in The Happiest Man on Earth, adapted from Eddie Jaku's memoir from World War II through a century. Press photo courtesy of Barrington Stage Company

So the play moves, with continuing force in the pacing and the paring away — of people in Jaku’s world, health, the physical substance of his body. He will share the limits of mental endurance, and the strength, the fragments of connection he holds onto through grinding, daily fear.

Auschwitz. He tries to convey that hell to people who have never been there, the physical pain, indignity, the meeting of souls that could keep someone’s soul alive a day longer even without words, and the details that make his experiences come clear to us and viscerally real — bitter cold hours on the factory floor, prisoners sleeping in a heap together for warmth enough to wake up in the morning, gallows humor, parodies skewering the German high command — the smell of a culvert, the sounds of radio, the popular music of an American army barrack in France.

Jaku makes the people and the time real, as Rabbi Rachel Barenblat said at the Yom HaShoah service this spring at Congregation Beth Israel. When we see Eddie Jaku, we see the people who lived through what he has lived through, and the people he has lost — not as blurred faces 80 years ago in a black and white photograph — as people, as alive and complex as we all are.

He will live for the people who can’t, he says — for the people who are gone. He will tell his story for them, and for the people who have come after them. He remembers his son listening as a boy. “He should never have to hide in a hallway to hear about my life.”

And he has the room murmuring along with him when he repeats a thought his father had told him as a boy. Family First. Family Second. Family Last. And we’re all family …