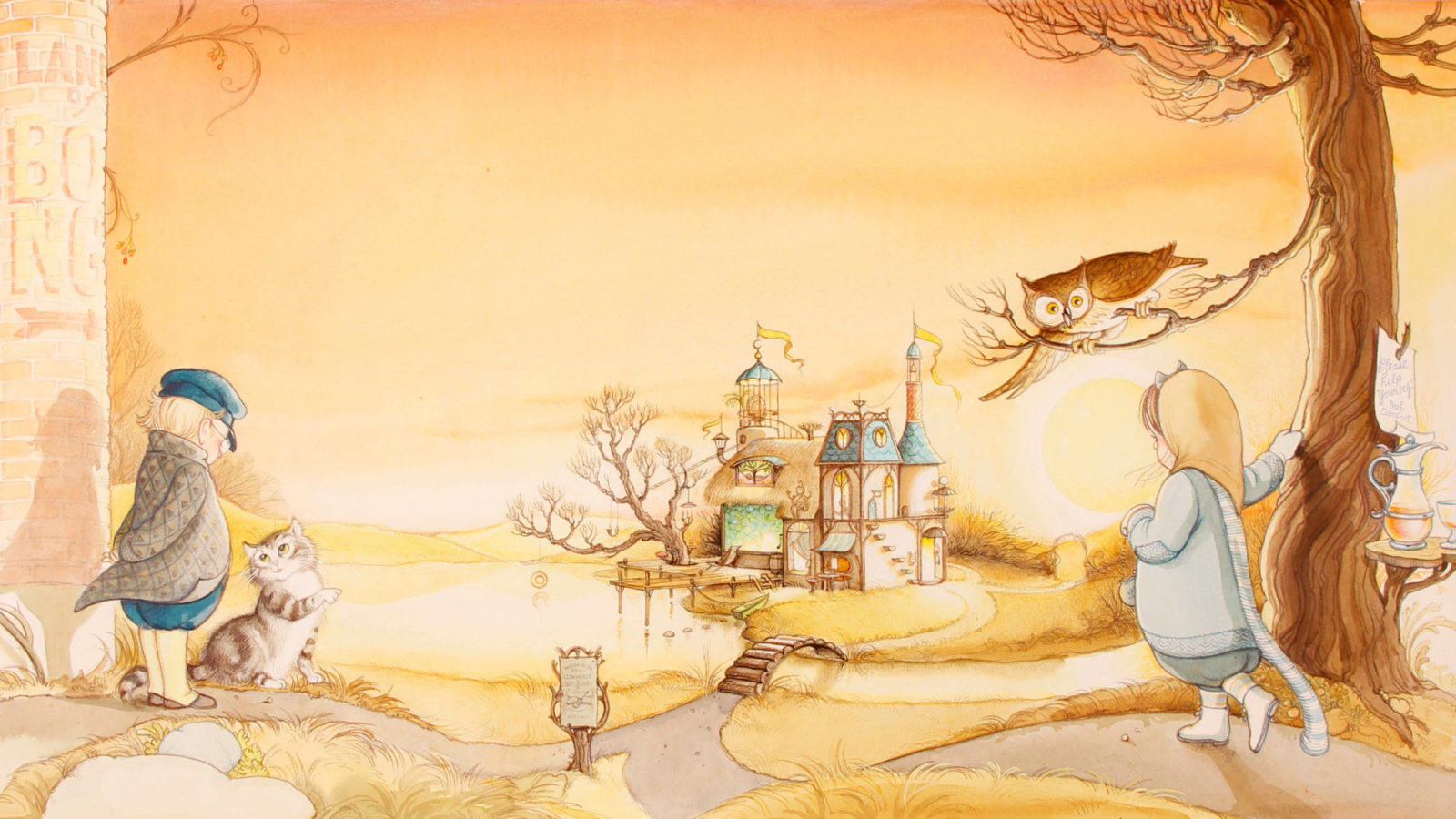

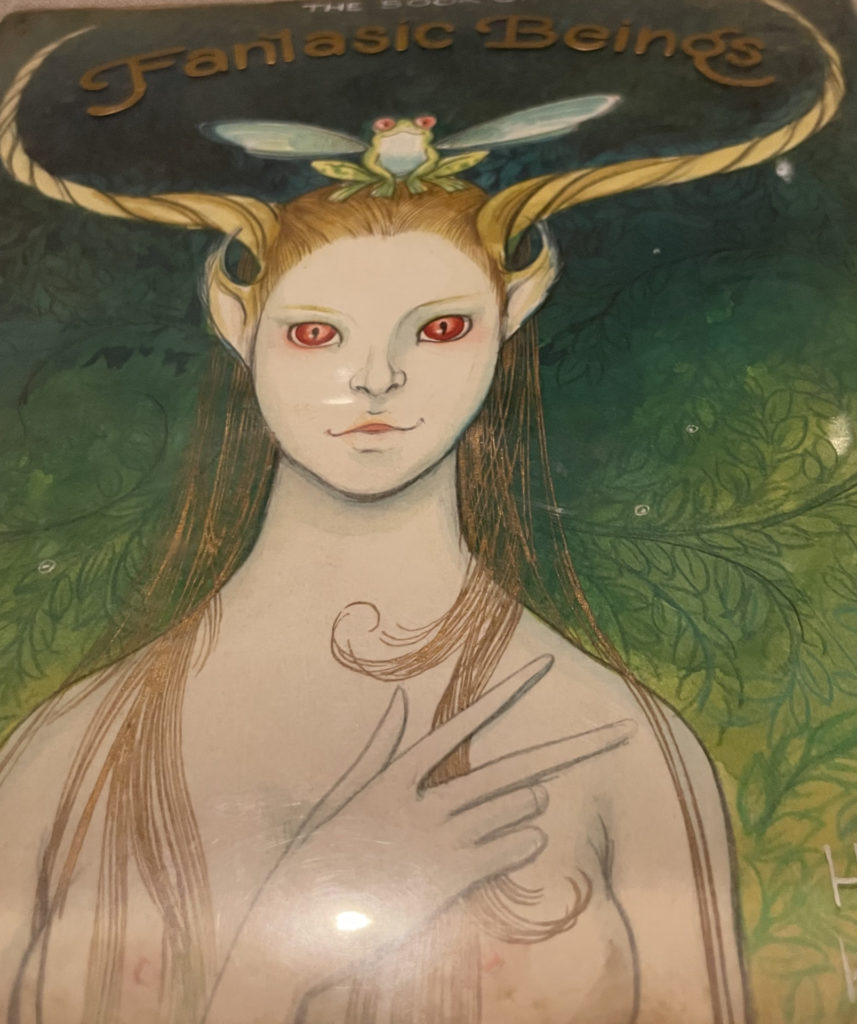

Two children follow an owl into golden evening light. A human-like creature with spiraling horns steps out of a dense wood. Regulars in prohibition-era speakeasy line the bar, looking at photographs of boxers in the ring.

Hilary Knight has explored New York as an artist for more than 70 years — and at 96, he still explores the city today in his drawings and paintings. Though he is often known as the illustrator of the Eloise books

he has wandered over a wild field.

The Norman Rockwell Museum follows his lifetime of curiosity and close observation, as exhibition curator Jesse Kowalski and Don Bacigalupi, the founding president of the Lucas Museum of Narrative Art, reveal in Eloise and More: The Life and Art of Hilary Knight.

A witch looks through the window, smiling at a child putting on a witch costume, in Hilary Knight's cover illustrations for Cricket Magazine in October 1983. Press image courtesy of the Norman Rockwell Museum

“As I was going through Hilary’s work,” Kowalski said, “I realized this man has a great career in so many different fields. And I thought he deserved a larger perspective.”

Knight grew up with surrounded by influences that had to do with books and people in the theater, and surrounded by artists. His mother, Katherine Sturges, illustrated children’s books and created designs for textiles, fashion and jewelry. His father, a flyer in World War I, illustrated fighter planes and drew a long-running comic strip about aviators.

He remembers their success when he was a boy, he said, in the 1920s.

“Both my mother and father were prominent illustrators,” he said, and illustrators were very important — they were like movie stars.”

‘Illustrators were very important (in the 1920s) — they were like movie stars.’ — Hilary Knight

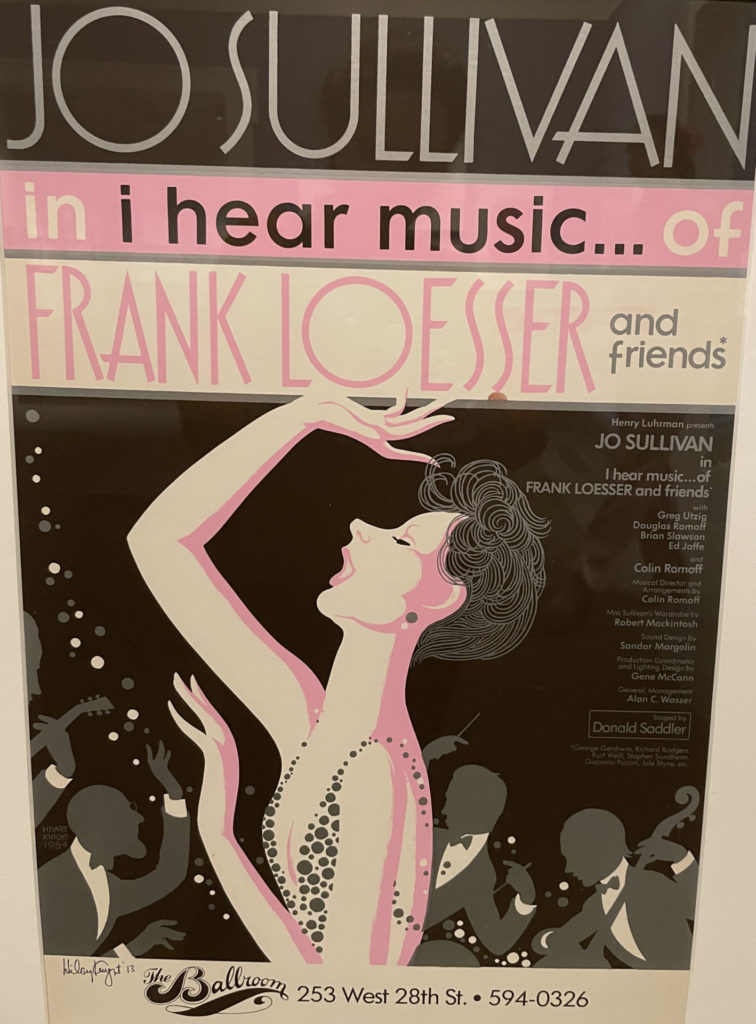

They taught him the importance of illustration, he said — he grew up in awe of the illustrators of that time, and as an adult he kept a pleasure in the style of that period, Art Deco and the 1920s and 1930s.

And he saw the field change in his parents’ lifetimes, he said. They were wildly successful as illustrators when he was a boy, and as photography came in, in the 1940s, photographs increasingly replaced illustration in magazines, books, posters for film and theater.

He still sees brilliant designers now, he said, but they are rare — he thinks of Jim MacMullen, who works regularly with the Lincoln Center, and Milton Glaser, who has created illustrations for theater. In his 1974 poster for The Wiz, a woman leans forward in silhouette, as though walking into the wind, and rainbow color fills in the vast blowing inkstrokes of her hair. In his images for Angels of America, a figure curls in shadow with light above them on multicolored wings.

“They were fantastically beautiful,” Knight said, “and yet he didn’t keep doing them.”

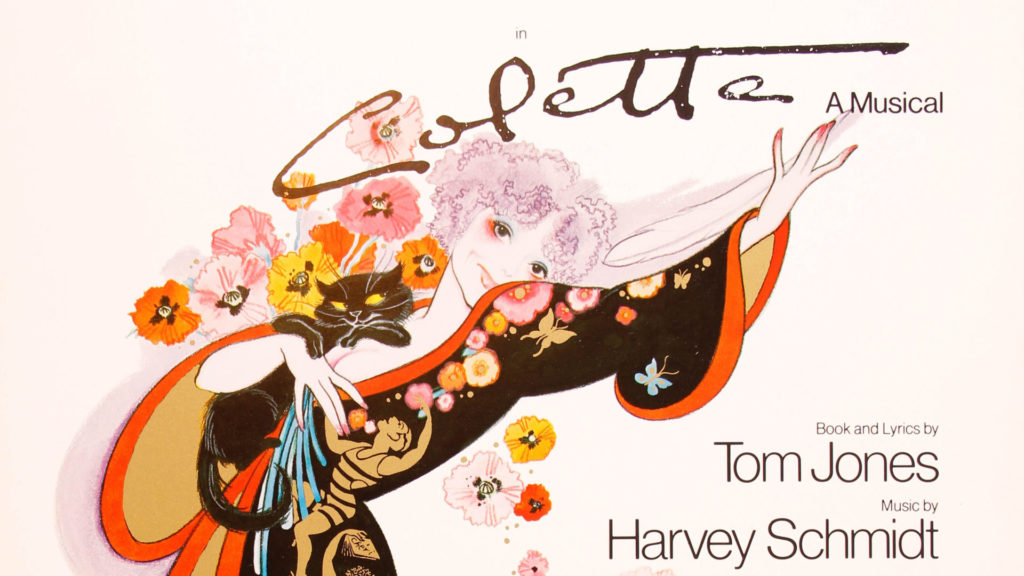

Knight himself has made a career across 70 years. The show explores his long association with Vanity Fair and magazines from Gourmet to Harper’s, and his lasting relationships in theater and design.

From a season in summerstock, he said, he went on to work with Broadway in the age of Julie Andrews, Angela Lansbury, Bernadette Peters. Lucille Ball as Auntie Mame shares the room here with Eartha Kitt, internationally acclaimed performer singer, musician, dancer with Katherine Dunham’s company.

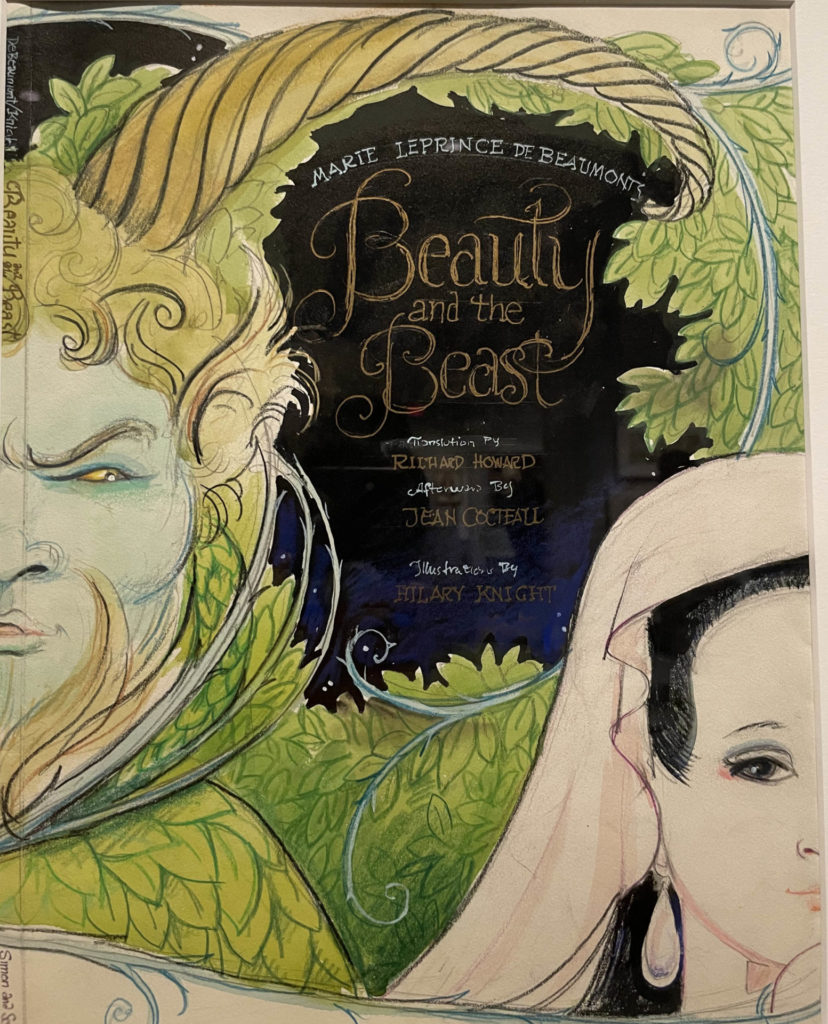

Beyond the stage, he explores imagined worlds in other media. While Eloise became popular around the world, Knight has gone on to illustrate more than 50 books — myths and fairy tales and the nonsense poems of Edward Lear. And performance and design continue to move him.

A woman smiles, showing the sheen on her dress of Pale Green Organza in Hilary Knight's fashion drawing. Press image courtesy of the Norman Rockwell Museum

Kowalski opens the retrospective with a wall-length sweep of fashion designs Knight created not for work but on his own, for the pleasure of it.

“We’ve had so many people today comment on the fashion drawings,” he said, “how lovely they are. And I think that art is beautiful.”

The show also explores many of Knight inspirations, beginning with the earliest — his parents. He remembers as a small boy reading a children’s book of poetry his mother illustrated.

She had studied art in Japan, Knght said, and through her hefound the illustrations of Edmund DuLac, a French artist who grew up in England and drew images for novels, children’s books and fairy tales — Jane Eyre, Shakespeare, the Arabian Nights, the Rubiyyat of Omar Khayyam, and even, in a local nod, Tanglewood Tales.

Many of them are stories with an Asian background, he said. Now he openly acknowledges their orientalism, but when he was a boy, they drew his interest to cultures and places new to him.

“Dulac’s Beauty and the Beast is an inspiration for me,” Knight said, “(though his is very different from mine) — my beast is not scary but … he has an intensity. And he’s sexy. That’s very important to me, in that story.”

A painting of an antelope in a rich forest of creatures and flowers appears among Hilary the works of artists who inspired him, including his mother, the artist Katherine Sturges. Press image courtesy of the Norman Rockwell Museum

His parents both had extensive libraries of books, he said. And the images they revealed to him could come back to him years later. The unlikely inspiration for one scene in Eloise came from a volume of Voltaire’s Candide illustrated by Rockwell Kent — a satire on a world at war. They were ghastly drawings, he said, and he and his brother were fascinated when they were boys.

As a deeper inspiration, he looked back to Ernest Shepard, who drew the illustrations for A.A. Milne’s stories, Winnie the Pooh.

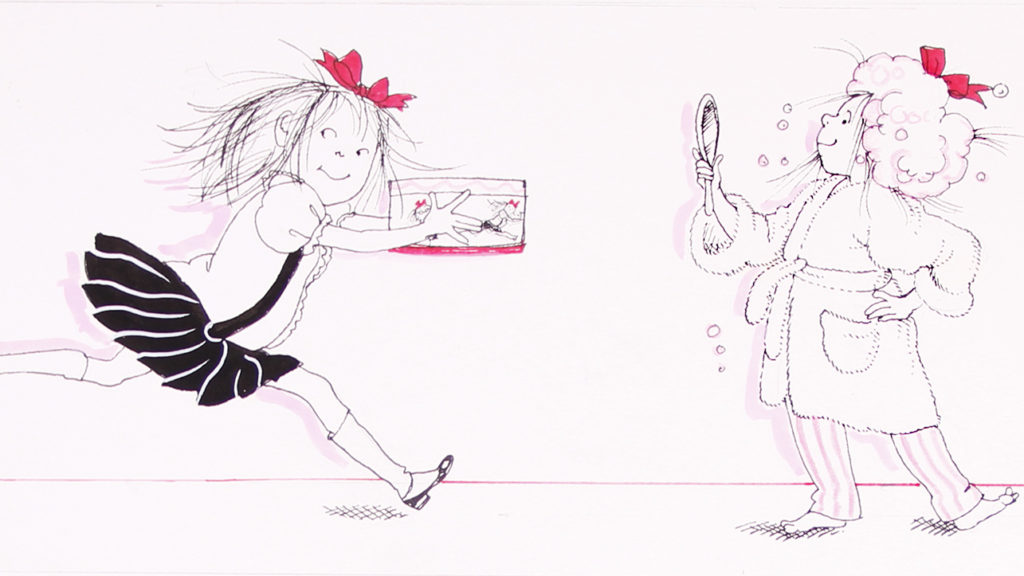

“They’re beautiful drawings,” Knight said, “small and simple, with a perfect minimum line, and full of action. That’s absolutely where Eloise comes in.

“They were probably the first illustrations I’d ever seen, because they were the first I’d ever been given, and so they were some of my first visual impressions as a child. And Piglet has a huge influence on Eloise, in his scampering and action — that’s a big part of Eloise, her mobility and nimbleness.”

He also recognizes one of his first teachers at the Art Students League in New York, Reginald Marsh. As an artist, Marsh was known for sketches of New York street life and cartoons and drawings in the New Yorker and for his emphasis on understanding the human body, inspired by artists like Michelangelo.

“He was an anatomy expert,” Knight said, “and I learned more from Marsh than from anyone, especialy about movement. He taught me how to make Eloise move.”

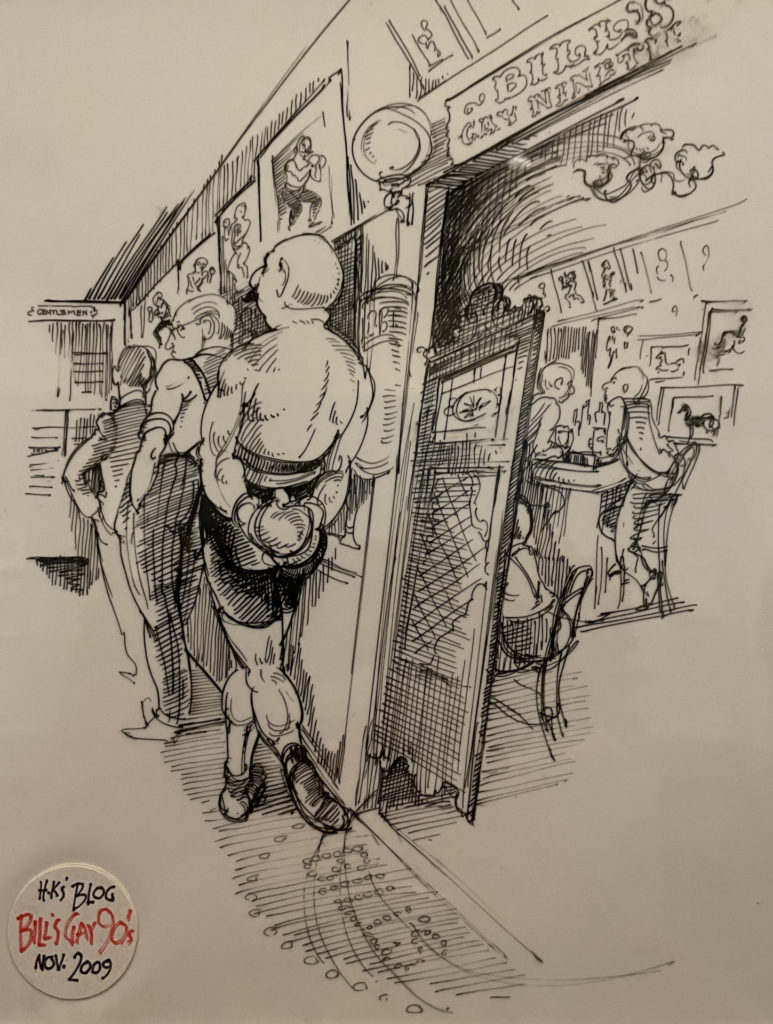

Hi father too taught him an appreciation for the beauty of movement. At art school in Chicago, Knight said, his father had known an artist named George Bellows who became famous for boxing paintings — huge, full of life and action famous boxers and prize fights.

“My father and I have a tremendous backstory of teachers,” he said.

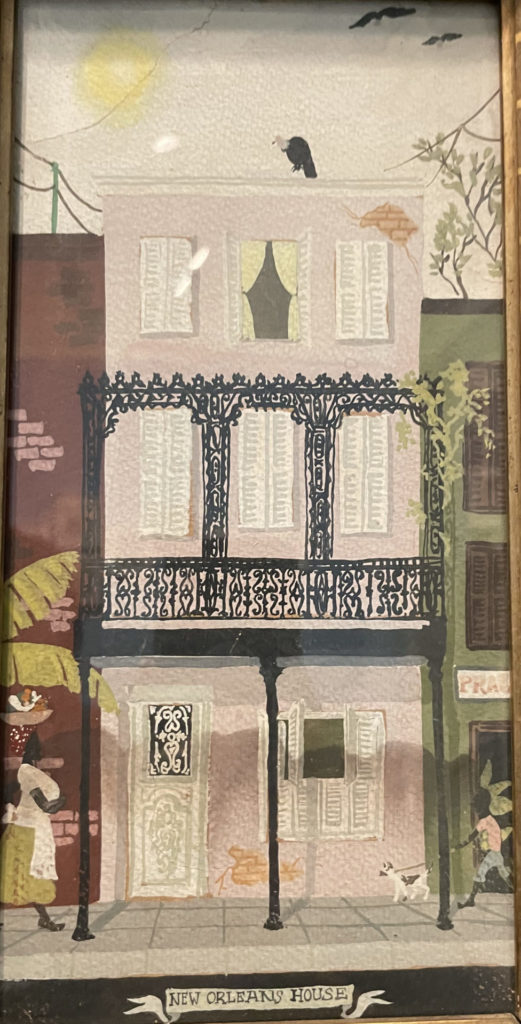

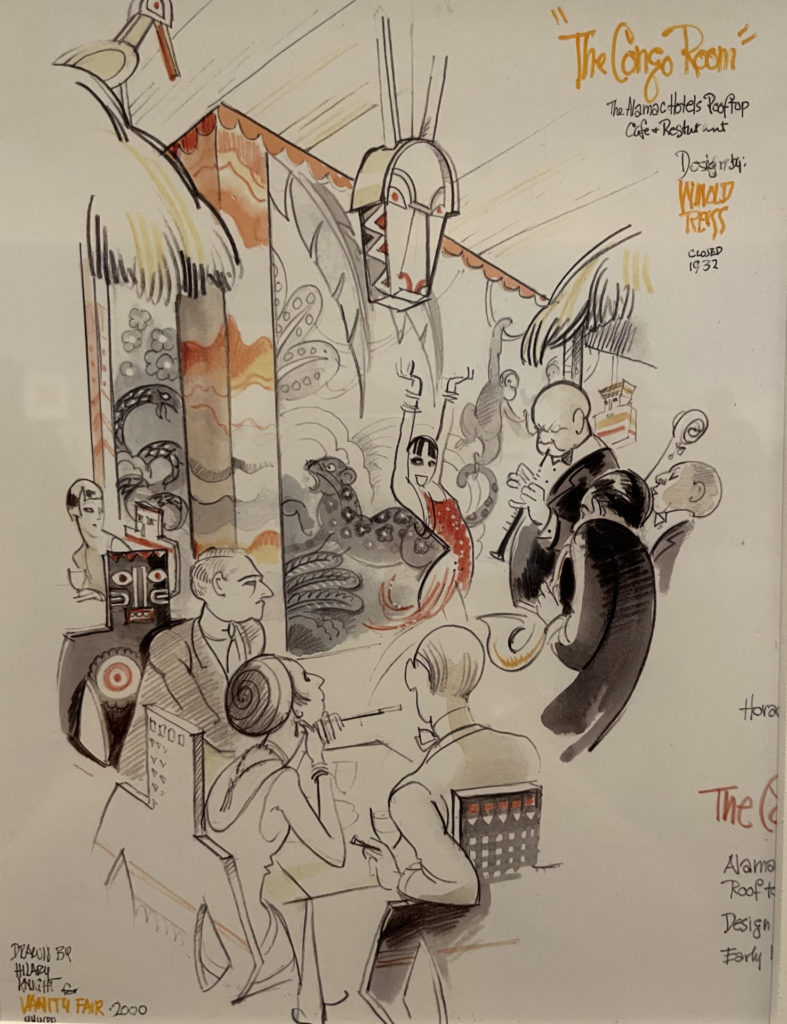

Knight may give a nod to Marsh in his own sketches. The Rockwell show includes illustrations from Hilary Knight’s sketchbook for Vanity Fair.

Musicians and dancers perform at a jazz-age nightclub, and regulars line up at Bill’s Gay Nineties, a bar in a townhouse on East 54th Street that had opened as a speakeasy and run for decades with an hommage to the 1890s. It is still open today, for a drink and dancing to live piano.

Art as a Cabaret

Hilary Knight recalls the energy of performers he has deeply admired — the Brazilian singer and dancer and Broadway actor Carmen Miranda, and Lena Horne, Tony and Grammy awardwinning acclaimed dancer, actor, singer, Civil Rights activist.

Like Kay Thompson, the author of Eloise, Horne made a career in film with MGM, beginning in the 1940s, an uphill challenge for a Black woman. She left Hollywood for nightclubs and Broadway and a national touring career as a musician, performing across the country (and even in the Berkshires — she gave a performance at Tanglewood in 1982.)

And Mei Lin-Fang, one of the popular Chinese actors of the 20th century, played Song Liling in David Henry Hwang’s Tony awardwinning play, M. Butterfly, in the character of a Chinese opera star, a man who lives as a woman. He learned of Mei Lin-Fang’s performances through his mother’s artwork and professional studies and found his work extraordinary.

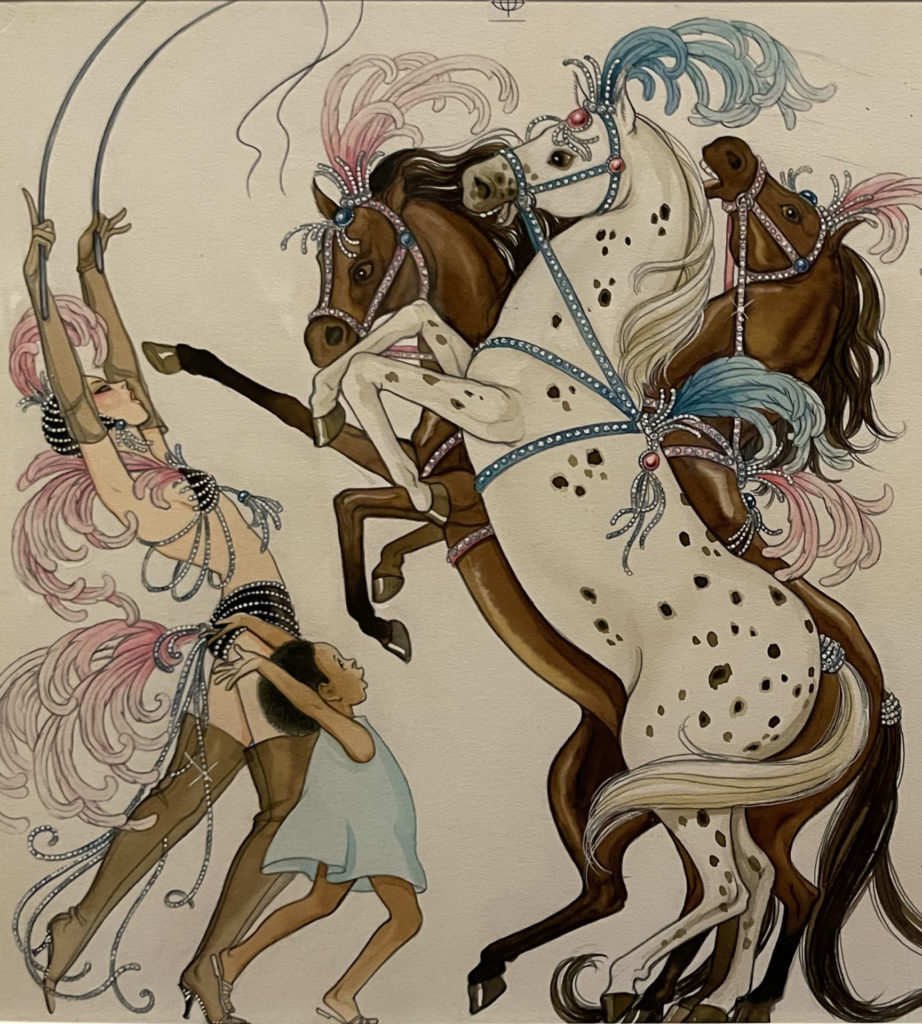

Many of Knight’s images release an energy in music and color and physical movement, from theater to Madison Square Garden, to a lifelong fascination with circus performers. He recalled drawings he has created for an imagined show, a high-end burlesque involving both men and women, with a globally diverse cast and music. None of those drawings appear in the Rockwell show, he said.

But two of his favorite drawings are here. One, he said, a cover for Cricket, the children’s magazine, comes a period when he became fascinated by the differences and fluidity between boys and girls.

In this drawing, he said, he drew inspiration from a photo of a Yemeni youth with black curls showing at the edge of a turban. He did not know their gender, and the person he drew and painted kneels by a spiraling mosaic and a round window with a twilight sky. They look lithe as a teenager and thoughtful, intent on a slender insect sitting lightly on one hand.

The second image comes from a collection of Charles Dickens stories, a little-known story about a boy with a fantasy about being captain of a ship, and in the image he stands balanced on the nose of a whale in a whirl of spume. And the force of it astonishes him still, generations later.

“That’s the absolute favorite,” he said. “When you look at something and can’t remember how you ever did it.”