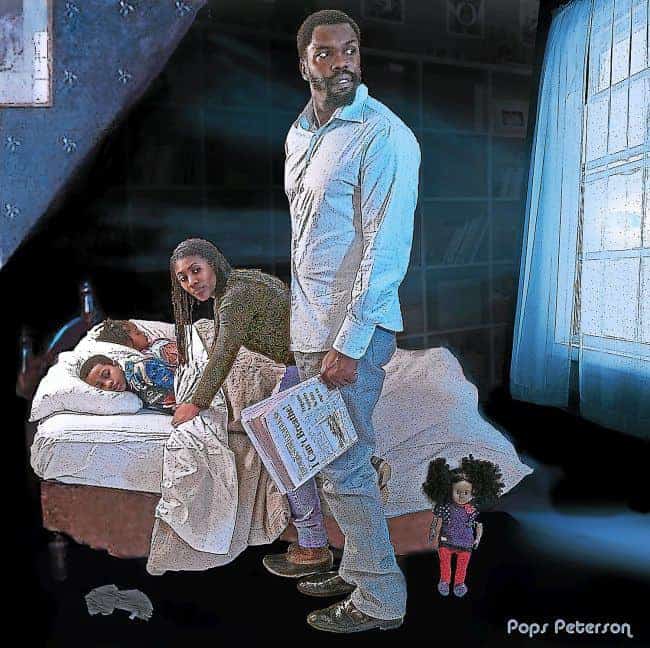

Roberta Dews and Eric Williams appear as a father and mother standing by a bed where two children sleep. She stands close to the boy and the girl, who lie quietly, and he looks out the window at the night.

Dews and Williams are local models setting a scene as people in the Berkshires and Vermont did decades ago for Norman Rockwell. Maurice “Pops” Peterson of Stockbridge has transformed Rockwell’s “Freedom from Fear” into a 21st-century image.

Maurice 'Pops' Peterson's 'Freedom from Fear' re-invents a Norman Rockwell painting in contemporary terms. Image courtesy of Maurice Peterson and the Norman Rockwell Museum

The father in Rockwell’s “Freedom from Fear” holds a folded newspaper with the headline half-hidden — “Bombings k— horror hit —.” The painting illustrated Franklin D. Roosevelt’s January 1941 address to Congress, made while German planes were dropping high explosives over London.

“It’s during the war,” Peterson said. “We have freedom from fear at home, here, but in some environments you wonder what’s going on outside.”

His work imagines parents today afraid for their children as they read the news. In Peterson’s newspaper, the headline reads: “I can’t breathe.”

His image hangs in a series re-imagining and transforming Norman Rockwell scenes with 21st-century people, 21st-century families, fashions, technology and friendships.

“I want to say what’s on my mind,” Peterson said. “So did Rockwell. He was on the edge. I’m not taking credit for this, but it means something. When ‘West Side Story’ comes out, does it ruin ‘Romeo and Juliet’?”

Peterson has had a long and varied creative career. He studied at the Pratt Institute and Columbia University and has written for publications like Andy Warhol’s Interview, Essence Magazine, The Village Voice and The New York Times. he has also written plays and screenplays, including “Homework” starring Joan Collins, and he wrote and produced the international television show “Models.”

In 2012, he launched an irreverent adult advice blog, “Come to Papa,” and found himself drawing illustrations for his blog posts. His drawings led to portraits, and then to a show in New York City, a commission to create artwork for the Center for Motivation and Change in New Marlborough and a show at the Lauren Clark Gallery in Great Barrington in 2014.

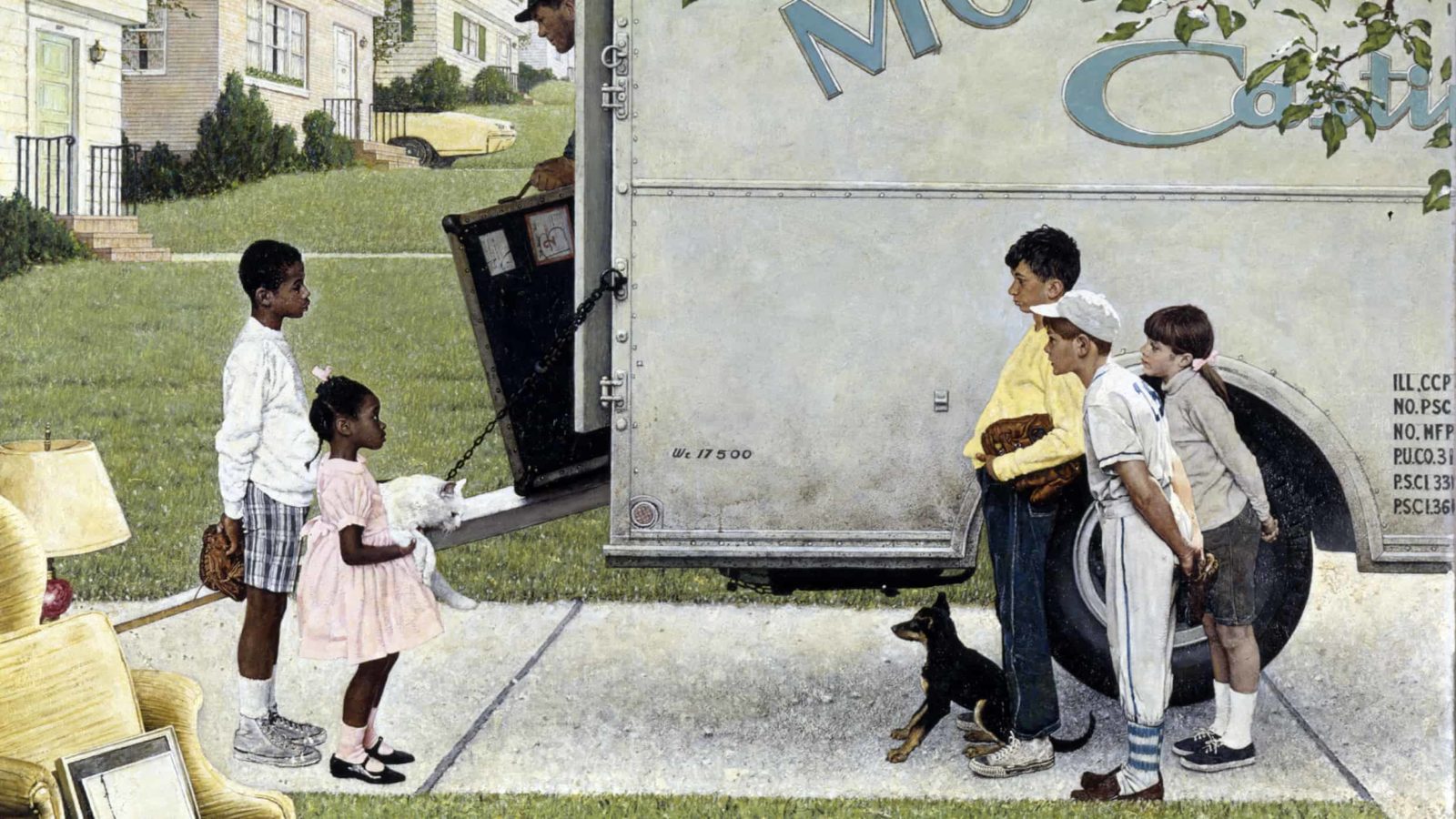

In 2015, his Rockwell series came to the Sohn Fine Art Gallery in Lenox. This show began with two women who have been together for 40 years, he said. He drew an illustration of them and thought “that looks like a Norman Rockwell painting.”

Norman Rockwell has always been a mystical figure in his life, he said. When he was a child, Rockwell was the first artist whose name he knew. Everyone read the Saturday Evening Post, in those days of three TV channels. Growing up in Queens, Peterson imagined himself in Rockwell’s country images.

“But the only time you saw someone black was in the controversial images,” he said.

He loves those images — Ruby Bridges, 6 years old, walking up the sidewalk behind two U.S. Marshals into an all-white school in New Orleans.

But he loves the daily images, too, the children getting a haircut, soldiers on leave, Main Street in a country town. In homage to Rockwell’s painting of Main Street, he has captured the blooming trees in the center of Great Barrington he knew would be taken out as the road is rebuilt. So when he looked at his image of two women in a loving and familiar relationship and thought of Rockwell’s images, he began to imagine how Rockwell might paint those images today.

He feels a connection to Rockwell, he said. Peterson and his husband, Mark Johnson, own Seven Salon Spa in Stockbridge. Their salon stands across the street from the house where Norman Rockwell lived and died. Peterson can look out from his office at Rockwell’s windows.

When Rockwell died, the building that houses the salon was a funeral parlor, and Rockwell’s family had his body brought there. Peterson has talked with a mortician who worked there at the time. He has felt a deepening connection with Rockwell’s spirit.

As he approached Rockwell’s images, he began with “Sailor on Leave,” a painting he owns. A boy in naval whites lies in a hammock with a beagle sprawled over his knee. His feet are bare and, in Peterson’s scene, his blue iPhone leans out of his shoes on the grass. In Rockwell’s original painting, the sailor had a pack of cigarettes.

To re-create this scene, Peterson took on Rockwell’s process. Rockwell worked with models and props, setting the scenes he wanted, photographing them and then drawing his paintings out of the photographs.

Finding a friend to model, a beagle, a hammock and a naval uniform led Peterson into a new kind of working. He found a reflector to intensify the sunlight. He set up his sailor, scruffy with stubble, in a pose that felt more sensual and up-to-date. And he used an iPhone and a computer to transform his photographed images into a painterly scene.

Peterson has always used the Berkshires as his palette, said gallery owner and photographer Cassandra Sohn. In this series, he has begun thinking about the place in new ways, building sets to tell stories.

He is not just rebuilding Rockwell’s images, he said — he is transforming them. And it takes time. His next image took a year in the planning.

From the sailor, Peterson moved on to a scene familiar to many locals and Rockwell fans: Rockwell’s “the Runaway” with a policeman and a young blond boy. Heidi Teutch, a Stockbridge police officer, volunteered to take part in Peterson’s new scene. She learned that she would need permission to have a photograph taken in her police uniform, Peterson said, and while she tried to get that permission, the Stockbridge fire department stepped in to help. So Teutch appears at the diner counter as a firefighter, facing Benjamin Gross, who is wearing her hat and sitting with a red backpack at his feet.

Peterson chose to re-create Rockwell’s image with a woman police officer and a child of color, he said, but more than that, he changed the feeling of the scene.

“In the original, you feel like the cop’s not going to let the kid get away with something,” he said. “Here, the chemistry between the woman and the child is warm. She gives him her cap to wear — she’s helping him.”

In another warm scene, a celebration inspired by Rockwell’s “Freedom from Want,” Peterson and Johnson stand as the host couple in a Thanksgiving Day image at the head of a long table of friends. The image comes from a real Thanksgiving dinner at the Stockbridge home of Jim Finnerty and Carol Murko, Peterson said.

Beside it, a more solemn image ties Rockwell to recent events. A collage of images shows the broken detritus of buildings after the riots in Fergusson, Mo. — and Ruby Bridges, the girl walking steadily into school in Rockwell’s “The Problem We all Live With,” walks here past the rubble. Her image helped Peterson express his grief.

“Everyone was talking about the riots and shootings, throwing blame,” he said, “and I thought, what about the kids? Their lives have been ruined, and they’re totally innocent.”

Bridges walked into the country’s first desegregated school 50 years ago. To think of her courage then, and to think of the young people in Fergusson today, to see some things that have not changed, moves Peterson strongly.

He has new work coming, Sohn said.

He has plans for a contemporary “Freedom of Religion,” he said, bringing together people of many faiths from the Berkshires.

“It’s part of a movement,” he said, “and people are rallying with me.”

He speaks of Rockwell’s work with deep respect, and of the support his own work has received with thanks.

“I’m joyous, satisfied,” he said. “I’m having a fantastic life right now.”

Learning Rockwell’s ways of telling stories, he will tell his own.

This story about Peterson’s work first ran in the Berkshire Eagle in March 2015, in my time as editor of Berkshires Week & Shires of Vermont magazine. My thanks to Vice President of News Kevin Moran.