A woman is singing from the spiral of a nautilus shell. Nina Simone’s voice comes low and clear, ‘Let me fly away with you, for my love is like the wind …’

She cuts clean across another voice who sees Adam alone in the cosmos, and another who suggests the universe is only coding. Around her a syrinx hangs in the air, a giant sea snail, and the smooth, mottled underside of a queen helmet, a sea urchin, the curved spines of spider conch and smooth torque of a triton’s trumpet or Pu shell …

Juan Antonio Olivares has gathered shells from the Gulf of Mexico and filled them with 21 voices, channels of sound, in Fermi Paradox III, named for the physicist who asked why, in vast universe 13.7 Billion years old, with many possible suns and planets, people on this one have not yet found more signs of life.

Outside, corn is tasseling, and tomato plants and summer squash are in bloom, as the Clark Art Institute opens Humane Ecology, and eight contemporary artists from across the country show their work indoors and outdoors.

At the entrance to the Lunder Center on Stone Hill, Professor Pallavi Sen has planted a garden. Nasturtiums nod through the gate, vivid orange and gold, and zinnias bloom by a bright woven trellis. The sun glints on glass shapes and ceramic tiles of sky-blue stars.

Deep color runs through the show from the hilltop to the museum’s front door. In the Pavilion and along the reflecting pool, Los Angeles artist Carolina Caycedo celebrates yarrow and crow berries, and women who care for the land and their communities.

Olivares’ shells hold messages about our search for kinship, he said, and longing and loneliness — Schopenhauer, Steven Hawking. Another voice starts to explain ways in physics that matter can hide from detection … but a woman is speaking in Spanish, and from Korakrit Arunanondchai’s film across the hall, a woman lifts up her voice, husky and determined, ‘wise men say only fools rush in, but I can’t help falling in love with you …’

An elder speaks respectfully to trees on a mountaintop against the sunset in Korakrit Arunanondchai's film Songs for the Dying at the Clark Art Institute.

“It’s a haunting work to move through,” said Robert Wiesenberger, curator of contemporary projects at the Clark, “ and hear the voices as they overlap, hear their fascination with intelligent life elsewhere — as (Western scientists) are now realizing how much intelligent life is here on earth, and how much we’re destroying or have destroyed.”

Christine Howard Sandoval also considers loss and preservation in her work. Beside a black and white photograph of a dam she offers an acknowledgement of all that can be lost when forces cut into ecosystems without thinking of the consequences. A poem by Deborah Miranda opens with love and sadness,

‘My father opens a map of California —

traces mountain ranges, rivers, county borders

like family bloodlines …’

Sandoval looks at forces that impose violently on the land, Wiesenberger said, dams and wildfires and flooding.

‘… when he comes to the valley

drowned by a displaced river …’

In this work, she studies flow and mechanisms that disrupt it, said artist Carolina Caycedo. Sandoval looks at systems for ‘management’ of nature and for social control and sees the same kinds of structures — rivers blocked, communities split.

She works with fire as a medium, Wiesenberger said, honoring the Native technology of controlled burning. Her people have used fire as a tool for forest stewardship for thousands of years.

“If we continued it today,” Wiesenberger said, “experts say we would have fewer wildfires.”

Sandoval is a member of the Chalon Nation of the Ohlone people from the Bay area near what is now San Fransisco, and while she now lives and works in Vancouver, she was born in Anaheim, Calif.

She has turned fire into a brush to make patterns on handmade paper imbued seeds and with beargrass used to weave baskets. This is a new body of work, Caycedo said. In the past she has made drawings in adobe on paper, like sculptural reliefs. These feel like weavings — in a way like Caycedo’s own Power to Nurture.

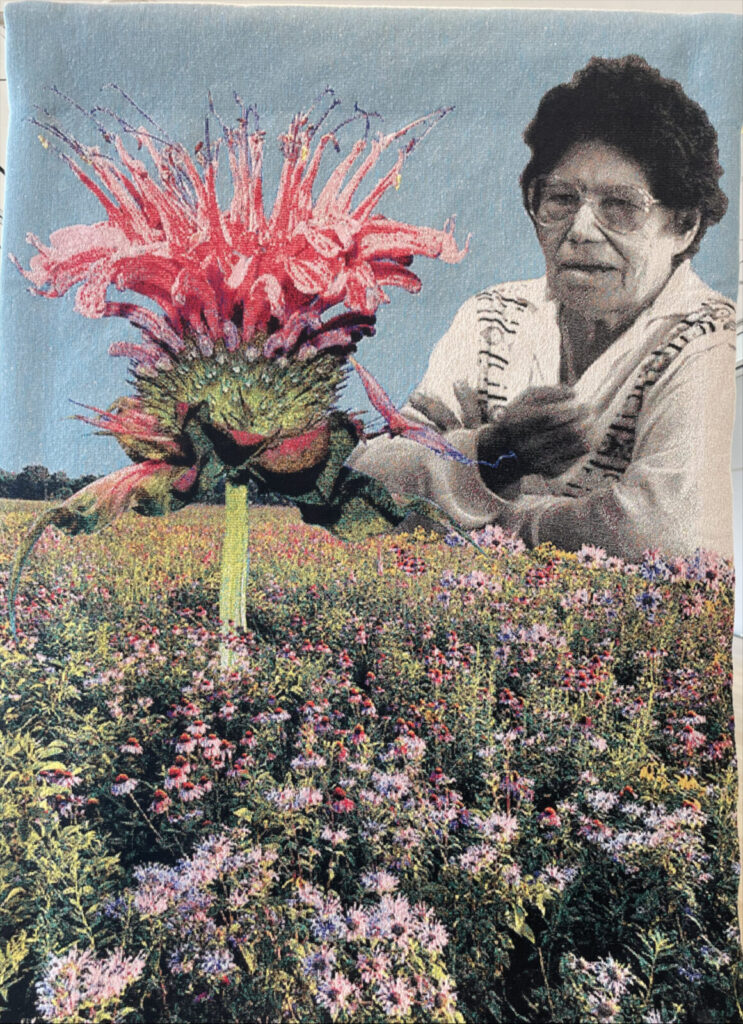

Faustina “Tinti” Deyá Díaz (1940–2021), an environmental activist in Puerto Rico, stands among blooming coffee flowers in Carolina Cayedo's 'We save our seeds for the following season' at the Clark Art Institute.

While Sandoval is working in abstract patterns in black and white, Caycedo works in vibrant color. She weaves portraits of women and plants, talking with them and their families in friendship and respect.

In the pavilion at the entrance to the Clark, the elder Mohican herbalist Ella Besaw appears, foraging in a wildflower meadow. Caycedo shows her gathering wild bergamot, a medicinal plant her people call Number 6 for the many ways they find healing from the plant and flower.

Caycedo reached out to Besaw’s family, asking to honor her as an elder of the Stockbridge-Munsee community of the Mohican Nation. Though the community now lives in Wisconsin, their homelands are here, and they keep close ties in these hills.

Besaw appears here in a summer meadow, and at her feet Caycedo has set tobacco leaves and Besaw’s words, “When you take from Mother Earth you can give back by sprinkling tobacco” — when she gathered wild plants, Besaw would give a gift to the plants and the meadow and the ecosystem in return, in thanks.

She looks out firmly from the first in a series of tapestries in Jacquard weaving, in cotton thread, We save our seeds for the following season. A story lives in each one, Caycedo said, and she has made them through many conversations with the women in the tapestries, if they are alive, or with their families.

Caycedo lives and works in Los Angeles, and she travels and connects with people from northern Alaska to the Caribbean. In each of these works, she honors a woman who has led her community, loved and protected her people and their land.

Faustina “Tinti” Deyá Díaz (1940–2021), an environmental activist in Puerto Rico, stands among blooming coffee flowers. In a bid to stop a multinational open-pit mining project, Caycedo explained, Díaz founded Casa Pueblo a ‘community self-management organization’ that has grown local solar energy, a butterfly reserve and the community’s economic independence, including Café Madra Isla, a sustainable coffee enterprise.

And beside her, Meda picks crowberries with her daughter to take to the island of St. Paul, where the berries had collapsed in the increasing heat from climate change.

An alligator takes its tail in its mouth in an echo of the mythical ouroboros in Allison Janae Hamilton's sculpture at the Clark Art Institute.

Wiesenberger honored the depth of Caycedo’s connections with people over time and the depth of her research. She met Meda researching sphagnum moss, he said. She has Japanese American women growing gardens in internment camps in World War II

relationships with plants.

And she has drawn on her own experiences. Across one wall, nettle leaves and flowers overlie a circle quartered in red and black, yellow and white. With Williams College students, Caycedo painted a mural of a Stockbridge Munsee medicine wheel, colors representing cardinal directions, seasons, life stages or ceremonial plants. She turned to nettle for healing after she gave birth to her second child, she explained, because nettle helps the woman’s body to recover and encourages her milk.

People have natural worlds inside our bodies as well as outside, she said. And they interconnect in more ways than we know. Outside near the reflecting pool, a large and vivid mural honors yarrow. Caycedo imagined this painting when Ruth Bader Ginsberg died, she said — asking herself who will really be there for us in moments of need?

Mi cuerpo / Mi territorio, My body / my land, makes a strong statement of independence, and Motherhood will be wanted or will not *be* — will not exist, lifts up the Marea Verde, the green wave, movement that spans Latin America, defending abortion rights there, even in Catholic countries, even while they are threatened here.

She spells out those words along the windows overlooking the reflecting pool, in letters born on poles like Chocó staffs from Colombia. They are tools, conduits, she said, and everyone can carry one — you make your own. Someone who feels they carry masculine energy will choose wood from a feminine tree, and someone who feels feminine will choose a masculine wood, for balance. She created these not only for this show, but for the future, she said … like saving seeds.

A wooden gate strung with bright tiles and glass opens into Pallavi Sen's garden at the Clark Art Institute.

Pallavi Sen has done that literally. In her garden up the hill, more than 90 kinds of plants are growing on the terrace. Many she grew up knowing, she said — they are not necessarily native to South Asia, to Bombay where she was born, but they could withstand the heat, and people grew them.

Now she lives and works in Williamstown and New York, and she teaches at Williams College — and she has created this living place with students this summer. They are caring for the garden together, planting and watering, learning to look closely, drawing the plants as they grow and bloom and fruit, saving seeds.

She has drawn the practice of gardening into her art, she said, as she thinks about ways of being in a garden, how to teach and study and make art in a living and changing place.

She began gardening four years ago in the pandemic, as she was looking for ways of being as an artist that would not conflict with what she believes — as a sculptor working with found objects and plastics, she knew she was making work that would end up in landfills.

Now she studies seeds and weaves trellises for plants who naturally wind upward. She makes artwork in the garden, ceramic tile, a bird bath. And she gathers plants for birds, companion plants that grow well together, plants that will flower across time, in July and August and September.