Spruces are standing tall overhead, dark and sunlit in the long blue dusk of a Norwegian summer. On the earth in the ring of trees, a ring of light is glowing. A portal has opened between Williamstown and the boreal forests outside of Oslo.

Natural places can hold a living energy in Edvard Munch: Trembling Earth at the Clark Art Institute. He invokes them magnetically in ways that may surprise people who know Munch only for the Scream and a few other familiar images. The painter known for existential crisis, for a figure holding himself together in anguish, painted more than half of his works as intimate studies of the land.

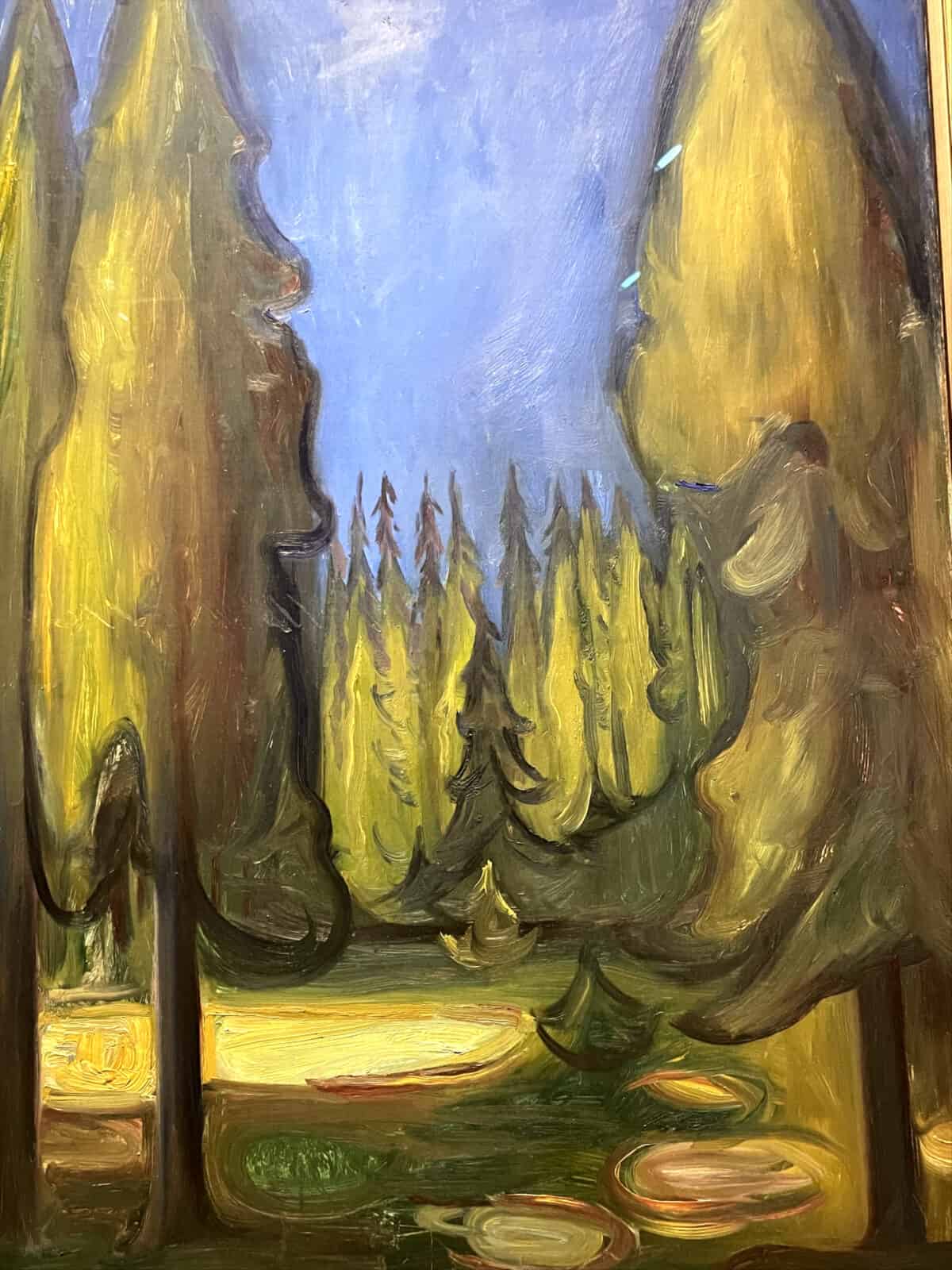

Edvard Munch's Dark Spruce Forest (1899) shows trees tall and glimmering in the dusk. Press photo courtesy of the Clark Art Institute, Munchmuseet and Artists Rights Society, New York

In Dark Spruce Forest, he “reveals and revels in the tree as a power source, alive with light and electricity,” Ali Smith writes in the opening of the show’s catalog — “like it’s harnessed the eye or the ovum that the sun behind it is, and it’s a picture of how that tree conducts the world, conducts the sky like the sky’s its orchestra.”

As an internationally awardwinning Scots novelist, and journalist who regularly writes for the Guardian, she imagines a half-fictional encounter as she explores Munch relationships with land and water and trees. She sees a mystery and vastness expressing feelings too large to contain.

‘Munch reveals and revels in the tree as a power source, alive with light and electricity.’ — novelist Ali Smith

“(These paintings) show a side of Munch you may not know,” said Jay A. Clarke, Rothman Family Curator at the Art Institute of Chicago.

She returns to the Clark this summer, where she spent many years as curator of works on paper, to create this show with Trine Otte Bak Nielsen, curator of Munchmuseet, the Munch Museum in Oslo, and independent curator Jill Lloyd.

The show explores Munch’s work from intimate perspectives: his family, relationships, passions and philosophies, and the times he lived through.

His canvases move with passion and vivid color, said Clark associate curator Alexis Goodin. She feels the joy of the painting in the layering of paint, she said, and surprise acts of chance, drips, glazes melded together.

She and Clarke acknowledged a jagged edge in Munch’s lived experiences. He lost most of his family to illness when he was a boy, Clarke said, and he grew into an isolated, irascible, intense man. He had affairs, short and long, and conflicted to the point that one confrontation ended in a hand injured by a gunshot. In the middle of his life, he checked himself into a clinic to deal with alcoholism.

He also lived in intense times, between 1863 and 1944 — not only Norway’s independence from Sweden and two World Wars, but the release of new understandings of the world — Darwin and Einstein, the immense variety tenacity of life, quantum particles, geological time.

Clarke has grouped the work into themes, ocean, storm and snow, sun … She opens the show in the deep woods. In the northern forest, Munch evokes trees in abstract masses of color, washes and glazes, oil paints sometimes thinned almost to watercolors. His taiga shows vast stretches of green blowing in the wind.

In the foreground, one fir has worn by weather into an irregular shape. In the deep blue light, the tree looks like the silhouette of a face in profile. A long face with strong bone looks three-quarters away from the frame, out over the open wood.

The living plants are shapeshifting, seeing and sensing — Munch writes in his diaries and letters:

‘The Trees stretched

their Branches

towards the Sky –

and out of the Air’s

Nitrogen

… the Trees separated

from the Earth and

began to move –

and they became Humans …’

Clarke points out openings in the limbs. They remind her of eyes and mouths, she said, and she finds something powerful and even ominous in them. But Smith, who sees the same expressions, hears the trees talking.

Munch paints them, Smith says, “as the tellers of the tales, like they’re the real narrative authorities, the most powerful real thing and symbol in the picture both at once.”

In Norse folktales and legends, forests are often places of power, Clarke said, like the ocean and the shore — home to the spirits of trees and the magical beings who live there. Munch writes …

‘The Boulders came to life

– and stirred – became mermaids

and trolls – the Forest’s dark

darkness gave birth to creatures –

Serpents moved under

the leaves –’

Edvard Munch, Summer Night by the Beach (detail), 1902–03. Artists Rights Society New York, press photo courtesy of the Clark Art Institute

His own feeling and experience transform the land and sea around him. The woods and the water reflect his state of mind. In a time of animated passion, stirred by a woman, his vision changes.

Many of the works in this show center images of pain and desire, Clarke said, the beginning of an affair and the end. In his lithographs, a man and a woman stand at the water’s edge, and the changing light reflects their changing states.

‘And Nature was made more beautiful by

You – Through my eye’s

retina that was awakened by

your beauty –

I saw that the sea had

become larger – the waves had become

softer – the Forest a darker

green –’

Edvard Munch, Fertility, 1899–1900. Canica Art Collection, Oslo. Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York. Press photo courtesy of Clark Art Institute

In some a man and woman stand entwined, but more often in their body language they are distant and pulling away. Munch describes the colors here as distinctly as his own nerves firing — but not the woman. In the paintings and prints here too, the women often have no clear expressions. At most they have what Clarke calls a kind of hazy stare, and more often a blur for a face.

He works in masses of color, thick brush strokes and abstract forms, and he speaks and writes of vision with precise clarity. Many of these scenes catch the shades of dusk and night, and his paintings in daylight refract like prisms. In his writing, he explores crystal structures and the working of the eye — retinas and pupils — and vivid hues.

‘… When I go out on a light summer evening

and become mild in spirit

when the eyes after

the sun has set dilate in order to perceive

all these gentle golden light colours …’

Clarke traces the the qualities of light, as his work moves through the show in time and space — moonlight on the water, the shore in a storm, a starry night with light on the horizon from a distant city. And woven through them, she traces a darkness, an absorption, an intensity, a sense of isolation.

She pairs some of his brightest light with some of his clearest images of death and dying. Munch wrestles with the limits of life and consciousness. Looking for ways to extend awareness a human lifespan, he writes that crystals bring life into stone.

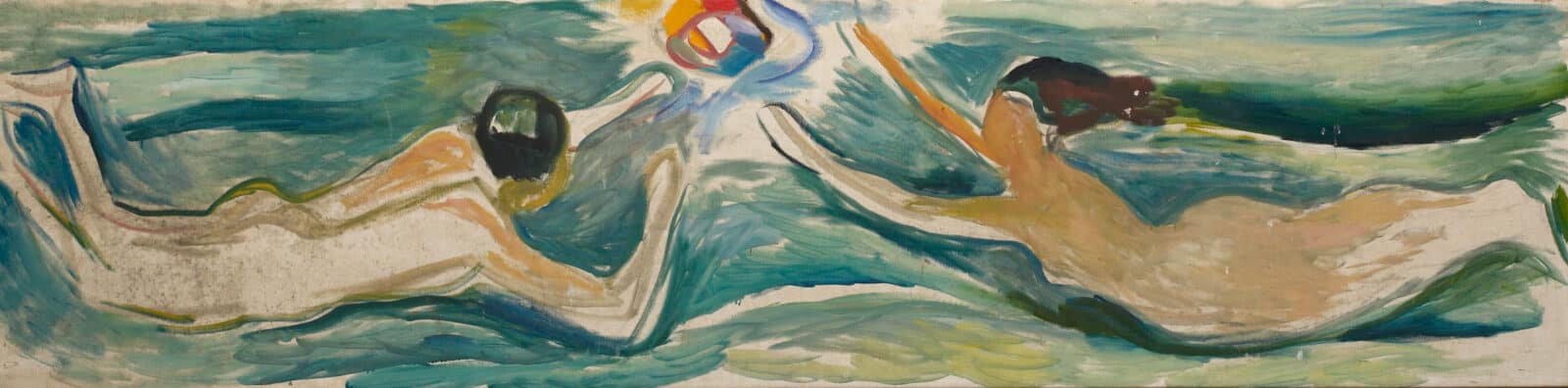

His trees share the earth with bones, on the walls around his paintings of the sun. On the shoreline, rounded stones pulse with color. In the water, two people swim, reaching for a rainbow globe of light, and their legs merge in shadow, like whales. The sun beats in concentric circles across the sky like an afterimage.

Meeting in Space, Munchmuseet, Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York. Press photo courtesy of Munchmuseet