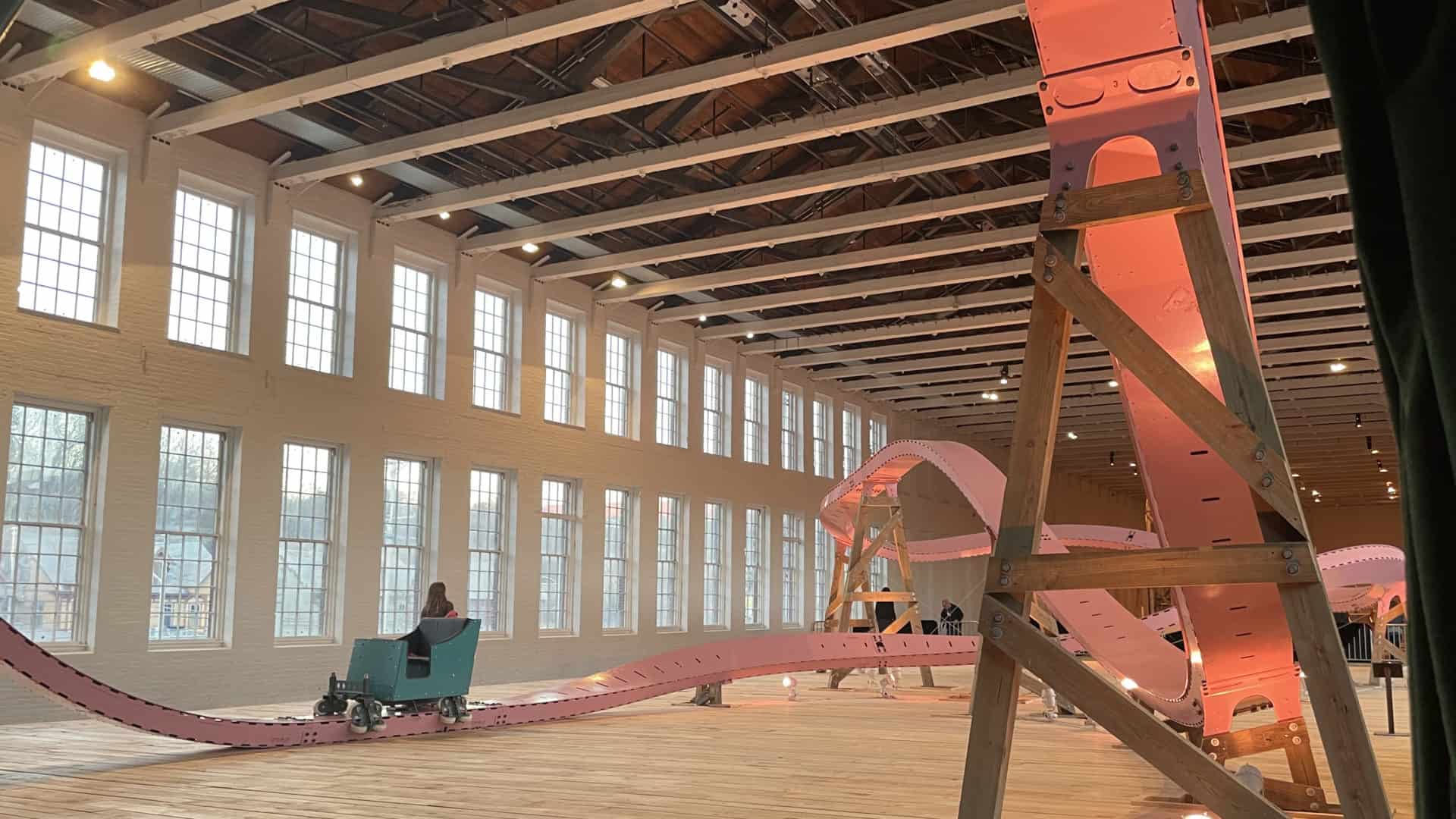

The solo rider in the single cart drops a full story in a rush, lifting both arms overhead and shouting, and the cart slues into a wide arc. Internationally acclaimed Los Angeles artist EJ Hill has created an installation out of experience on an edge of terror and delight.

He has imagined a real, rideable roller coaster in a vast room in an old mill. This fall, Hill has opened Brake Run Helix, the newest exhibit at Mass MoCA.

“Extremes of physical sensation move you to feel something in your gut,” says curator Alexandra Foradas, watching the rider skim backward around the loop overhead.

To work here in this space, the coaster runs entirely run on gravity. The attendant waiting to winch the car back up to the top says that when he sees the roller coaster on a clear day, sunlight will cross the sculpture in bright bars, breaking through it. Then he saw it on a cloudy afternoon, with the lights on within the wooden frame, and the whole structure glowed — “It just exploded.”

EJ Hill's Brake Run Helix brings a rideable roller coaster to Mass MoCA.

At night, as the light dims, it all feels like a single piece, Foradas said, and when you’re riding, you can look through the long windows and see the mountains outside touched with sunset light — and she finds it magical.

She first encountered Hill and his work when he exhibited at the Venice Bienale in 2015, she said, and she reached out to him in 2018 after seeing his installation at the Hammer Museum in Los Angeles. His worked there looked beautiful and intensely demanding, emotionally and physically.

He created a winner’s podium at the Hammer, she said — and he stood on it every hour the museum was open. For weeks. He made himself part of the work, so that everyone who walked into the room would see him.

“It was very draining,” she said.

He embodied and faced “ever-present threats of exhaustion and debilitation,” says Makayla Bailey, the exhibition’s co-editor and interpretation consultant. As a writer and curator in New York, she has served as a joint curatorial fellow at MoMA and the Studio Museum in Harlem, and she is now co-director of the Rhizome digital project with the New Museum.

“This installation was a ritual reclamation,” she wrote, considering his Hammer exhibit. “Hill ran victory laps around his former schools, collapsing into stillness in the form of daily, enduring presence on a podium (christened Altar) in the gallery.”

Here, as in an installation at the studio Museum in Harlem, “his unceasing, perpetual presence during museum hours traced a grueling endurance from one day to the next.”

After these shows, and the pandemic, he was interested in looking for spaces in his practice for care and respite, Foradas said. She sees an impulse toward withdrawal in some of his most recent work, she said, including the Whitney biennial, where he contributed a single blank page of pink paper.

Here he turns to a practice that places fewer demands placed on his own body. In the place of enforced stillness and strain, he has created an act of spectacle and excitement in a performance space that has already come alive with people and music — Brake Run Helix opened with dance party.

And he is turning the lens around, Foradas says, inviting speculation about who is watching whom. This roller coaster shifts perspective. Instead of full train cars in an oblivious crowd, one person can climb into this cart at a time, riding alone with a crowd watching.

“To turn a roller coaster into a performance encourages you to question the degree to which all public acts are a performance,” she said, “and especially for EJ Hill as a queer Black man — in North Adams and Berkshire County especially.”

In the time he has spent on site here, helping to get the show ready to open, he has been aware of the way people look at him. Just walking up Main Street or into a coffee shop can become performances, whether he wants them to or not — when all he wants is a hot cup of coffee and a few minutes of quiet.

“He is looking for a more capacious exploration of the embodied experience of art,” Foradas said. “For him, roller coasters are already art. … Roller coasters are an experience of terror you opt into, with your consent. His work is a reclaiming of experience, of (adrenaline) and danger.”

‘(EJ Hill) is looking for a more capacious exploration of the embodied experience of art.’ — Curator Alexandra Foradas

He has turned to rides and amusement parks out of a lifelong fascination, she said — he has loved riding roller coasters since he was a boy, and he has an equal fascination with their history. The exhibit pays homage in photographs he has taken over the years of historic rides at historic parks. In one of his earlier installations, Prospect 5, he centers a ferris wheel from a New Orleans park that closed after Hurricane Katrina.

But roller coasters have a more complex and challenging history than speed and thrill and the limits of physics.

“Roller coasters as sites of access — and prohibited access — to places of leisure and joy,” Foradas said.

Unlike the kinds of fair and carnival rides sometimes owned by traveling families for generations, roller coasters began as amusement for nobility — he traces them back to ice slides in Russia in the 19th century.

Innovative designs for roller coaster tracks and carts form a kind of music in motion in EJ Hill's Brake Run Helix in Building 5 at Mass MoCA. Press image courtesy of Mass MoCA

In America, until the 1960s, amusement parks operated on a Coney Island kind of model, she said. They went up near cities, easy to get to and priced inexpensively by the ride, so everyone could go.

When federal laws mandated desegregation, Black families were denied access to places of leisure, Foradas said. In the years when Black Americans were often barred from public parks and pools, amusement parks increasingly went into private hands. They moved away from urban centers and public transportation, reachable only by car.

And they moved away from light fees for each ride, toward a flat fee at the gate — which is much more expensive and more likely to be prohibitive to families on slimmer budgets.

“They’re like museums,” Foradas said, “but the entrance fees are even higher.”

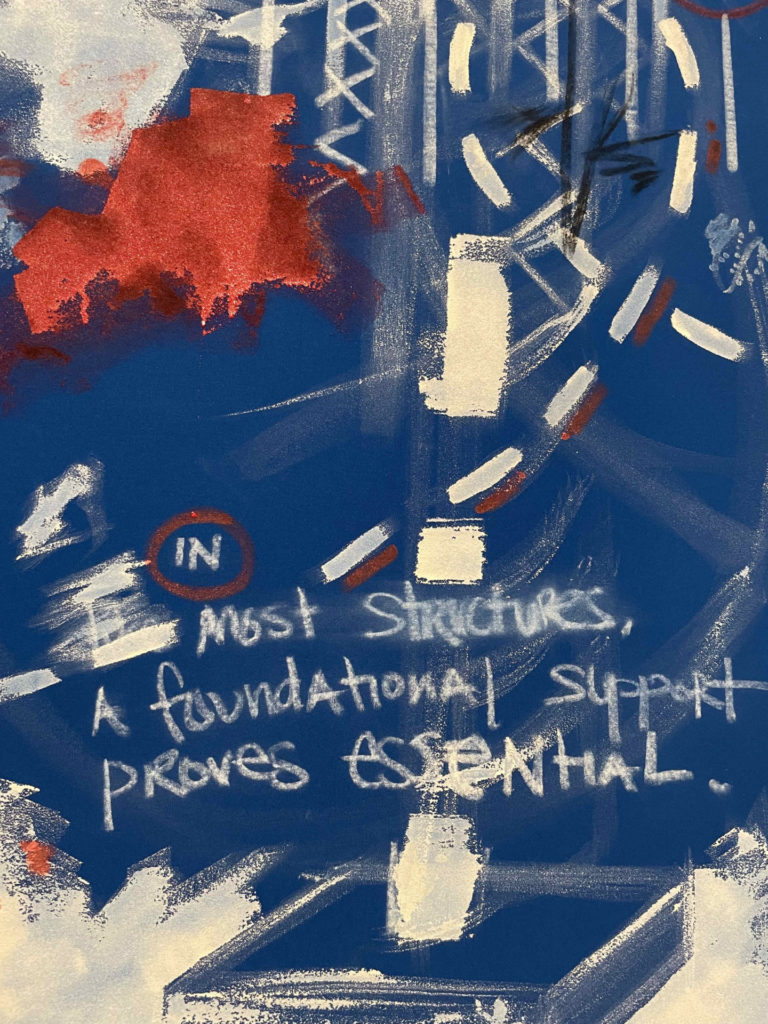

And so she sees Hill in Brake Run Helix acknowledging a history of exclusion and envisioning a future of strength and confidence and pleasure. He calls some of his paintings here joy studies.

“Joy isn’t something with an end,” she said. “It’s something you continue to learn.”

‘Joy isn’t something with an end. It’s something you continue to learn.’

In his photographs and his repeated images of clouds, she sees a motion upward, ascent into a better place — visions of Black futurisms, moving toward a spaceship or toward the heavens. As he wrote in Neon in the Hammer show — “We deserve to see ourselves elevated.”

(In that way they recall Nick Cave’s installation in this space in 2016, where visitors moved through a gleaming maze of illusions to climb a the ladder into a vibrant world dense with trees and birds and color, and found objects made as caricatures that he re-envisioned as whole and powerful beings.)

Hill’s work touches on themes deep and close to him, Foradas said. He has talked with her about his work as a very vulnerable process. Even though he does not appear here in this work, it is a kind of exposure, to reveal work he has been growing and evolving, sometimes for years, to people who hasn’t taken the time to get to know him.

A green curtain catches sunlight behind the pink roller coaster track in EJ Hill's Brake Run Helix in Building 5 at Mass MoCA. Press image courtesy of Mass MoCA

He also celebrates what he loves, even in the face of ridicule. He has chosen pink as a thematic color, she said, because he has always loved it, and as a child he was made fun of for loving it. He has swept color through the room here in grand style — the roller coaster runs on pink tracks.

In the center room, he shows paintings of roses in bloom, along with neon clouds and the wooden scaffolding of rides against the sky. They stem from an interest in nurturing and growth, Foradas says, and a deliberate respect for softness and femininity.

He has named the roller coaster Brava — the word people call out in excitement at high points in a performance when they are riding excitement, or when they throw flowers. In Italian, brava means brave, showing courage and endurance. And it means that for a woman.

“Brava is what we shout to a female or femme-identifying performer,” Foradas said. The word exists to celebrate a woman, and she is often the star.

In the pandemic, Hill has been painting and drawing flowers, and he told her that in these works his grandmother finally saw what he was doing as art. And she’s someone who has always gardened, has always had her hands in the dirt.

Along with the pink swirls of paint and loops of track, he brings in deep, dark green velvet, as an echo of plants, Foradas says, and also as a note of performance that sounds all through the installation. While the rides themselves are a show, the wooden platform for the coaster can also become a stage for popup music and theater.

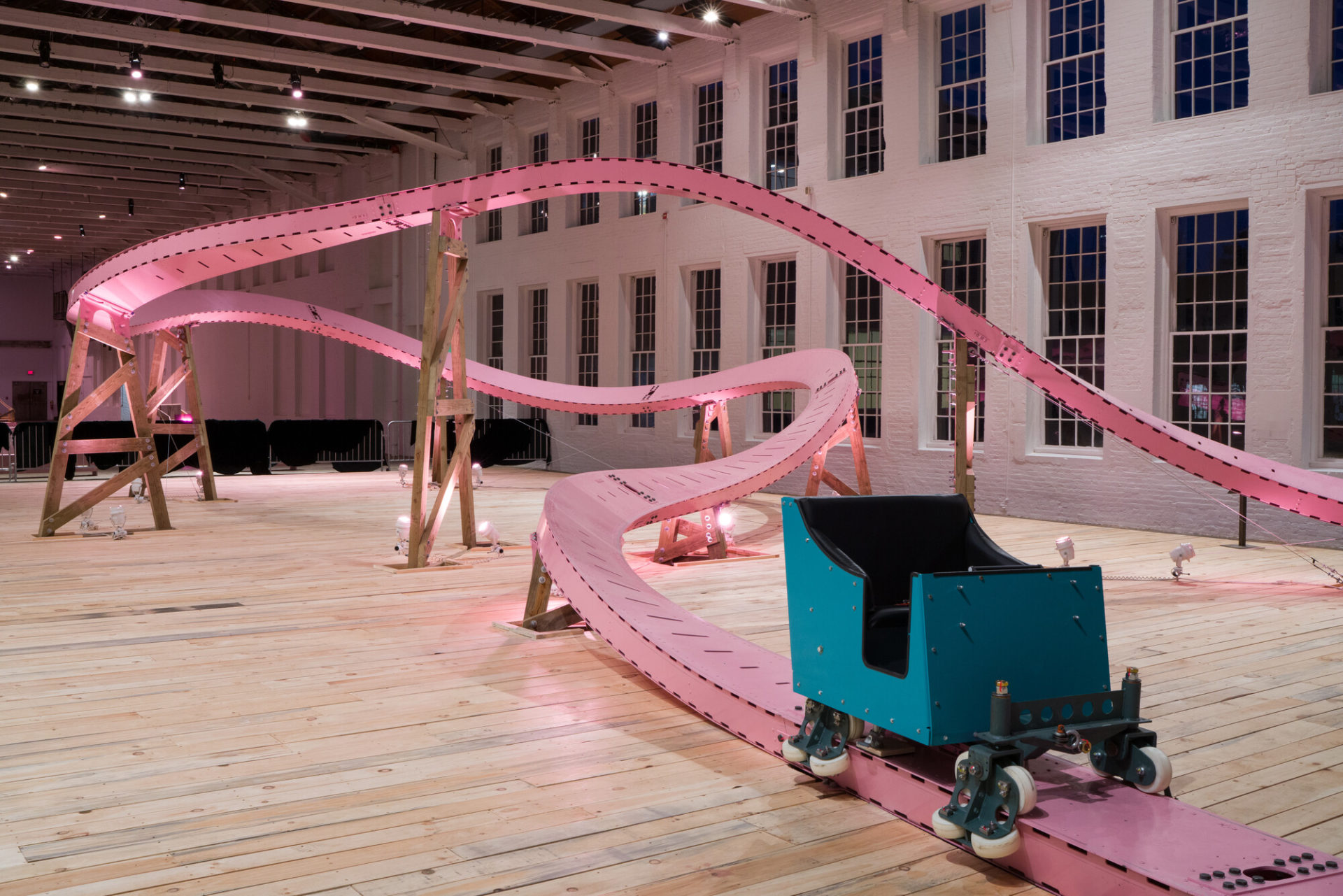

And at the center, it is a work of engineering as well, trading elements of supersleek monoliths and backyard bike jumps. How did Hill design and build a roller coaster inside a museum? He and Mass MoCA’s fabrication crew have worked with Skyline Attractions to create a brand new design, Foradas said.

A green cart rests at the foot of the pink roller coaster track in EJ Hill's Brake Run Helix in Building 5 at Mass MoCA. Press image courtesy of Mass MoCA

Hill wanted to fit his coaster into the existing architecture, she said. The loops form a figure-eight as high as the mezzanine, and physics dictate the run from there. Since it’s gravity-powered, the coaster has physical limits on its height and drop and a finite length of track.

Skyline made the track and the cart and the struts from bent and riveted steel, she said, and the underlying structure is made of raw wood — Hill wanted a DIY feel, something you can make in your backyard. He has re-used almost all of the materials from past exhibits, planed down and reshaped.

The grey boards come from Glenn Kaino’s boardwalk, in the show that has run in this space through September, with his shadow play of protests around the world, and Deon Jones singing his unflinching R&B cover of U2’s Sunday Bloody Sunday.

Around vast coil of Brava, Hill has envisioned three more trains on coaster tracks, tapping into the history of roller coaster design — they are all speculative carts, Foradas said, and they all work. Hill calls them collectively metaphysics for a pink sonata, and the cart in front can move through the space, becoming a kind of dance notation and allowing him freedom to adapt.

‘Both are forces on your body, physical demands on you that social structures are placing. … It has poetry to it too — full stop, full speed, spinning.’

On the weathered boards and in the galleries, sculpture and paintings glint with found neon, all of it from Lite Brite in Kingston, N.Y. They created the neon script that reads ‘Promise Me Peril’ and loaned neon from other projects — on the freestanding carts, the the heart on Heartline already existed, and the bar on Stratus.

She imagines the shine in the gallery at night, on a winter afternoon when it’s dark by 4:30 and the pink lights on the roller coaster light the room. The lighting holds its own drama then, a momentum like the name of the show. A helix is the moment in the ride where the G forces are strongest, she said, as they can be in a corkscrew. And a brake run is a space at the end, to let the cart slow down.

“Both are forces on your body,” she said, “physical demands on you that social structures are placing. They’re only metaphors here — we don’t have either of these structures. He has titled the work for something not present. It has poetry to it too — full stop, full speed, spinning.”