The cloth is the deep red of zinnias and bee balm, with golden leaves and birds, and seeds strung like beads. At the doorway into Daniel Chester French’s historic art studio, an egungun robe is standing in welcome this summer, inviting people into a creative space.

Walk in and turn to look at the shelf above your head, and among the plaster casts of hands that French made here a century ago you will see one ebony hand.

Georges Adéagbo, an internationally acclaimed artist from Benin, has come to Chesterwood to open a new site-specific art installation, Create to Free Yourselves: Abraham Lincoln and the History of Freeing Slaves in America. He is holding a conversation in French’s barn and studio and in the Morris studio for artists in residence — recasting French’s spaces with his own paintings and sculptures, ideas and found objects.

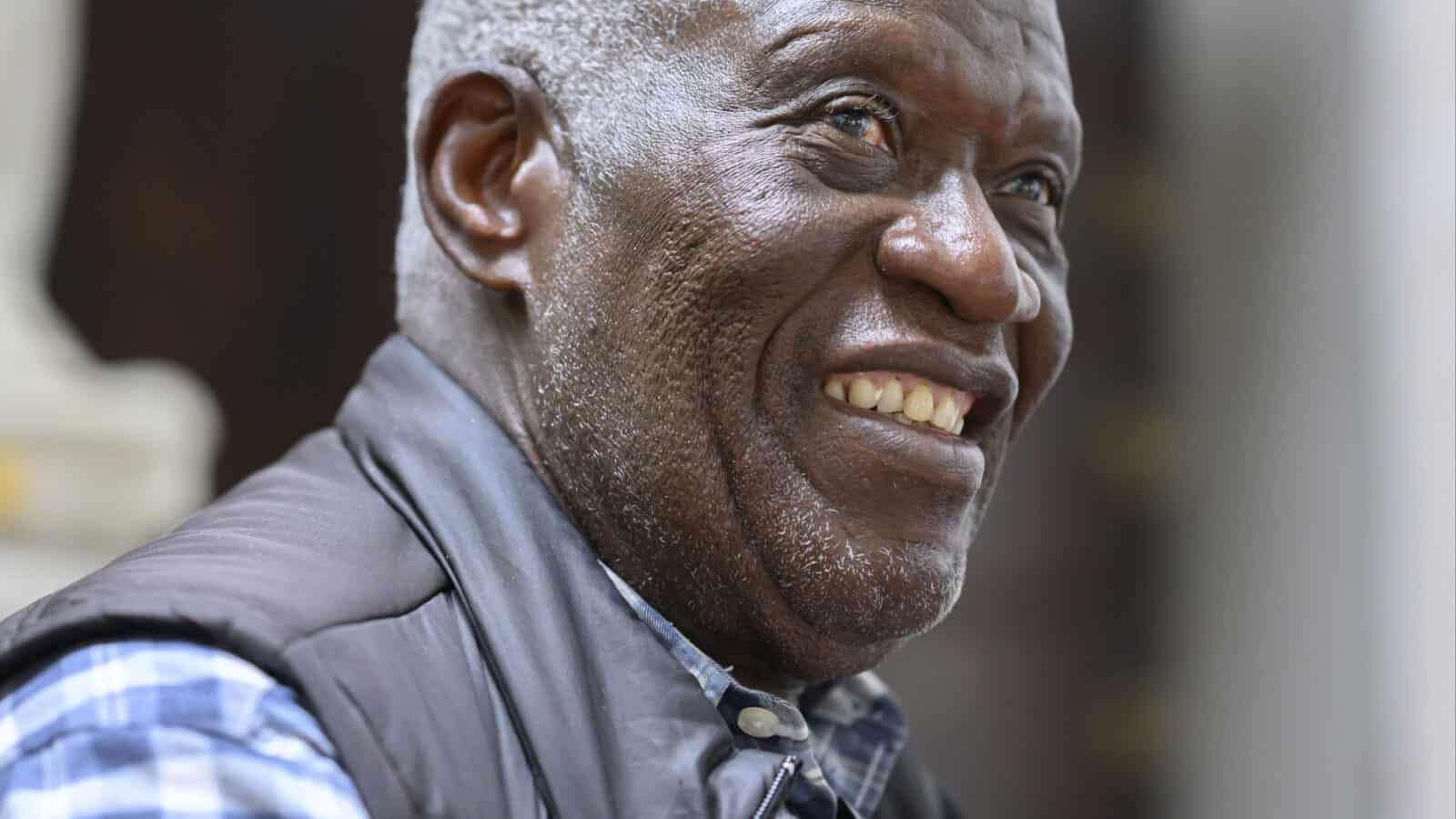

Internationally acclaimed artist Georges Adéagbo looks around the Morris Studio as he creates a site-specific art installation. Press photo courtesy of Chesterwood.

Conversations across time

Internationally acclaimed artist Georges Adéagbo has come from Benin to open Create to Free Yourselves, a site-specific art installation at Chesterwood — a conversation and exploration of President Lincoln and the Emancipation Proclamation, enslavement, courage and freedom.

He began this work last winter in an arts fellowship with the Smithsonian and Lincoln’s Cottage in Washington D.C. He has evolved the work here this summer, and in September he will bring a new incarnation to the Smithsonian’s National Museum of African Art, to show and then enter into the museum’s permanent collection.

Among the Yoruba in West Africa, he says, an egungun is a robe worn to dance and invoke the ancestors. People will move around the village and spin, channeling questions to people they love who have gone on before them.

Brilliant color gives a new contrast to a barn filled with northern sunlight and sculpture in white marble. French has also created connections to people a community has lost, Adéagbo says — and one honors the soul of a president who had just been assassinated in French’s lifetime. He created the form of Abraham Lincoln for the Lincoln Memorial in Washington D.C.

The work moves Adéagbo. President Lincoln has moved him to cross the Atlantic, he said, to travel and research American history, past, present and future. Adéagbo has created and shown his work around the world, from Munich and Berlin and Madrid to the Venice Biennale and the Art Institute of Chicago. This past winter, he came to Washington D.C. for a Smithsonian fellowship and artist residency at Lincoln’s Cottage.

Georges Adéagbo holds a mask as he creates a site-specific art installation. Press photo courtesy of Chesterwood.

He creates each new work in response to the place where it will live, he says. He gathers a collage of ideas, working with a team of artists in Benin. Here in a painting they have recreated Lincoln’s handwriting from a letter Adéagbo read last winter:

If slavery is not wrong, then nothing is wrong. I cannot remember a time when I did not so think and feel.

“When God made made people, he did not make us enslaved,” Adéagbo said, speaking in French, his own language in Benin. “How were we made enslaved after the creator made us to be free? Emancipation is the proclamation that we *are* free.”

He hears President Lincoln reasserting that all people are and have always been free — from the beginning and in the future, in the minds of those who understand love, in an expanding universe, in a whole and creative world.

‘When God made made people, he did not make us enslaved … Emancipation is the proclamation that we are free.’ — Georges Adéagbo

He first came to Chesterwood on a winter night. He and his friend and curator and translator, Stephan Köhler, Chairman Kulturforum Sud-Nord, remember the light at dusk, sunset on the bare trees. They had a first impression of snow, they said, and a sense of the closeness of nature and art.

Margaret Cherin, senior site manager at Chesterwood, heard of Adéagbo’s work through the National Trust, and she invited him to the Berkshires. In the spring they kept in touch, she said, while he worked on the show in Benin. He would ask her for photos from the Chesterwood collection. They talked about French creating work to hold Lincoln’s memory.

“French’s work was his life,” Adéagbo said, sitting on the porch and looking over the hayfield. “He did something, he made something, no one else could.”

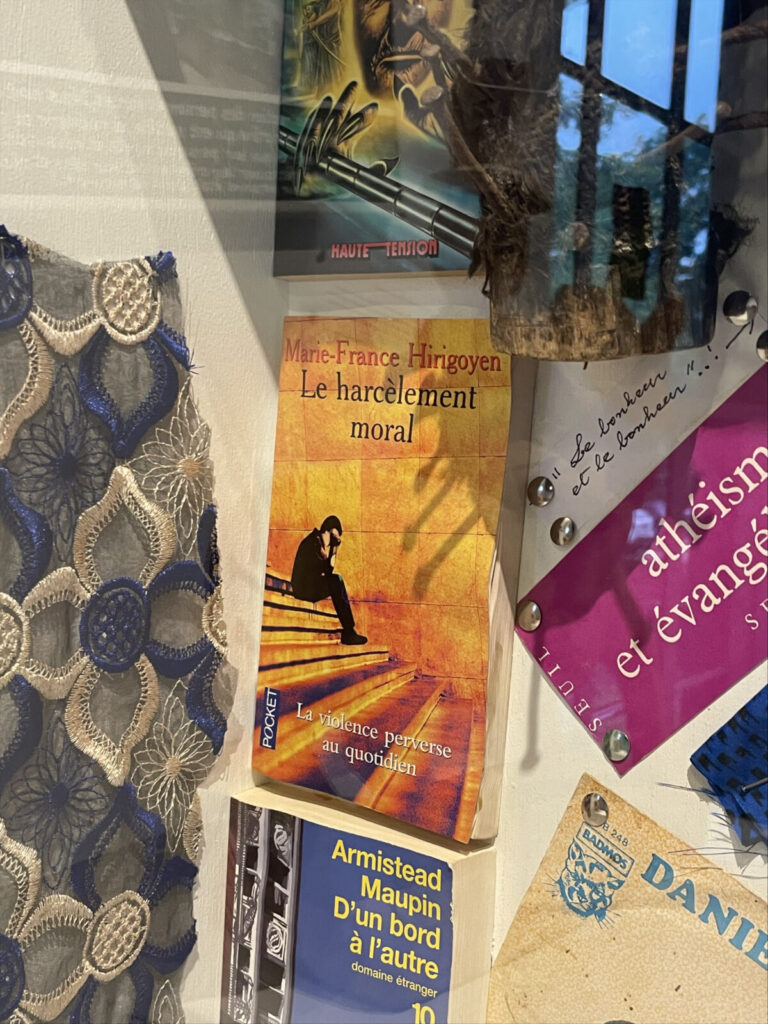

A wood sculpture from Benin looks across the Morris Studio at Chesterwood, filled now with books and music and artwork in Georges Adéagbo's art installation at Chesterwood.

“… It’s the art that makes the artist — not artist who makes the art. The artist is the messenger who finishes the the creative work that nature begins.”

As Adéagbo explored his own project, he read President Lincoln’s writings at the Library of Congress, including documents they do not usually show in the original, to preserve them — the emancipation proclamation, letters, journals and speeches,

This summer, when Adéagbo returned to Chesterwood, he and Köhler and Cherin went exploring together. They talked about local history and the writings of W.E.B. DuBois.

She brought them to Shaker Mill Books in West Stockbridge and to Seven Arts Music Shop in Stockbridge in the mews, to look for vintage records. They searched through flea markets and tag sales.

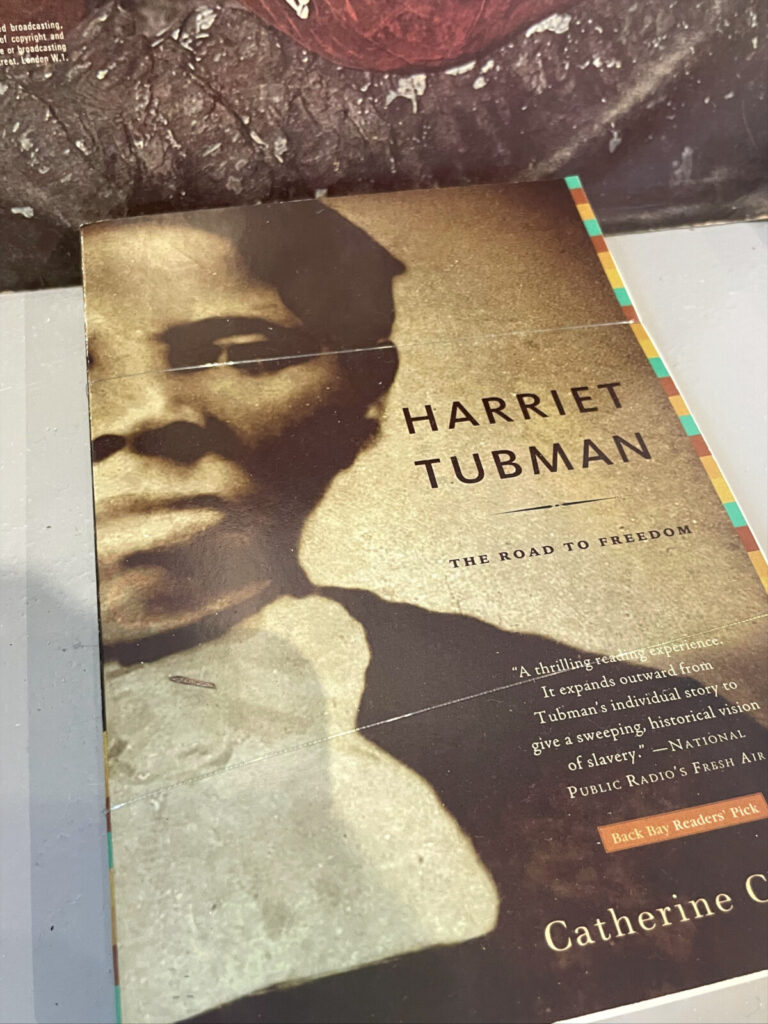

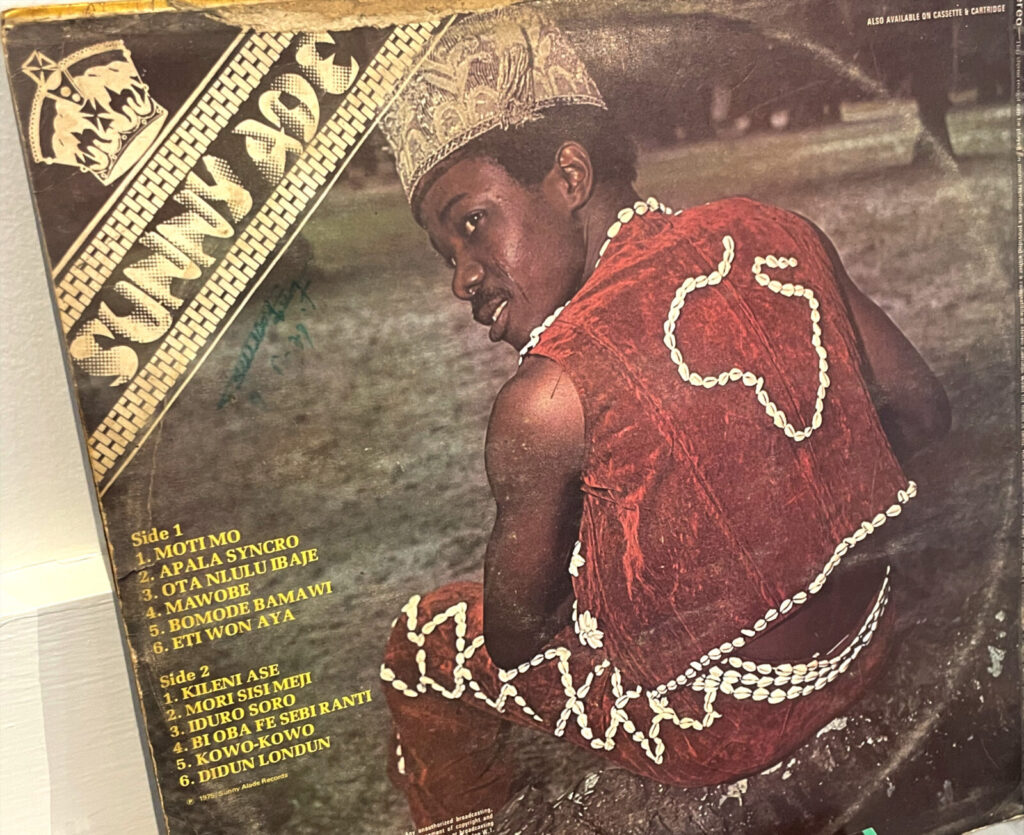

From those quests, Adéagbo brought back albums of the music of Sunny Ade and the National Jazz Orchestra of Dahomey. Lives of Frederick Douglas fan out beside a record of Kalil Gilbran’s The Prophet, read aloud to music composed by Arif Mardun.

And Walter Benjamin’s essays consider the power of stories. Benjamin often writes about how people gather and keep knowledge, Köhler said — and how people create. Benjamin argues that libraries need to be open, not constrained by categories. They need to be wide-ranging, eclectic, to encourage new connections and relationships between ideas. And they need to hold more than books. Voices and objects and primary sources can hold memories.

“Benjamin often says you have different remnants,” he said, “and they are shadow microactivists. We have a Lincoln monument, but we should not forget all the others fighting for freedom who have no monuments.”

Internationally acclaimed artist Georges Adéagbo and curator Stephan Köhler look through books and music, sculpture and found objects as Adéagbo reimagines his site-specific work in the Morris artist studio at Chesterwood. Press photos by Gregory Cherin

Adéagbo brings together a polyphony minds at work, novelists in many languages, pop culture, thinkers probing psychology and political science and global trade. They explore 21st century challenges and influences going back more than 400 years. And they remember lived experiences.

A woodwork sculpture from Benin shows President Lincoln riding on horseback. Lincoln’s Cottage is a home for veterans now, Köhler said, and in his lifetime Lincoln would stay there in the summer. The White House was too hot and too crowded, and he was mourning for his third son, William, who died in 1861, when he was only 11 years old.

In that long, hard summer, Lincoln would ride to work every morning, and he would always ride alone. Adéagbo feels empathy for his grief and courage. Around the room, he has set wooden masks a woman would wear. They come from a matrilineal tradition, he and Köhler said, like the egungun, calling to lost loved ones, forging relationships across time.

‘You are relying not only on what your eyes see but what you feel with your heart,” Köhler said, translating, “using not only the visible but the invisible to communicate with the invisible.’ — Curator Stephan Köhler

“You are relying not only on what your eyes see but what you feel with your heart,” Köhler said, translating, “using not only the visible but the invisible to communicate with the invisible.”

That sense of feeling and connection beyond words — flows through and animates and unites the mosaic of Adéagbo’s work. It is why he roots so much of his work in connections to place, he said. A place can hold a spirit, an ecosystem of experiences. As he studied abolitionism in America, he went to West Virginia to see Harper’s Ferry, where white abolitionist John Brown led a revolt in the cause of emancipation, and he brings those memories here in conversation with French’s Gilded Age home.

Adéagbo sits on the porch outside French’s studio, two stories tall and turned toward northern night. French took down the original farmhouse to build the large dwelling next door in Italian stucco. Afternoon sun touches his lawns and gardens.

In his studio, at the front and center of the room, Andromeda is lying on her rock in the sea. She was French’s last work, Cherin says. On her left hand, Adéagbo has set a memorial sculpture from Benin showing scenes from someone’s life and home, grain in the fields. On her right, a new Andromeda made from Ebony is lying beside her.

In both sculptures, her wrists are chained to the stone. She is waiting for a sea serpent — she is a sacrifice, and in this moment she has been left to die for her country as President Lincoln died for his, Adéagbo said. In the original Greek myth, Andromeda comes from Ethiopia. And she has come here in a new form, a woman from Benin flying halfway around the world.

Georges Adéagbo hangs a mask as he creates a site-specific art installation. Press photo courtesy of Chesterwood.