Nora Krug took photographs on a high school class trip in 1994. In black and white film, her classmates sit on the grass, looking at their hands, and one is leaning elbows on knees, their hands cupping their face from chin to temple.

They have come to Birkenau, the largest camp in Auschwitz. The past is tangible around them — more than a hundred buildings and the ruins of the gas chamber and crematoria.

“I remember walking past the train tracks, the barracks and the electric fences,” she writes decades later in her graphic memoir, “past the poplar trees that looked too beautiful, documenting it all …”

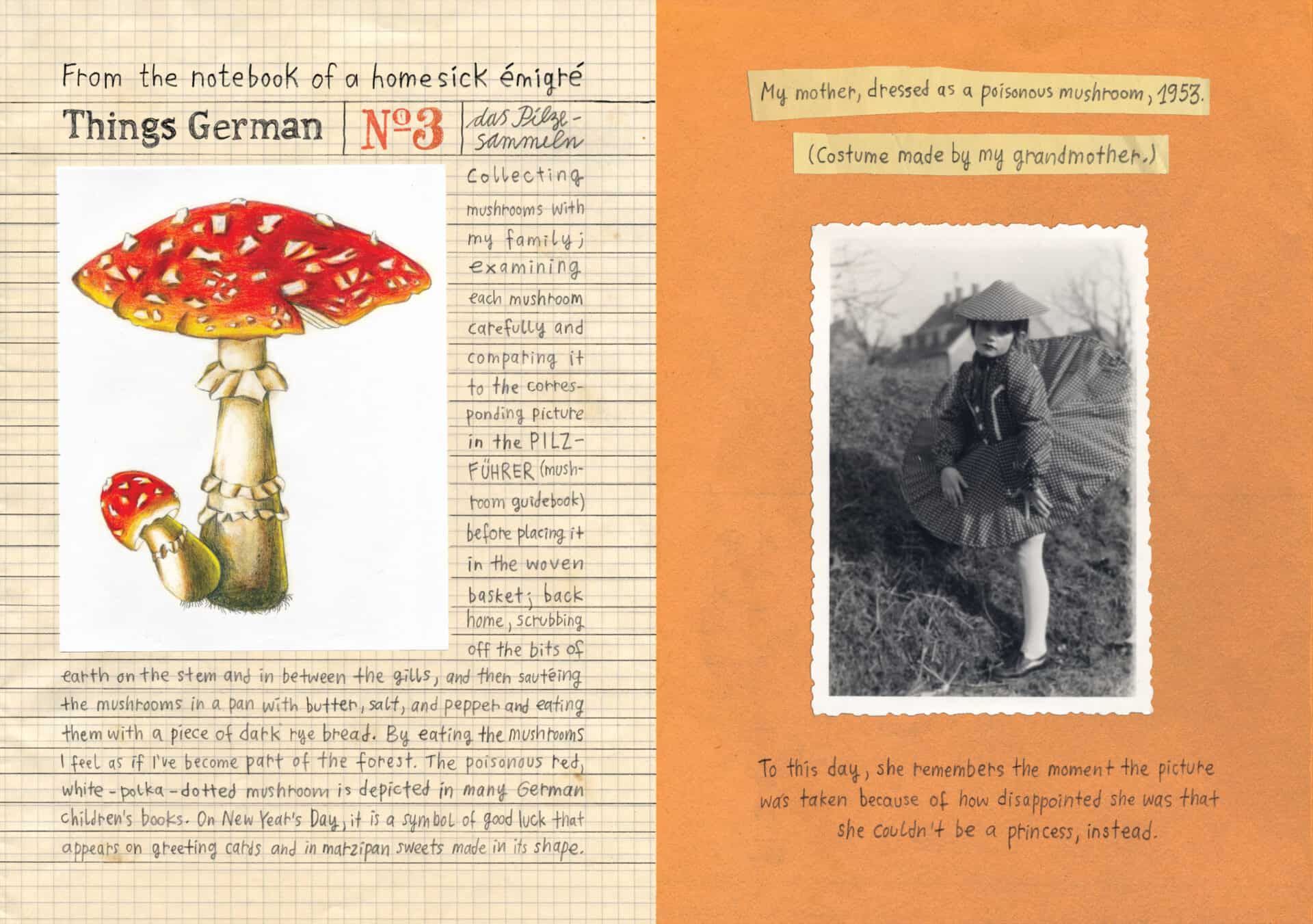

Growing up in Germany, Krug felt the weight of that past. Her schools and teachers led her and her classmates into detailed research on political figures and national movements, she said. But she had never talked with her own grandparents about their experiences in World War II. Her teachers never asked her to, and her family would never talk about that time.

Uncovering the stories behind their silence, years later, she would write her first full-length autobiography, not to deny or downplay or erase pain her country has caused and carried, but to try to understand it, and then to counteract it.

Krug is now a German American artist, writer and historian living in Brooklyn, N.Y., and she spoke on Saturday as her new art retrospective opened at the Norman Rockwell Museum — drawing in her graphic memoir, Belonging: A German Reckons with History and Home, winner of the National Book Critics Circle Award.

Around her own stories, she also explores her illustrated version of Timothy Snyder’s On Tyranny: Twenty Lessons from the Twentieth Century — guidelines for identifying, surviving and resisting authoritarianism in America and throughout the world.

Nora Krug, a German American author and illustrator, examines structures that lead to extremism — and people who resist them. Press photo courtesy of the Norman Rockwell Museum

She works in a style of scrapbook and commentary and collage, so that often she is shaping her stories not in one often linear narrative but along a network of branching lines. She deliberately opens to many perspectives, and her voice and mix of sources can have the informal style of social media.

Research overlaps with memories and thoughts in the moment. Images and memes move across space and time, as though the book has the effect of hyperlinks.

In her own work, she explores archives and flea markets, gathers interviews and oral histories — and brings them together with drawings, papercuts, photographs.

As she was when she visited memorials with her camera in high school, she is still trying to understand the scope of atrocities committed, not only in World War II, but in the past and today, around the world and in the U.S., where she lives now. And as she was then, she traces evidence of collective guilt, and its effects on future generations.

‘How do you know who you are if you don’t understand where you came from?’ — Nora Krug

A weight of national shame can lead to paralysis, she said in her talk, as though when the whole country is at fault, the scope of the problem becomes overwhelming, too much for any one person to make a difference. She doesn’t let anyone off, very much including herself.

But in her reckoning with individual stories, she finds new ways of thinking, not only about her country and her family, but about her own life and her future. Grappling with the past has helped her to find a new kind of confidence in her ability to act.

“How do you know who you are,” she asks in her memoir, “if you don’t understand where you came from?”

She wants to replace a sense of guilt with a sense responsibility, she said. So in her research and in conversations, she works to understand and fill gaps in her knowledge.

Nora Krug, a German American author and illustrator, examines structures that lead to extremism — and people who resist them. Press photo courtesy of the Norman Rockwell Museum

Growing up, she had never learned about contemporary Jewish culture, she writes in her memoir. She had no knowledge of the Yiddish language, of centuries of Jewish presence and tradition across Europe, or of experiences and innovations and accomplishments today.

She would learn about decisions her relatives made during the war, some of them hard for her to face. She would also learn elements of war history that surprised her, that her school teachers had never begun to touch on.

“We didn’t learn that tens of thousands of Germans had been killed for resisting the Nazi regime,” she writes, “(because it would have made our grandparents who didn’t resist look guiltier in comparison?) … ”

She hadn’t known that 150,000 men of Jewish descent had fought in the Wehrmacht — she hadn’t learned about German losses endured during allied bombings, or about millions of Germans displaced from Germany’s former eastern regions after 1945.

‘Images have political power, and they can change the way we think.’

Clarity runs as a current runs through her work in this show, feeling sharply timely today — the importance of knowing accurate information from misinformation. Artists need to take responsibility, she said, for the images they create (and remix) and the stories they hold.

Those images can encode and preserve ideas, sometimes for centuries. Some can be troubling, as she revealed in the talk, tracing images from 1930s fascist propaganda back to Martin Luther. And some can be liberal, nuanced and expressive.

“Images have political power,” she writes in the show, “and they can change the way we think.”

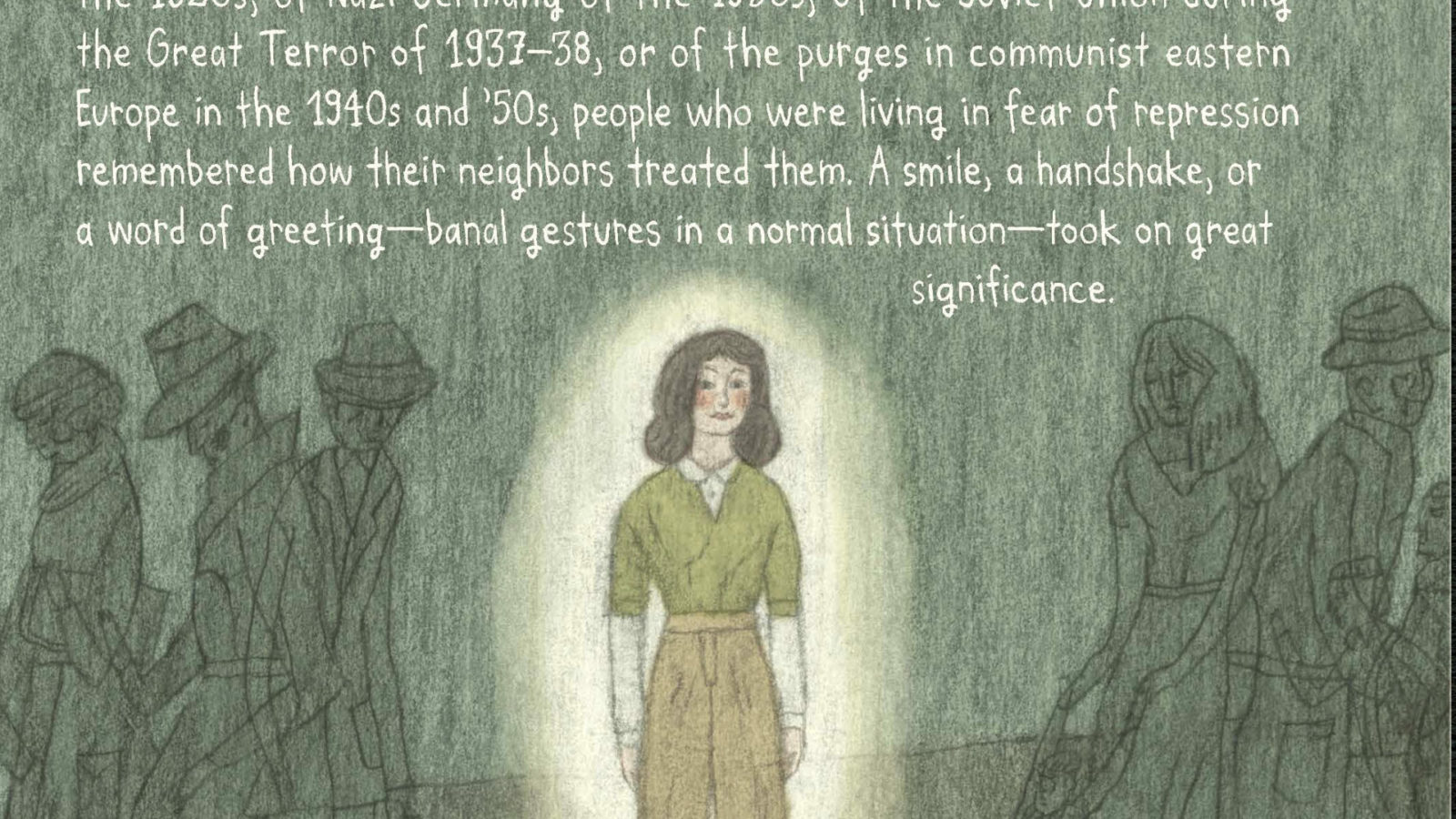

Tracing her country’s past in the 1930s gives her an insight into the rise of fascism, and she can recognize some of the same disturbing patterns when then appear in other places, including in the country where she and her family live today — here.

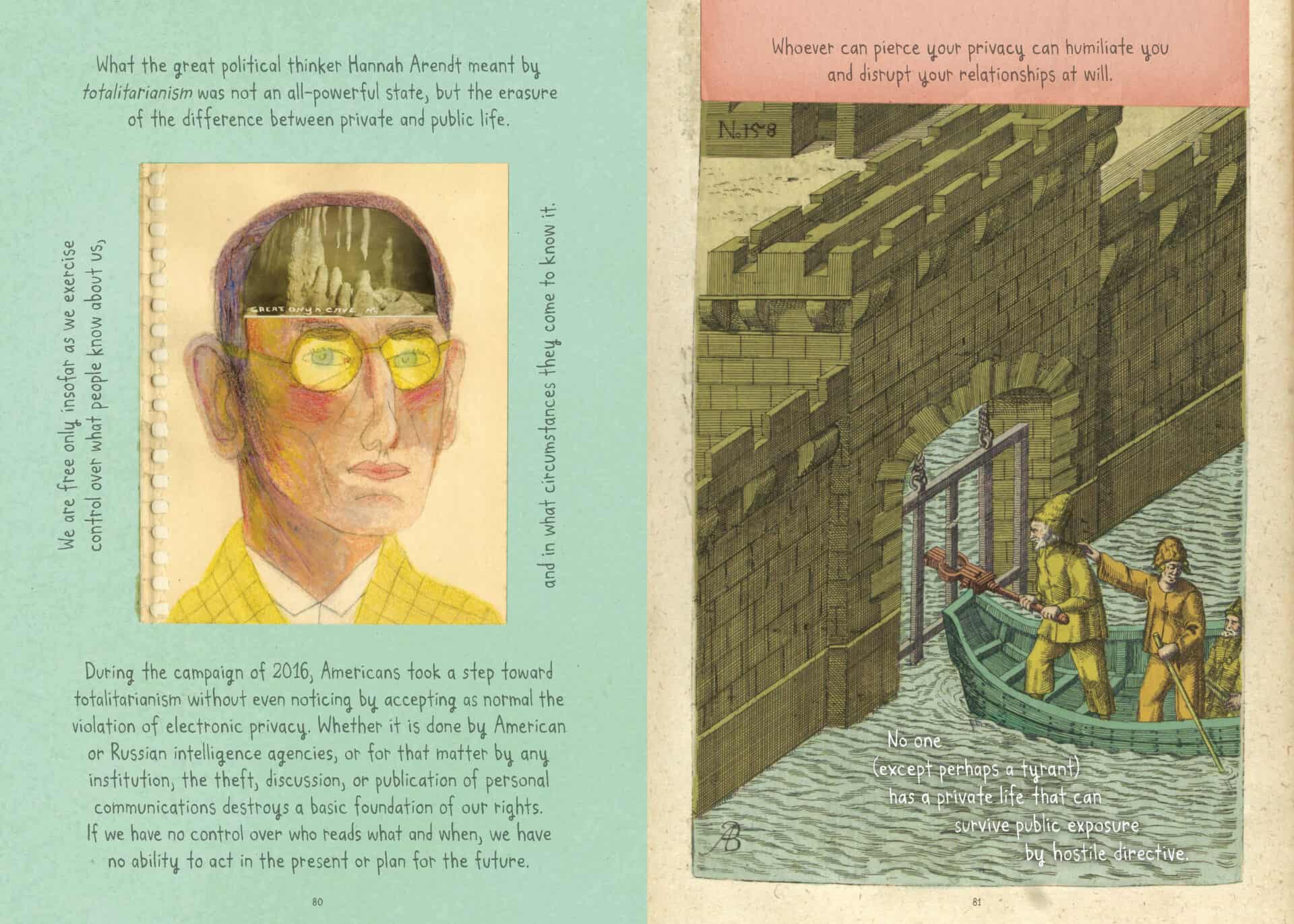

And so she brings those lessons into Timothy Snyder’s guide to ways to stand against hate around the world today. He offers 20 principles to live by, each one drawn from events and experiences in the last century, and relating for him, and to her, intensely to what’s happening in this country today.

Take responsibility for the face of the world. Protect the boundary between public and private life. Don’t obey or allow repression without thinking …

As she expands around his ideas in many directions, in historic photographs from many parts of the world, drawings, symbols, real examples from the lives of dictators — and more importantly for her, people who have stood for humanity and courage — Krug begins to explore ways of thinking she had not known when she was younger, or had not thought she could claim as her own.

“We learned that our language was once poetic but now potentially dangerous,” she writes in her memoir.

Remembering the trees and fir cones and rivers in the Black Forest, she recalls there that the Grimm brothers once claimed their German dictionary, begun in 1838, lists more than a thousand nouns and adjectives including the world wald, woodland. Waldeinsamkeit means forest-solitude. Waldfinsternis means forest-obscurity, and waldumrauscht surrounded by a rustling forest.

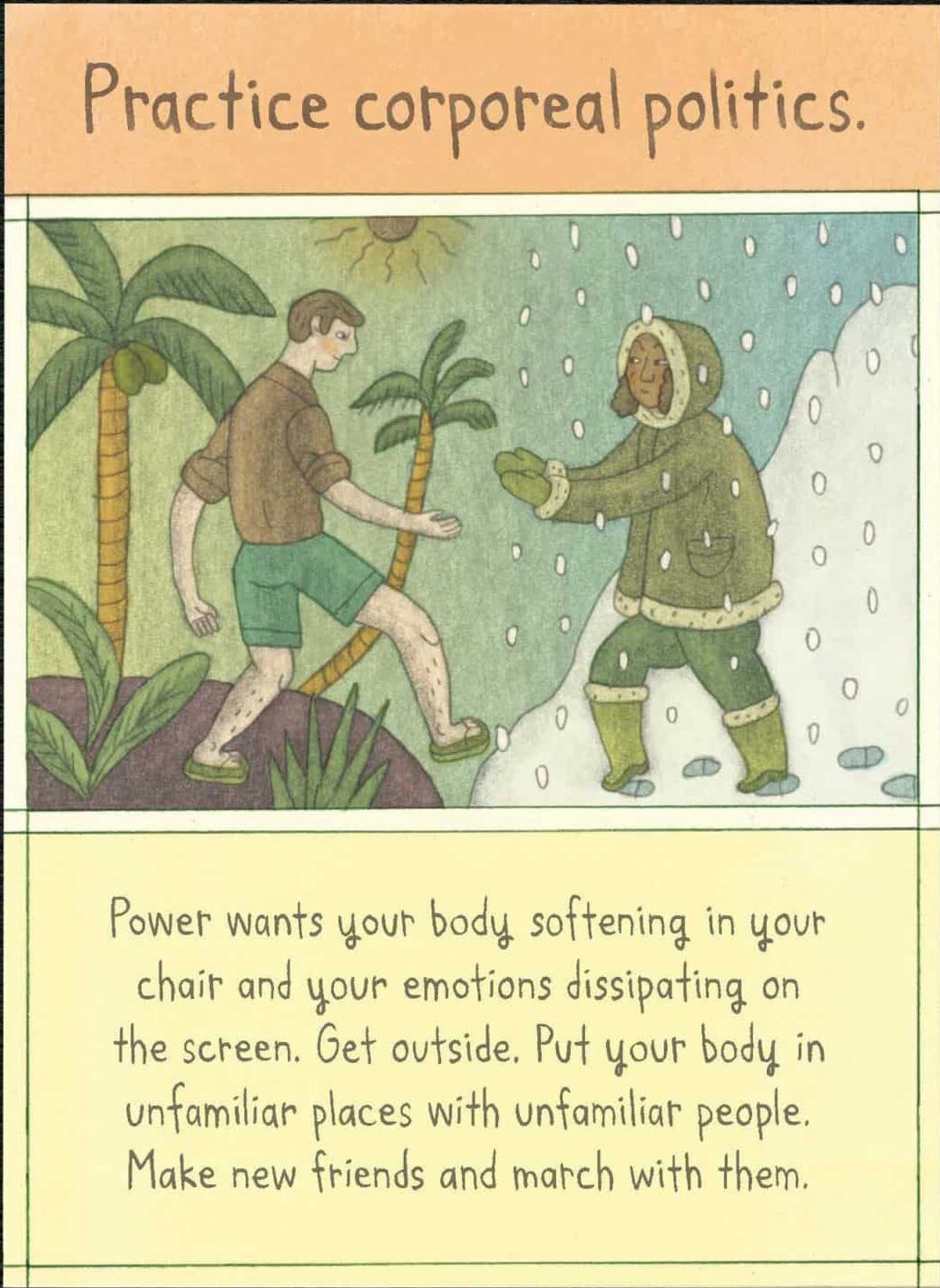

Looking at her memoir and her manifesto here, side by side, her memories of the land where she was born seem to weave naturally into Snyder’s principal of living with a tangible body. He urges people to build confident collaborations, debate ideas about change with people of various backgrounds who don’t agree about everything.

“Get outside,” he writes in the show. “Put your body in unfamiliar places with unfamiliar people. Make new friends and march with them.”