On an August afternoon at the Old Stone Mill in Adams, Leni Fried and Mike Augspurger were outside by the Hoosic River, tye-dying aprons with Pauline Dongala and Josephine Moundouti. They built a fire outdoors and heated the dye over it, and coated the pot in mud to keep the flame from darkening the metal.

Paintbrushes stand in bright colors in the print shop at the Old Stone Mill in Adams.

Fried listened as they talked about the dye plants they have known since they were children and the villages where they were born. They remembered gathering with people, cooking over a fire and dreaming.

Here in at the mill they cooked potatoes in the embers while they hung the aprons on a clothesline to dry. They were making patterns in deep greens and smokey blues, teasing art and play out of linens a local company would have thrown away.

Dongala lives in Great Barrington, and she has been working with the Old Stone Mill Center for Arts and Creative Engineering to send daily necessities to the community in the Democratic Republic of the Congo where she once lived. She sends bicycles so children can get to school, sheets for hospital beds — goods they sorely need and people here were ready to toss out.

Moundouti lives in Burlington, Vt., and she has led her own nonprofit in the Congo for 10 years. She learned about the Old Stone Mill’s partnership in a Youtube video and reached out to them.

And Fried and Augspurger look back to that night as they explain how two artists from Cummington came to buy an old gutted woolen mill in Adams and give it a new purpose. Connections like this are what the Old Stone Mill is made for.

Upcycling on a wider scale

Fried and Augspurger took on the Old Stone Mill in Adams in 2016, and they are growing it as a Zero Waste Maker Space.

She is an artist and printmaker, and he is a metalworker — while she is making monotypes and linocuts in her studio in their roomy old barn in Cummington, he is repairing and reconstructing bicycles, including many adapted for people with disabilities.

Here at the mill, at the core of their mission, they take in surplus from local sources and find new uses for them, to keep them from ending up in landfills.

Brought into the sunlight, the amounts they are finding become quickly staggering. Every year, Fried and Augspurger take in thousands of pounds of used sheets, blankets and chef’s shirts from just one local company, Aladco Linen Services in Adams. The cloth adds up to 15 tons a year.

Aladco supplies linens for Williams College, local restaurants and hotels and more. For 25 years, Augspurger said, whenever anything became even slightly torn or stained they would send it to the incinerator.

In its six years of operation, mill has taken in more than 90 tons of cloth that would simply have burned. And they have gone to beds for people who have become homeless and rooms in a hospital ward in Honduras — they have helped people here in the community and around the world.

In concrete programs like this one, Fried and Augspurger say, they want to look toward the future with sustainability and creativity, practical skills and resourceful energy.

A fleet of repaired and repurposed bikes fills an upper floor at the Old Stone Mill in Adams.

The roots of change

The vision tool root some 20 years ago, Fried said. They were living in Cummington by then, and their small hilltown has the kind of community that sustains the Old Creamery co-op market and coordinates an annual seed and plant swap in early spring where locals bring offerings they have transplanted from their gardens: raspberries, crimson beebalm, hyssop smelling of anise.

Among their neighbors, Fried and Augspurger started a sustainability group. Friends would come together and talk about how they wanted to live and shape the future.

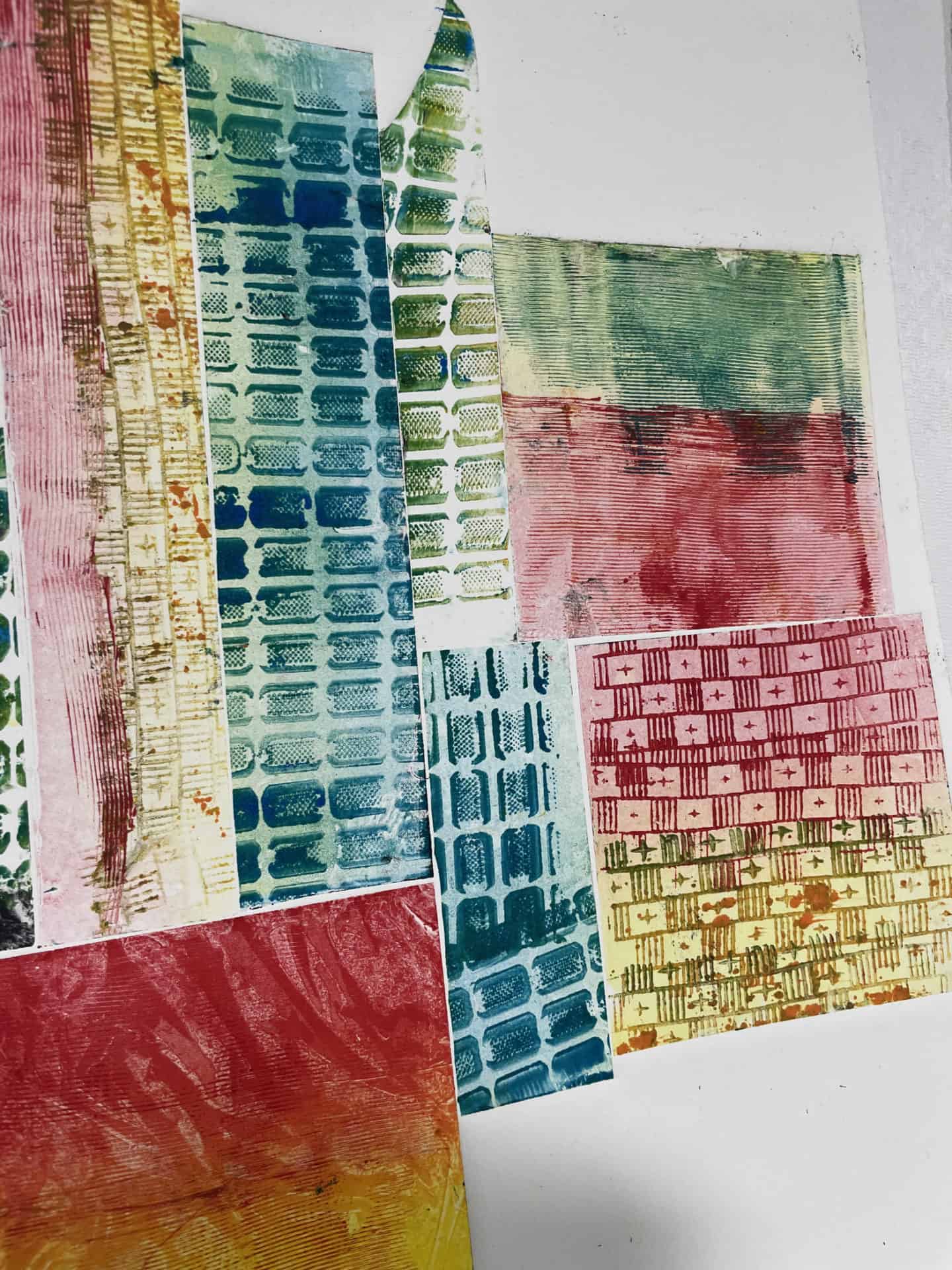

Prints made with repurposed bike handle grips show vivid color at the Old Stone Mill in Adams.

“We had meetings for months,” she said. “We watched An Inconvenient Truth and talked about climate change. It was amazing really.”

They shared books and documentaries and resources, Fried said, and the philosophy and research that emerged in those conversations still guides their work.

“What we’re doing now is building the root system of this building,” she said. “It’s more than 160 years old, and it will outlast us. We’re trying to project about the future. And we’re not in a hurry.”

Remeasuring what we make

In her print studio in Cummington recently, she has been working on an image that encompasses that sense of the world. She printed the spiral of a snail and found herself thinking — snail’s pace lightening fast.

In part she means that the systems they are putting in place can grow gradually over time and then have the capacity to move fast, as they find and build resources and then find someone who needs them.

And and in part she means that she and Augspurger take the time to see what they have around them and think about how they can use it.

“We’re accelerated because of the things we use,” Fried said. “Technology accelerates us.”

‘We’re accelerated because of the things we use. Technology accelerates us.’ — Leni Fried

She sees people focused on instantaneous decisions, spending less time in looking around and looking closely. And she finds value in that kind of attention, and plain fun. She and Augspurger show the results they have gathered around them with humor, as practical as a drill press and as imaginative as an obstacle course or a treasure hunt.

As they find and trace streams of goods, they look at what people in the community are making and buying and disposing of. Fried looks at the pressure of continuous manufacturing, and she talks instead in terms of a conscious, rooted energy. She sees it as the inverse of a tree that grows for a hundred or a thousand years and then gets cut down in a day.

“We need perspective,” she said. “The way Mike’s doing with his metalwork workshop — (he’s teaching them how to measure,) because no one knows how to measure now, even how to use a ruler or a tape measure. These are life skills that we don’t develop because we don’t need the, and they’re important.”

“… We’re at an extreme. We throw so much away, and we don’t notice. We don’t revere the earth we’re part of.”

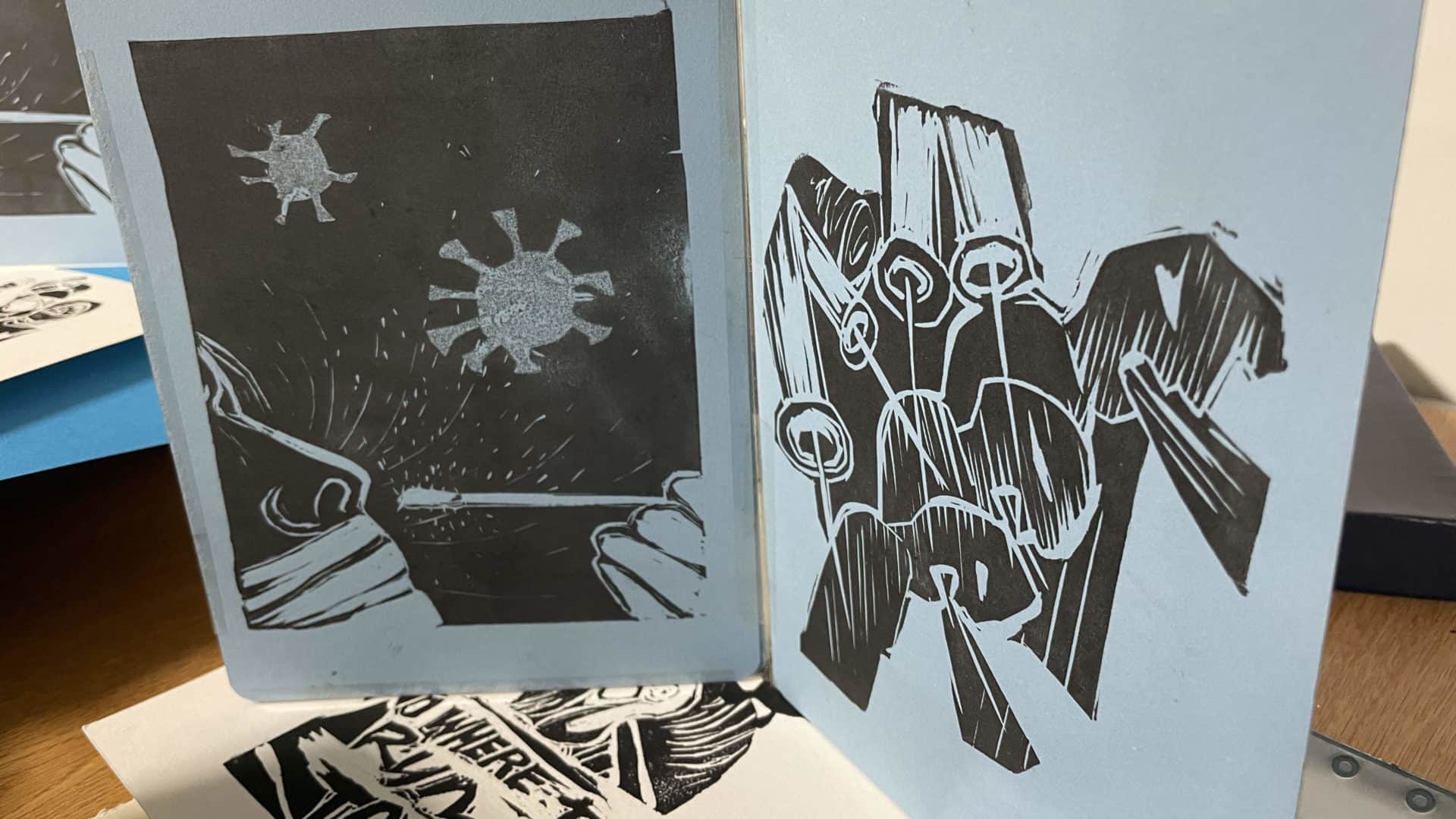

Leni Fried's images explore experiences from the pandemic in the print shop at the Old Stone Mill in Adams.

How goods come into the mill

And so, in a c. 1860 building that originally manufactured Union soldier uniforms, she and Augspurger now have stacks of table cloths and hospital scrubs, and bolts of cloth donated from people in the community. In the front hall, they have remade grain sacks into storage bags.

Open spaces are full of projects and windfalls — a grain grinder run by bicycle stands near cotton batting from hundred-year-old church pews. They stripped away the old, worn fabric and found the seats filled with real cotton, Augspurger said. And now they have 30 bales worth.

They are well-known enough now that people often call them in, he said, and they often hear from people who haven’t had the time or taken the responsibility for planning. A school in Springfield closed because of tornado damage. A company shut down that makes office furniture.

That adventure left the mill with 90 conference table tops, Augspurger said. He turned some of them into tables for a new café coming into the Adams Theatre.

“When a company goes out of business,” Fried said, “what happens to what they’ve bought?”

‘When Crane & Co. moved, they had 30 palettes of paper, and they had to clear the warehouse in a week.

She opens drawers full of vividly colorful paper from Crane Co. in Dalton. When the factory moved, she said, they told her they had 30 palettes of paper, and they had to clear the warehouse in a week. They meant to recycle the paper, meaning in the best case scenario, reams on reams of high-quality paper would be chopped up and repurposed into — more paper.

Fried thought she could find a more efficient and useful alternative. She recalled a friend talking about the conservation of previous effort, and she wanted to respect the resources that had gone into making this beautiful paper.

She asked Crane if they could wait two days, she said, to give her time to spread the word, and they agreed to open the warehouse for three hours on that Monday and Tuesday. She posted to Facebook and got thousands of hits — and people came. Teachers came from as far away as Vermont. People came in trucks and trucks and cars and trailers. And in two days the warehouse was clean.

Leni Fried leads a printmaking workshop shop at the Old Stone Mill, and Michael Augspurger leads a metalwork workshop.

And good comes out of the mill

When goods come into the mill, Fried and Augspurger have the space and time to store them until they can find people who need them. Some they keep in the Maker Space for remaking, repairing or redistribution — and many they send to local shelters, youth centers, local health and creative centers, schools, camps, art studios and gardens.

“Our surplus is their scarcity,” Fried likes to say.

They are collaborating now with three or four people who fill shipping containers for communities in the Congo and Honduras and hospitals on the Ivory Coast.

Moundouti has told Fried that in her former home in the Congo, a company from China has bought the land surrounding the village, where the local families used to grow crops as their only food source, so now the adults have to walk 25 miles to the fields they cultivate, leaving their children.

She has sent them bicyles from the Old Stone Mill, and also parts, pumps, tire irons, the inner tubes from the tires, encouraging them to learn to make and repair their own machines.

Fried looks at photographs on her wall of people who have piled their bycicles with grain sacks in stacks twice a man’s height, and she reflects on how highly people in one place can value something people in another place scarcely notice.

For the first five years, she said, the mill gave away everything they gathered, completely free. As the amounts they handle keep growing, and the amount of time grows with them, that model became unsustainable, and she and Augspurger now sell those goods at very low cost in ways that do not compete with the places that have donated them, or they coordinate with organizations in their sphere.

“I used to spend hours on the phone talking with Shelters and Springfield Rescue,” Fried said.

Now the mill works with Helpsy, a socially and environmentally conscious clothing recycling company who helps with the volume of sheets and blankets they take in. (They also have Helpsy recycling bins for clothing out front, accepting clothes and shoes people want to offer any time.)

People in the maker space

And now, more and more, in quiet ways, they are reaching out to the community around them. In a front room with high ceilings, tall windows and a wood floor they hold open studios with Fried’s cards and prints, which she also offers now at the Mass MoCA shop.

They have visions of this room filled like the Boston Children’s Museum with barrels of found oddments for art projects, polished wooden spheres, scrap metal, glass and more for imaginative play and art.

Right now, anyone in the community is welcome — by appointment — to come in and look around on their own. Fried calls this a makers market. You can come in and pay for a bag ($3 to $10) and simply fill it with anything you see.

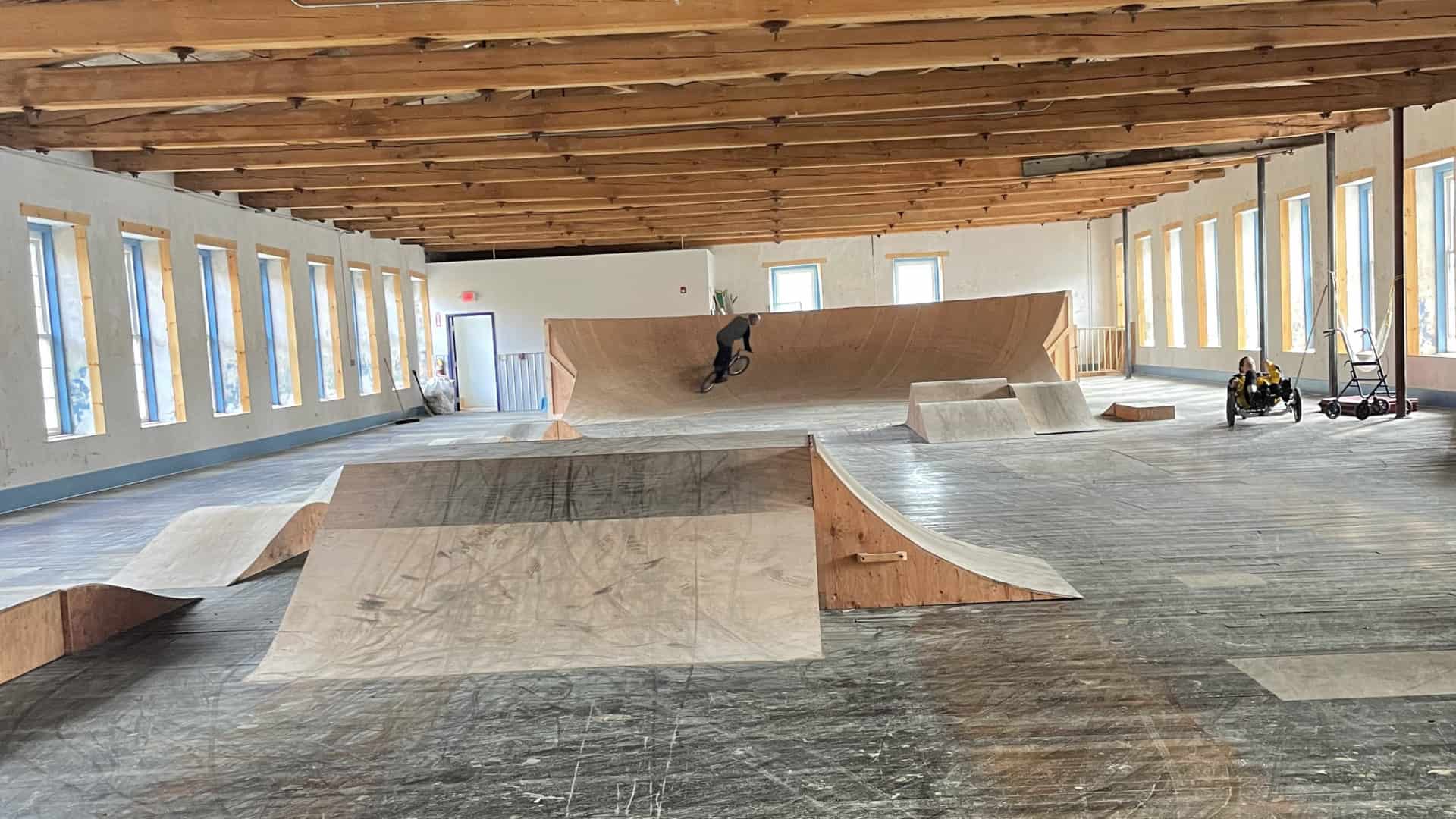

Michael Augsourger rides a bike though an indoor course at the Old Stone Mill in Adams.

The center room is busy with shelves of cloth and fabric, easils and cleaned paint brushes, wrapping paper, a collection of picture frames … Fried used to frame art and photographs, she said, years ago when she and Augspurger lived in Boston, and people so often throw frames away.

This fall, too, they have begun offering workshops in the makerspace. She has set up a pring shop on the second floor, and she is leading a group in monoprints and collagraphs and linotypes, all kinds of ways to create shapes and play with inks on paper.

One floor down, Augspurger is leading a class in his metal shop, and for their first project they are making rollers for Fried’s print shop studio out of the upcycled hand grips from bycycle handles.

Those grips have shapes imprinted in the rubber, and when they repeat, overlaid with green and red and gold inks, they can form patterns as bright as kente cloth.

The grip fits around a short piece of the bike’s metal handle bar, Augspurger explained, and turns around a thin bar of metal as an axel. He is teaching his workshop to make a wooden tube to fit between the handle and the axel. Then they repurpose old screwdrivers to become the handles of the rollers.

‘It has to be fun.’ — Michael Augspurger

He shows the spot welder, lathes, grindstone, milling machine — some of the machines in his workshop he has made and adapted, himself. For years he made titanium wedding rings, he said, as he showed a teal blue band shaped from the outer casing of a bowling ball. But chiefly he repairs bicycles, including bikes for sale to support the mill, as he has for 40 years.

“When they invented mountain bikes,” he said, “about 1981, we were living in the city. I used to race motorcycles, and I couldn’t do that there. But I loved mountain bikes, sturdy bikes with flat handle bars … I started working at a place in Somerville that made them.”

Out here, even on a rainy fall day, he can still casually pop a wheelie and skim up a ramp half the height of the mill’s double-storey walls. The top floor of the mill is an open space right now, full of bike jumps and a motley crew of wheels.

“It has to be fun,” he said, laughing.

He has made and repaired unicycles, reclining tricycles, scooters and bikes of all sizes. For four years, before Covid, he and Fried partnered often with a local youth center. He has swings up here, hanging from the beams, and rings and a kind of bouncing bar hanging from a spring. Hold those handles and you can let the spring take your weight and fall freely into the air.

Michael Augsourger rides a bike though an indoor course at the Old Stone Mill in Adams.