In a well, in a stone, in a library, we have some of the first human writing — someone recorded thoughts and ideas on bone 4000 years ago, in the Shang Dynasty, and set them in fire to understand the future.

For Elizabeth Atterbury, they tell stories about family. An artist in Portland, Maine, she has brought Oracle Bones to the Clark Art Institute this year, and in an artist talk this fall, and in conversation by phone afterward, she talked about the origins of her sculpture in wood and cloth, metal and stone, and her abstract prints in bright color.

As a child, she often spent time with her mother’s parents, she said. Growing up and into her teenage years, she would rest in their apartment in Southern Florida. She recalls clear familiar details, Chinese ink scroll paintings on the walls, a towel folded on the back of the couch. The rich scents and spices of her grandmother’s cooking made her feel welcome and warm. (And someone living nearby complained about them — she remembers that too).

Elizabeth Atterbury recalls her grandmother's fan in an arc of cherry wood as tall a woman, at the Clark Art Institute.

As she talks about those times and quiet rooms, they hold a sense of beautiful discoveries hidden and revealed. Her grandmother wore her hair rolled smoothly into a bun.

“I thought it was like a secret,” Atterbury said. “She would say, ‘only tell people half of what you know.’”

Together they would open drawers and cabinets, and she felt a sense of adventure. She would find photograph albums, cassette tapes named in Chinese characters, jewelry, “a library of colors and patterns.”

Then her mother died, when she and her sister were young. And not long afterward, she lost her grandmother. Her grandfather lived eight years longer, and they stayed close. She and he and her sister traveled together. She talked on the phone with him every day.

And so her artwork has grown from a sense of loss, she said. In her work, objects often become repositories for family stories.

Elizabeth Atterbury’s sculpture in wood and chin collé abstract prints appear in Oracle Bones at the Clark Art Institute.

Here in the open reading room of the Manton Center, she has set two fans as tall as a woman, made from cherry wood. One is folded closed, and one opens out like wings. She drew inspiration from her grandmother’s fan, with paintings on silk of mountains and willow and cherry blossom, and two figures rowing a boat on the water.

Closed, the colors compressed, she said, as though they could form another image any time she opened them, and the fan took on the shape of a person.

She enjoys working in these larger forms, she says. Their scale and time has helped her to slow down, to think while she is making. In her woodshop in Maine she makes drawings, sifts through pieces of cedar from a home projects, pieces together different kinds of wood for models.

“They’re all hand-cut, each piece,” she said.

‘They’re all hand-cut, each piece.’ — Elizabeth Atterbury

She chose cherry for these because the wood can darken and resemble the wood from her grandmother’s fan. She worked with a friend to resaw the boards and a fabricator to shape fine slats for the ribs of the fan, and she sanded, shaped the cloth and finished the wood by hand.

In her small, rural city, she enjoys exploring for materials and getting to know her neighbors at the lumber yard, at the hardware store. She has met a stone supplier north of Portland who has a remnants pile. She found blocks there, she said, pulled from Boston Harbor — remainders that once supported a bridge across water, and space and time and geography.

Here beside the fans, the stone now holds the story of a family member she has never had the chance to meet. Her great great grandfather, Wang Yirong, was the scholar and calligrapher who first recognized oracle bones for what they are.

Elizabeth Atterbury's sculpture in raked mortar over wood she calls 'Who am I if I am not from you, did you seek me, did I reach back?' at the Clark Art Institute

4000 years ago, in the city of Yin, the last capital of the Shang dynasty (a city whose name means vibrant music-making), people would write characters on ox bone or tortoise shell. They used the bones for pyromancy, divination by fire.

Her great great grandfather saw one for the first time at an apothecary, she said. As she has heard the story, someone in his household was fevered with malaria, and he went to find medicine. At the time, the apothecary would have ground these bones as part of the preparation. Her grandfather’s grandfather saw the inscriptions and recognized them as calligraphy, and he preserved them and studied them.

His scholarship lasted only a year, Atterbury said, before the Boxer Rebellion cut short his work and his life. She has tried to learn more about him — she studied Chinese in college, and when she studied abroad, her grandfather came with her. She wanted to do research in the museum in her grandfather’s grandfather’s hometown.

‘I have been thinking about identity and authenticity, and defining for myself what that relationship is.’ — Elizabeth Atterbury

But though she has studied the language and lived in the country, she would need more fluency to have conversations in depth and read books about her great great grandfather’s work. For her mother, she said, Chinese was her first language in New York, but Atterbury did not have the chance to learn the same way.

But she has held an oracle bone in her hand. Some years ago, she showed work at the Colby College museum, she said, and after the show she got a package in the mail — someone seeing her work had been given oracle bones and wanted to find a way to return them … and sent them to her.

And now they’re here, sealed in a chamber in the bridge stone. She has shaped the stone to suggest the form of a chop, a handheld seal, and set those ancient words invisible in its heart.

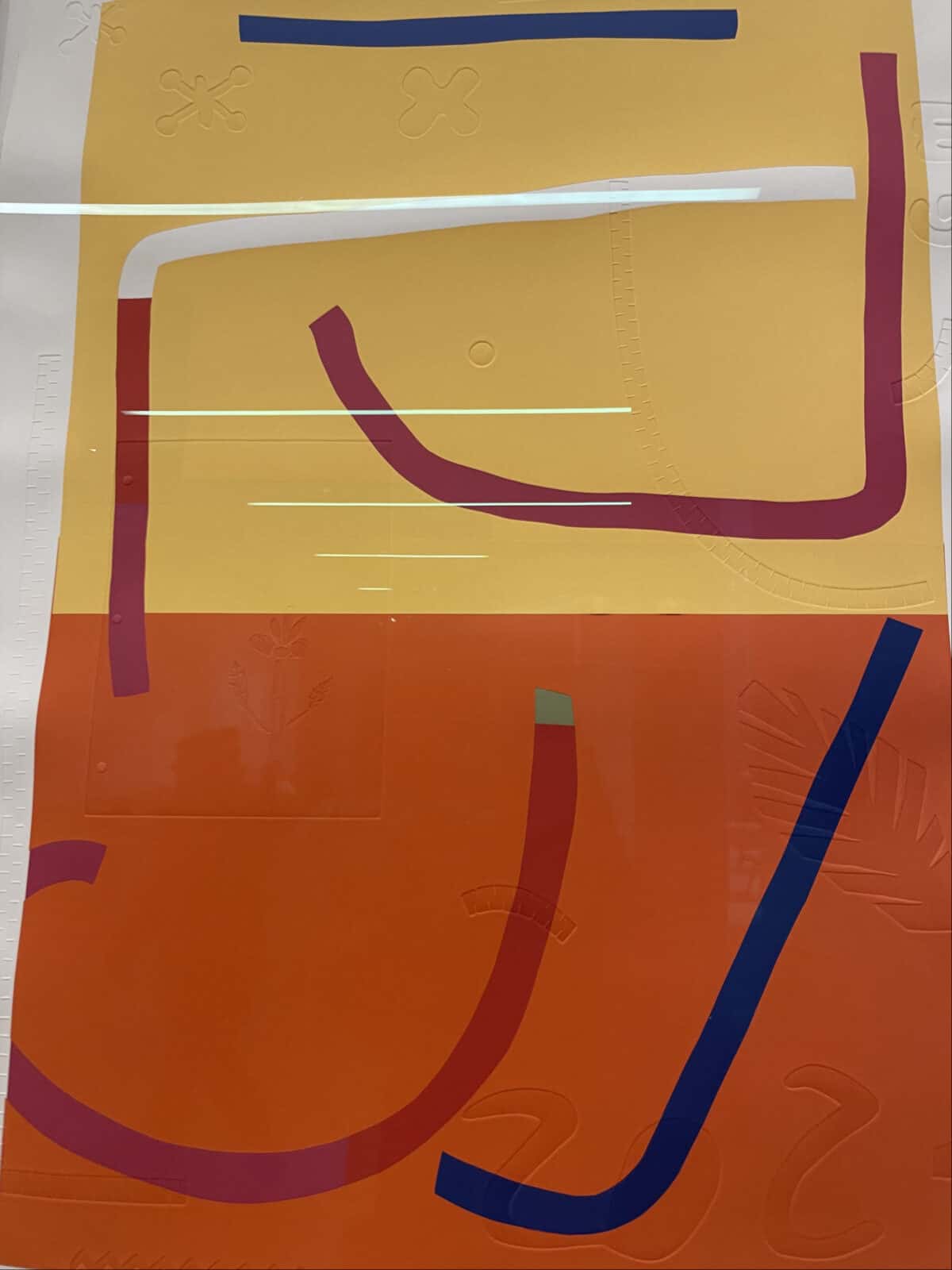

Elizabeth Atterbury shows embossed prints in vivid abstract color at the Clark Art Institute.

She finds the bones both beautiful and vast, she said, as she feels close to them and also in a way distant. As a woman with heritage from more than one culture and part of the world, she feels the loss of loved ones, and the loss of almost half of her family tree.

“My mother is an only child,” she said. “… I have been thinking about identity and authenticity, and defining for myself what that relationship is … and at this point in my career, understanding and clarifying and being comfortable sitting with these questions, rather than saying ‘I’m making a work about identity’ — it’s bigger than that, more universal.”

‘With photographs there are too many barriers. I felt disconnected from the present, and I wanted to make something with my hands.’ — Elizabeth Atterbury

And she has found common chords across time and distance. Talking with a friend from graduate school, when she was working on one of her human-sized first fans, she learned her friend’s grandmother in Mexico also used to have a fan — she would carry a large and generous bag that held only her fan and candy to give away.

Atterbury finds warm ground to stand on, in that kind of meeting place with someone in another country. She has come into sculpture in part for the feeling of connection, she said, and physical touch. She had studied photography in graduate school.

“With photographs there are too many barriers,” she said. “I felt disconnected from the present, and I wanted to make something with my hands.”

Making prints or ceramic tiles, she can feel at one with human beings shaping paint and paper and clay like this across the world.

She was making these vivid prints when Robert Wiesenberger, the Clark’s curator of contemporary projects, came to see her to talk about the Clark show. He watched her making them, embossed with copper plates that imprint shapes into the ink and paper.

‘They’re a form of interpretive writing, nonverbal poetry, private notes to myself, and I hope people can feel curious about them.’

She collected ideas for these copper shapes from home and family, she said. One comes from a drawing of her son’s. In a print she made on her sister-in-law’s birthday, she found shapes for her initials, and for shared memories. They both grew up in Florida, so a curve suggests palm leaves.

Another, rounded and pointed, invokes jacks (the game), from a summer when they went to a camp in Maine together and played jacks in their cabin bunks. Her sister and sister-in-law live in South Portland, she said, and they are all close, so for her, these shapes tell a direct story.

In some prints, as in her sculpture, the shapes become more abstract.

“They’re a form of interpretive writing,” she said, “nonverbal poetry, private notes to myself, and I hope people can feel curious about them.”

She began one of the earliest with the stroke of a curved line, she said, like the a silhouette of an open fan.

This story first ran in the Berkshire Eagle in fall 2023 — my thanks to features editor Jennifer Huberdeau.