Trinh Mai Thạch and her husband, Hien, are walking on the beach in Southern California.

They bring home smooth stones and driftwood from the tideline. Among the rounded pebbles on the shore they realize three white and grey mottled curves close together are the shells of a piping plover’s eggs.

Shann Ray Ferch and his wife, Jen, hike in the high meadows in northern Montana.

He was walking in the Beartooths recently with his father, he said, on a morning thick with frost, and they found the bones of an elk fanned across a field. Sometimes an elk will die in winter, he said, and porcupines will clean the bones.

In the living elk the antlers would have spread seven feet wide. And he has heard male elk calling in their full display.

“Elk bugling is ethereal, like a trumpet,” he said. “And there are a ton of them, because they’re in rut, bugling across a massive valley. And the sun comes above the rocks and floods the valley. It’s like walking in an upside down sky. The frost is diamond-lit as it’s melting.”

Ray is a poet and traveler, professor at Gonzaga University and winner of the American Book Award. Mai is a nationally recognized artist, and this fall she is working with Massachusetts College of Liberal Arts on their Hostile Terrain 94 project and bringing her work across the country to a group show at MCLA’s Gallery 51 this winter.

Together she and Ray have created a book of words and paintings and photographs — Atomic Theory 7, Poems to My Wife and God — asking how to understand a world where the beauty of the high canyons and the daily touching of a loving marriage can exist at the same time as blood and death.

Paradise Valley, near Livingston, Montana, gleams golden in the sunlight. Photo courtesy of Shann Ray.

They both have an intimate connection with this tension and balance.

Mai’s family has come to America more than a generation ago from North and South Vietnam, and she holds their stories in her art. Ray’s family has Czech and German roots, and he has researched genocide around the world.

He focuses on people who have endured immeasurable pain and the ways they stand in their strength and hold authority in reconciliation and resilience.

In Atomic Theory 7, he comes back to them in cycles of poems, moving from early dark to dawn and through the day, toward night.

The book is a project of poems held by fracture, Ray said. He writes in a language of particle physics, macro and micro to the minutest degree. Fission and fusion are always at work, he said, and the difference between them is exponential. The power in fusion, in unification, is challenged and continually returns.

“There comes a beautiful haunting,” he said, “and you reside in that and let it meet you and carry you.”

He first saw Mai’s work on the cover of Ruminate Magazine, he said. Inside the journal, the editors had set her artwork beside his poems. He felt a rugged humanity in her work. Even when they probe raw war wounds, he said, her paintings are rooted in a loving tribute to family.

He felt a connection between his work and hers.

“It’s a gift of her touch in the world,” he said.

She creates beauty from the most aggressive things.

“And you feel peace,” he said. “It is a profound generational gift in her family.”

So he wrote to her, asking if they might work together.

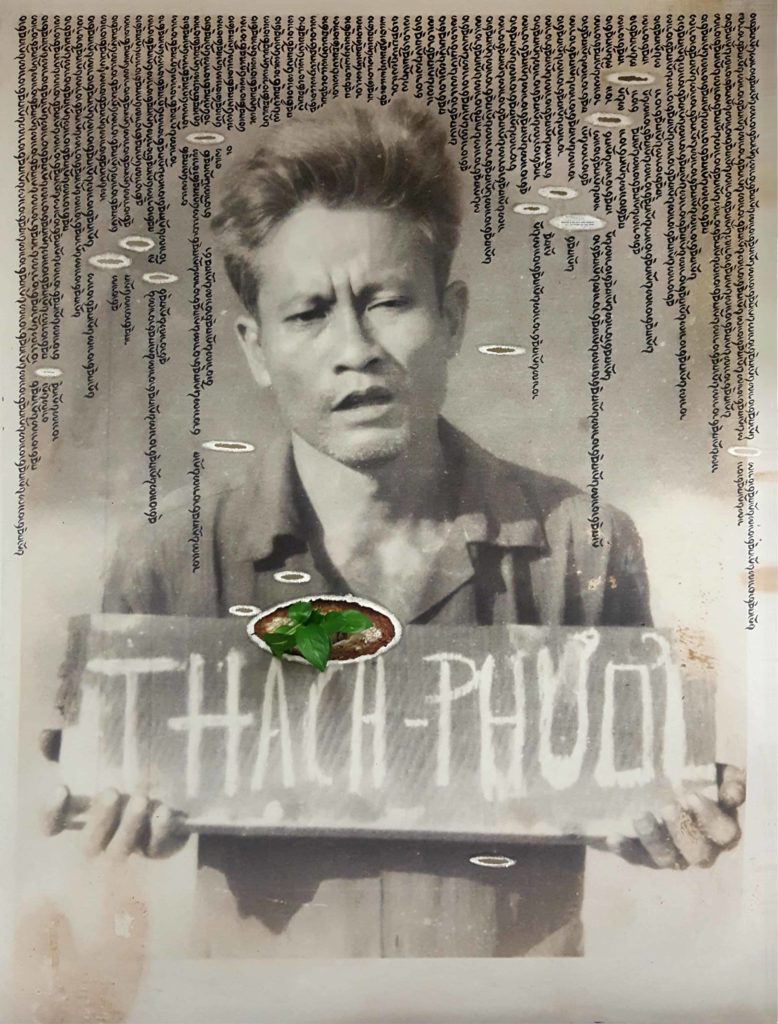

Artist Trinh Mai creates a work centering around a photograph of her father-in-law when he was a prisoner of war in Vietnam. Image courtesy of the artist.

His writing felt alive and vital to her, she said, an offering of himself, with a deep sense of peace. When he sent her his poems to read, she needed time to absorb them slowly.

“The book was such a liberator from fear,” she said.

It became for her a place to reveal deeply personal stories. Toward the last pages, she includes Ba Ói (Dear Father), a work she has created from a photograph of her husband Hien’s father, Phơưl Vân Thạch. He looks steadily out of the frame, as though he is about to speak. His shoulders are squared, and he is holding a wooden sign that bears his name. When the photograph was taken, he was a prisoner of war in a re-education camp in Viet Nam.

He survived both imprisonment and battle, and the loss of his home, as he and his family traveled on foot through Cambodia and Thailand to reach the U.S., and through all of that upheaval he held a gentleness and strength that moves her.

It took her a long time to create this work for him.

“I lived with it for months,” she said.

She rubbed rain water and tears into the paper to invoke the 17 bullet wounds he survived in the war, and she created a kind of living history collage, with the enlarged photo at the core, copies of his release papers from the camp, palm bark and papyrus, the words Ba Ói in Sanskrit falling around him like rain, and in the largest wound the shoots of young living leaves.

And it took her longer to share this work, as it took Ray time, she said, to share the poems in this book.

“Both works are so intimate,” she said. “We were not ready to show them. And then it happened.”

As they talked, she and Ray found themes running between their work, she said, as they tell their stories in their own forms, of marriage and family, distance and loss, and connection across time and space.

Ray too has family dislocated by war.

His German grandfather and Czech grandmother married in New York City just after the German genocide began in what was then Czechoslovakia. How, he asks, can he describe their union at that moment?

“… They are two bodies in love, in humor, argument and dance,” he said. “Their whole lives, they’d hip-check each other. He needed her to tell him don’t be such a stubborn German idiot. She needed him to tell her, the Czechs love arts, but right now you need to think more linearly.”

Ray’s family stories have influenced his research and his travels, he said, and he is always conscious of being a white man, not wanting to tell others’ stories, and wanting them heard.

‘We can remind others of healing. … This work reminds me healing is possible and does happen.’ — Trinh Mai

Mai feels a meeting across boundaries in her own family. Her family comes from the north of Viet Nam originally, and Hien’s from the south.

As she and Ray laid out the book together, they kept finding convergences. Without planning, she said, they would set their work together and see patterns emerge.

Her painting, Gathering Light, shows a woman walking through the night carrying a pack basket on her back filled with specks of flickering light, like dandelion seed or fireflies. And on the next page, a new cycle of poem begins with two words: Early Dark.

Ray recalls the last poem in the cycle Before Dawn, closing: “o sister windbird brother fire is there anything more / beautiful than a woman leading the people in praise.”

And on the facing pages a woman in Mai’s Reaching for Things Unseen leaps with one arm lifted high, stretching upward into the light.

The poems and the artwork invoke an intense awareness of a divine being and force, encounters with a power larger than daily life.

Ray asks how to think about God in a world where people can enact such violence on each other.

“… in rwanda the croat serb siege when we beheld / hitler stalin mau and infinitesimal quarks the building blocks / of hadrons dead millions atlantic american slave / trade dead millions north african islamic slave / trade 35 million deaths low estimate the native american holocaust / much more than six million the jewish shoah palestine cambodia the congo …”

He thinks of the God of Rainer Maria Rilke’s Book of Hours, who appears as a distant mystery. This is not the God that Ray invokes. Ray and Mai speak of God in intense experience and close, compassionate relationship.

“No one has the right to say what God is or what God is not,” Ray said. “… God is love — God is an encounter with love. We don’t have the right to say that love doesn’t exist.”

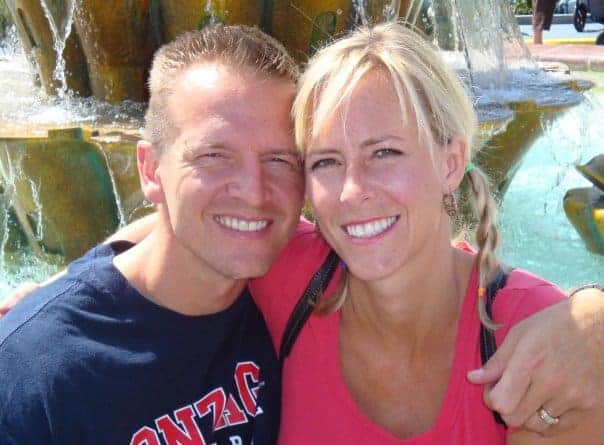

Shann Ray and his wife, Jenn, explore Montana together.

Rilke saw God as beyond understanding, he said. Rilke was harshly abandoned, and he abandoned his children. He imagines a beautiful, distant God.

Abandonment surfaces in Ray’s own poems, in the forces that shape dictators and holocausts — “fatherless fathers are marching …”

He grew up in a fatherless family that has later became more unified, he said. Being a psychologist, as well as a writer and a professor, he has seen how fundamentally a man or woman involved in trust and intimacy can draw lives and families together.

And so he says people should not blame their sense of God for violence, just as a man should not blame his wife and children if he has a troubled mind and causes them harm.

“We are responsible for love and forgiveness,” he said, “and love makes us more responsible.”

In this light, relationships become more free, autonomous, wise and healthy.

People ask “how could God let genocide happen?”

He answers, “We let genocide happen. We do this to each other.”

In his genocide research, across 30 years, he has made close friends around the world. People who have endured brutality will keep the memory of those events, he said, and speak from their own strength and integrity.

He has come to ceremonies at genocide sites worldwide. He remembers Lidice, a place that touches his own family history. In 1942, the Nazis were occupying Czechoslovakia against a growing resistance movement. In response to the death of a Nazi commander, they destroyed an entire town. They razed the village, in Central Bohemia, shot 173 men in one day and transported women and children to concentration camps.

Today the Lidice memorial has a garden of more than 24,000 roses. Czech children asked German children to help plant them.

“You can’t go there without changing your life,” Ray said. “It’s the same with Trinh’s art.”

Hiền Văn Thạch stands on the shore of Ocean Beach in San Diego.

“We can remind others of healing,” she said. ” … This work reminds me healing is possible and does happen.”

She has struggled at times to keep faith in the idea of healing in the face of pain. She remembered the year when her best friend died. The first artwork in the book is a tribute to her. A woman sits on the broad back of a water buffalo. She is looking upward, her face stricken, her knees drawn under her, and her hands in her lap, cradling a dead bird. In the light above her, a living bird spirals upward.

Mai’s friend Kelly was 29 when she was diagnosed with breast cancer. Kelly was 5 foot 9, with the coloring and stature of Finnish forebears and a deep enthusiasm. She would drive three and a half hours from Seattle to bathe in her favorite stream, Mai said. Kelly’s breast cancer became bone cancer, and Mai created physical manifestations of her prayers for healing. She and Hien often hike together along the Pacific coast, and on these long walks she began to gather driftwood and carve it into a physical mending of bone. She shaped weathered wood like a tibia, a fibula, and bound fractures with string and a Viet Namese newspaper she found in the grass. She shaped a series of sculptures, all from found material, and built wooden boxes to hold them.

After Kelly died, Mai found a stone at the foot of Kelly’s work table. It was split, and Kelly had paintedArapaho on the surface: “You are.” She was going to add “enough,” Mai said, but the stone has only the first two words, an uncapped affirmation.

Losing a friend to illness is one kind of pain, and indifference or deliberate violence is another.

“Sometimes my forgiving others has come from a place of not being able to carry that burden of being angry,” she said. “I know how much I love my family — and those who have hurt me. … It becomes an offering of peace, whether or not they know it.”

In the face of the vicious things people do to each other, Ray said, unison — God, love, courage — can give people a way to keep going, to live the fullest lives they can, to be the people they want to be.

He has heard this language in an annual ceremony when the Nez Perce in Montana invite descendants of the U.S. cavalry from the battle of Big Hole to share a time of remembering with them. The Nez Perce were trying to cross into Canada in 1877 when the cavalry attached their camp in the Bitterroot Valley. Today they carry lanterns into the darkness and sit together in peace and recognition.

People of the Cheyenne and the Arapaho also lead an annual healing run every year in November, 173 miles across Colorado from Sand Creek to Denver, to honor the people who endured the Sand Creek Massacre and the people who died there, when when Colorado Volunteer Cavalry troops attacked peaceful people in December 1864.

Ray admires the courage in these ceremonies.

“We have to go through fracture,” he said. “It is a part of life, like seasons. Unification exists and gracefully arrives, imminent.”

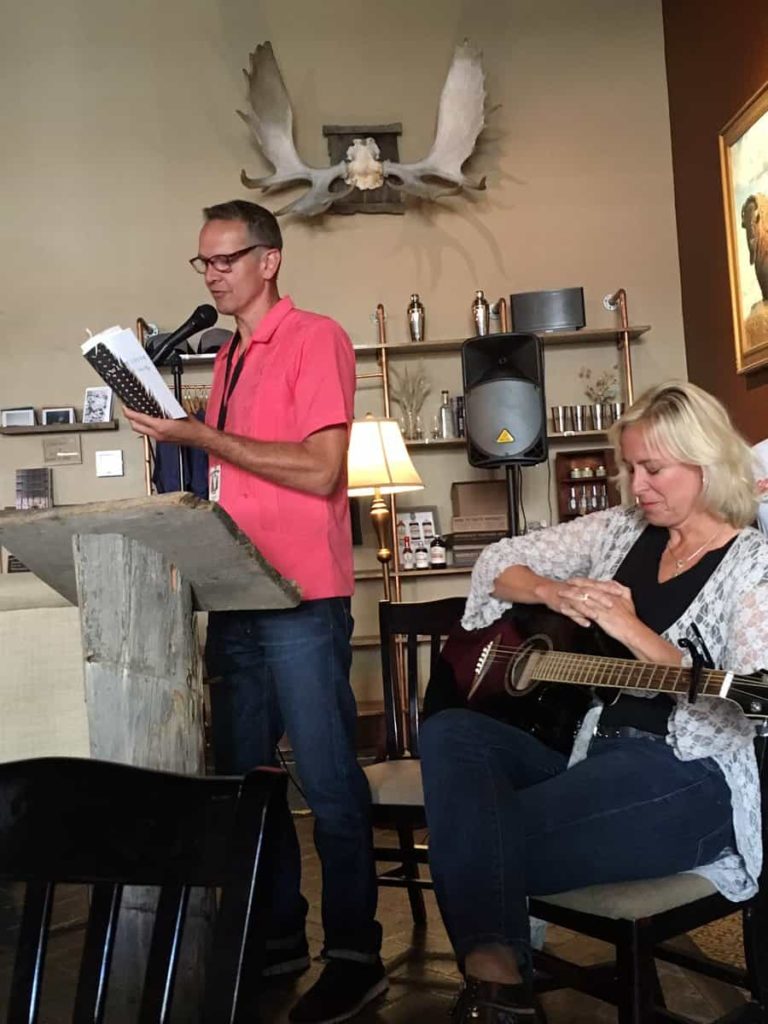

Shann Ray and his wife, Jenn, play music together in Missoula, Montana.

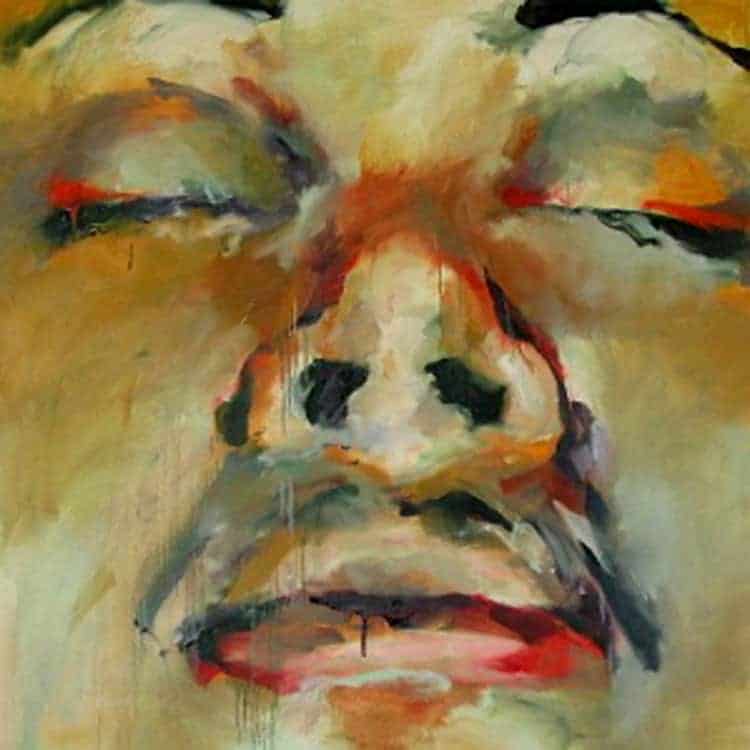

He thinks of Mai’s artwork on the book’s cover. She created its abstract earth-tones from the autumn amber shading of her grandmother’s aging skin, and superimposed in a white outline, a dove spreads her wings. When he first saw it, he said it looked like an atomic bloom. The blast would vaporize everything, turning a bird into an instantaneous ghost.

And yet for him, in Mai’s hands the image holds peace and transcendence and love for both of their grandmothers.

Both women had a deep influence on them.

“(My grandmother) was the spiritual anchor in our family,” Mai said. “She was a fervent Catholic and one of the most progressive people … She was one of 12 children, and she had 10 children and 13 grandchildren. And she was such an independent thinker. She held on to tradition and she lived it … and she was such an inspiration in my life.”

“Everything Trinh has just said I could say about my Czech grandmother,” Ray said, “except that she was an agnostic who hoped for God. … I think of her in trying to honor my view of faith.”

Throughout his work, he acknowledges the destructive depth of fission and turns again to wonder. In a world of subatomic particles, people can be as solid as granite and as insubstantial as electrons.

“We’re physical, and we’re already transparent,” he said. “We’re already made of light. I don’t know that that will be different after we’re dead. It’s a leap of faith. Among equal leaps of faith, I like the one about light.”

Light returns in his work, Mai said, even in the depths, like deep-sea bioluminescent creatures that have light within themselves.

“Scientists believe we have light in our eyes,” she said.

“Depending on our reception of light,” he answered. “If we decide not to receive, we will not take it in.”

He sees too often in the West an avoidance of responsibility, he said: “Militarism, racism, poverty have gotten us to a place where we think instant gratification is God. Any time you see someone take responsibility and live gracefully and not blame the other, the light increases. My wife talks about it a lot. She’ll say, look at those eyes — those are dead eyes. Victor Hugo believed every dry eye is a dead soul.”

His wife’s voice repeats in his poems, looking at the stars, talking in the dark, witnessing a bear on the mountain, calling him into a living relationship with the world.

Mai and her husband too have held each other through fracture.

“Hien and I spent the first seven and a half years of our marriage apart,” she said. And she was very angry then. She saw no reason in it. It was completely unjust. It was a fracture they did not cause, that others caused. In those hard years they needed to be fully attentive, she said, and now their relationship is solid because of it.

“I can say it is worth it,” she said, “because I know the man he is, and I honor the man he is. He is so faithful. If you asked him, he would think it was worth it too. It’s amazing.”

This is a time of crisis for many families facing fractures, she said. She and Hien are helping immigrant families who are facing deportation and exile and fighting to stay here where they are at home. He comes from a loving family who came here from Viet Nam with education and few resources, and he grew up in a hard neighborhood in Southern California. He worked his way through college, playing football on an athletic scholarship.

“I see his father in him all the time,” she said. “We are going through so much now. We need to rest. I want to make sure he’s all right. He sometimes takes two trips in four days, and it’s always urgent. When they need something, they need it. He’s getting out of the shower at night and leaving to be at an 8 a.m. meeting in the morning. I’m concerned about his health. He picks up his duffle bag and says ‘babe, I’m doing this with love in my heart.’”

In Hien she recognizes the deep quiet moments Ray and his wife share in his poems. They are sonnets in form if not in rhyme, and when the fission feels too great for the physical world to sustain, he will return to her, talking at the kitchen table, or walking together, sharing the copper butterflies in the bunch grass, wolverines above the tree line and the sound of meltwater in the canyons.

“… we only live only breathe

each day her unbraided hair down over me

the lace at the window

embroidering us silver

in the dark still sleeping before dawn.”

Trinh Mai Thạch and her husband, Hiền Văn Thạch, hike near the coast in Southern California.