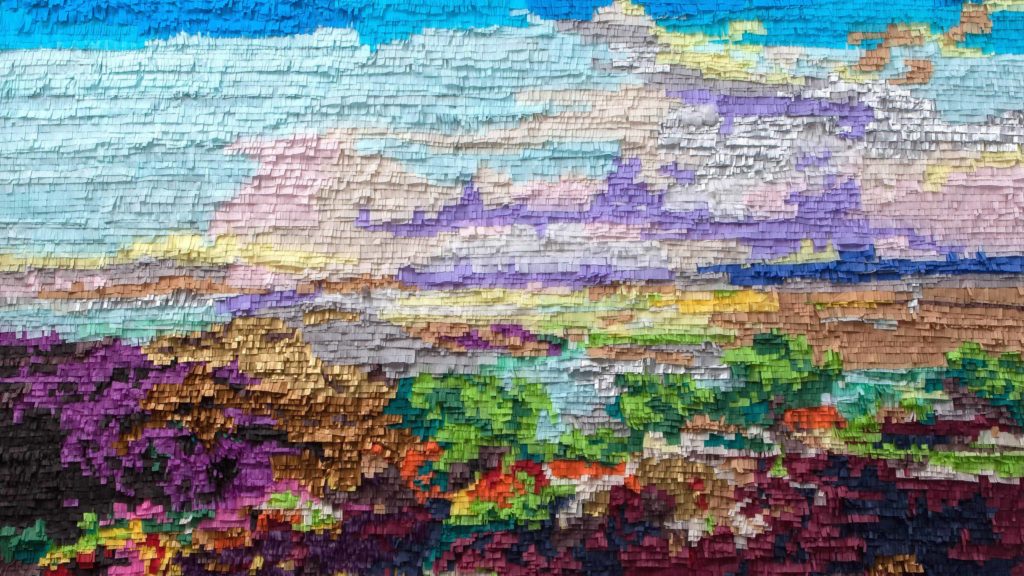

In a studio in the Nevada desert, Justin Favela is transforming the paintings of Jose Maria Velasco. Velasco was a Mexican artist more a hundred years ago. He became internationally famous for his landscape paintings, says Mass MoCA curator Alexandra Foradas.

Favela works with the paper strips used to make piñatas, she says, and in his hands a landscape can change dramatically. A mountain slope of reddish sandstone and scrub becomes bright and playful.

For many people, Velasco’s work came to be symbolic of all of Mexico, she says, and in Favela’s abstracted take on it she sees him pushing back at the identity Velasco was painting in romantic hills where the people are gone.

Mass MoCA is reaching across boundaries this season.

Puerto Rican artist Gamaliel Rodríguez has opened a wide landscape of mills and mountains, half real and half dreamlike in ink and a glint of gold, and Argentine artist Ad Minoliti has filled a gallery with bright abstract paintings.

And this summer, as the museum re-opens on July 12 after four months of shut-down in the Covid-19 pandemic, it brings hew work in the galleries, including Kissing through a Curtain, a new group show of some 10 artists including Favela, exploring the idea of translation.

It is an idea that has surfaced over and over in studio visits over the last several years, said the show’s curator, Alexandra Foradas, in a conversation on the show before it took shape in the galleries. She often travels to visit artists at home and see their work, she said, and over and over again, ideas of translation and communication have kept coming up.

Artists talk with her about breakdowns of communication, she said. She sees a translator as someone straddling a border. They stand at a boundary, trying to reach someone on the other side. Their ideas may not always get across — but it is vital to try.

She likes to base group shows organically on ideas that artists bring up with her, and as she began to follow this pulse, this show took shape.

Its name comes from an essay by the writer and editor, actor and poet Kwame Dawes, born in Ghana and now a professor of English at the University of Nebraska-Lincoln. In a conversation with poets and translators, Foradas said, he remembers a woman who often translates between Belarusian and English. She says in Russian poetry, meter and rhyme are contemporary, but translated into English they can sound stilted and old-fashioned, and English poetry translated into Russian can feel like prose.

“She asks the group how you would feel if you were always kissing through a curtain,” Foradas said, “and someone answers, better than not kissing at all.

“Translation is a generous attempt to connect, and it is important even if it fails.”

It is always a creative process, she said — think about translating a poem. A poem speaks not only in the words on the page, but in suggestions. Some elements a reader understands simply from living in the same world. Some of the poem’s meaning comes from context and association and allusion, she said. A translator has to find the right words to call up associations — it’s not only knowing language, but culture. And it’s sound and rhythm and momentum.

“The music of the language can be so much of the meaning.”

Nasser Alzayani will shape his work here around a poem. He is a Bahraini-American artist working on his MFA at the Rhode Island School of Design, and he is re-imagining an earlier work in this show, Foradas said. He will bring a series of tablets made out of sand. The tablets bear a poem in Arabic, a song about the Adhari spring.

It was a natural pool, well known for hundreds of years, and within the last 10 years it has dried up. Alzayani will include sound, she said, an oral history from interviews, as many different people share memories of a place that has gone, gathering history like grains of sand before they slip through their fingers.

Alzayani has researched the spring and its vanishing. The spring dried up, Foradas said, because the water was used to irrigate distant farms at the expense of local people and wildlife.

He has a series of works on it named for a phrase she finds beautiful, watering the distant, deserting the near, used to describe someone who abandons their responsibilities and leaves their family in need.

He will write the poem on the surface of the sand in raised letters made of sand. He uses a laser-cut stencil like a screen print, Foradas said, sifting and packing the sand to create the script.

Even when the work is new the lines will be only partly readable, she said, and over time they will wear away. They are held together loosely, like a sand castle, and as people walk nearby the vibrations of the floor will slowly loosen the grains, and the tablets will fall apart.

Something can be lost in translation, Foradas says, recalling Salman Rushdie in an essay in Imaginary Homelands. But he writes, and she agrees — “I cling obstinately to the notion that something can be gained.”

Rushdie points out that translation means to carry across, she said. An idea or a story or a person moves through a border. People who migrate are in translation. And she is interested in the ideas translated and what happens to them in motion.

Artist Aslı Çavuşoğlu has an eye for the ways people talk between the lines.

She lives and works in Istanbul and on an island outside the city, and she will bring a mix of new commissions and recent work to Mass MoCA, Foradas said. In a broad exhibit, Just the Push of a Voice, she will gather new commissions including Annex, an installation based on graffiti she has seen over the last 10 years in Istanbul.

Street artists will write revolutionary messages on the walls, Foradas said, and within a day people of opposing views will render the letters into abstract forms. Çavuşoğlu has been creating a new alphabet from these abstractions, with Turkish and English alphabet.

Annex follows an earlier work, A Few Hours after the Revolution, lighting up graffiti that originally included Devrim, the Turkish word for revolution.

People can sometimes tell a great deal in symbols or in a few words, sometimes without knowing it. In Not Equal To Çavuşoğlu sets out 19 pairs of words drawn in cuttlefish ink on restored paper. They seem to mean the same thing — and they can mean widely different things. In Turkish, Foradas said, the way you say something as seemingly simple as good morning can show your political affiliation or your faith.

Here Çavuşoğlu will build pairs of words in English that work the same way, with similar meanings that can suggest very varied points of view, like Merry Christmas and Happy Holidays … or undocumented and illegal.

“The way we speak is so often coded,” Foradas said, “and filled with information about our beliefs in ways not always talked about openly.”

Çavuşoğlu also considers words people try to erase. She has created a song from 191 words the Turkish government once banned from the airwaves.

In January 1985, Çavuşoğlu explains in her website, the General Directorate of the Turkish Radio and Television Corporation (TRT) banned 205 words on television and radio broadcasts — words like “memory, remember, recollection, experimental, motion, revolution, nature, dream, theory, possibility, history, freedom, example, conversation, whole, life.”

The meeting of music and art intrigues Foradas and several artists in this show, including Osman Kahn, an artist who directs the MFA program in the School of Art and Design at the University of Michigan.

He is working on a new commission for Mass MoCA, an installation with sound. popular music in the U.S. usually follows from Western, European beginnings, Foradas said — the octave, the 13-note scale, in 3-4 or 4-4 time.

“He is interested in what would happen if dance music was written from an Indian tradition,” she said.

For Mass MoCA, he imagines a kind of three-dimensional stage set inspired by Mughal miniature paintings, especially of thrones — an emperor sitting on a carved chair under a canopy.

He draws his sounds from Indian classical music, she said, from the complex melodies and structures and improvisations of Ragas. A Raga is a language of sound. Indian classical music has many, many ragas. In each one the tone and length and order of the notes holds a feeling, a stage of mind. And so some are meant to be played at a time of day or a time of year — imagine a music meant to be played at sunrise in the first days spring.

Khan is creating new music influenced by an algorithm he is creating and an an electronic tabla, a drum played with the hands and fingers in a rhythm that can rise and fall like a speaking voice.

Jimena Sarno, an artist in Argentina and the U.S., is also creating new music in her work. This spring she will release a vinyl record of taracatá trabaja, a sound installation she composed and designed with Argentinian musician Axel Krygier.

The music is based on an Argentinian folk song, Malambo del Hornerito, warmly honoring the hornero, the national bird of Argentina.

Horneros are small birds, red-brown and white, “monogamous and hard working,” Sarno says as she describes the work on her website. They are also called red ovenbirds, because they build nests out of mud and straw: a red-brown dome a foot tall with a rounded door in the front.

The folk song plays with two onomatopoeias, she writes: “taracatá, the sound of hard work (fields being plowed and nails being hammered) and chapalea, a from the sound of squelching in mud,” giving a sense of “… making a home, pleasure, well-being and dignity.”

At Mass MoCA, four singers will perform the score for four voices at the opening — Gemma Castro, Vera Lugo, Molly Pease, and Rosalie Rodriguez. And the music accompanies sculpture, as she glazes the notes and the birds on hand-thrown ceramic plates.

Brazilian artist Clarissa Tossin has called on music and dance to translate a house across 4,000 miles, along the Pacific coast to the cities where its design has its roots. She will bring Ch’u Mayaa to Mass MoCA, a film linked to an installation at the Whitney Museum of American Art in New York in 2018.

She describes it as honoring and reviving “the overlooked influence of Mayan architecture on Frank Lloyd Wright’s Hollyhock House.”

Hollyhock House is now a UNESCO World Heritage in Los Angeles. It has sunlit dun walls like blocks of stone set at a steep slant. Patterns of linked squares repeat on the moldings and in the windows. Rectangular lights shine through slats of wood, and stone steps lead into a courtyard garden lined with square pillars.

Tossin imagines the house as a temple. In her work, a woman dances there with gestures and postures found in ancient Mayan pottery and murals. She reunites the house with the Mesoamerican tradition and architecture it belongs to, linking it through centuries. The title means “Maya Blue,” Tossin explains, an azure pigment in Mayan pottery and murals, known for lasting through weather and time.

This story first ran in the Hill Country Observer in February / March 2020, as the show was due to open on March 21 until Covid-19 caused the museum to close for the spring. My thanks to editor Fred Daley.