On a short winter day, Edith Wharton is writing a novel. She has recently come to this light stone or stucco house in a row of houses, on a tree-lined street a few miles north of Paris. The French windows lead into the gardens, the way her living room in Lenox once opened onto the terrace.

World War I ended a little more than a year ago. In almost every family around her, people have died.

A hundred years ago, in the first months after that cataclysmic violence, she began writing The Age of Innocence. She published it in 1920, and year later she would win the Pulitzer Prize, the first woman ever to receive it in fiction.

This winter, as readers and writers celebrate the book’s centennial around the world, her own copy of the book has returned to her library at the Mount.

People are paying new attention to a novel where a woman can live independently in a street of budding trees and a stir of ideas, good conversation and tangible companionship.

And a man can say bluntly: “Women ought to be free — as free as we are.”

The reality of the book moves Susan Wissler, the Mount’s executive director, and Rebecka McDougall, the Mount’s director of communications. It shakes them, knowing that Wharton held it and read it and wrote about it.

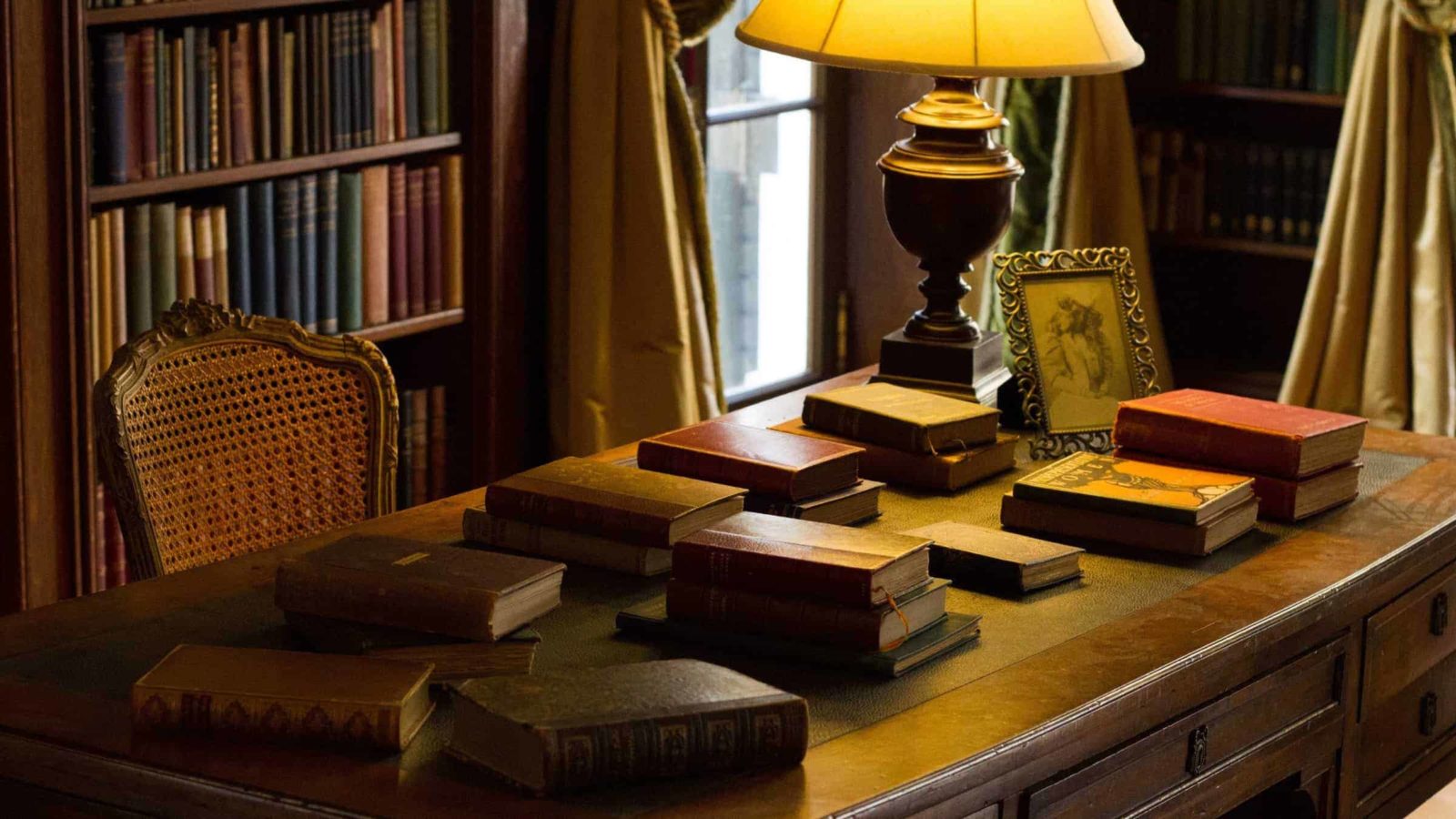

“It is intensely meaningful for us,” McDougall said, standing by Wharton’s desk and a tall bookcase. And it is inspiring new investigations as The Mount plans centennial celebrations, looking closely into how Wharton wrote Age of Innocence and how people read it then and now.

She sees a broad and growing excitement in Wharton and the Mount. Scholars are coming to the Wharton’s library from across the world, from the Oxford University Press to New Zealand and Kyoto, said the Mount’s librarian, Nynke Dorhout.

“I’m amazed at how many contemporary writers cite Age of Innocence as one of their favorite books,” McDougall said.

Public programs director Michelle Daly had just returned from listening to nationally awardwinning novelists talk about The Age of Innocence at Symphony Space in New York City: Elif Batuman, who will come to the Mount this summer, and Colm Toíbín, Fiona Davis and Min Jin Lee.

Wharton was nearly 60 when she wrote her 12th novel, looking back to New York in her girlhood in the 1870s. Newland Archer, a young man from a wealthy family in New York, is on the edge of getting engaged to May Welland, when her cousin, Ellen Olenska, comes back to the city. Ellen had married a Polish nobleman who treated her brutally.

She has left him and come to live in a house on West 23rd Street with wisteria over the balcony and books scattered about the living room, in a neighborhood of writers, journalists and musicians.

Wharton describes her as “full of conscious power.”

“She was taking on gender in a way we’re only now considering,” Daly said.

Ellen is fearless and familiar. She is open to art and music, dance and poetry. She has an intelligence, passion, creativity and directness that her New York relations shy away from.

Newland finds himself drawn to her, and she moves him to impulses of honesty and passion that put him in conflict with the rich, conservative society he comes from.

The volume in the Mount’s library is the sixth printing of the first edition. This is the edition Wharton kept for herself, the Mount’s house manager, Anne Schuyler explained.

Wharton revised the first printings, and this one may have felt most complete to her.

Dennis and Andrea Kahn have given it to the Mount to celebrate the 100th anniversary, and Dorhout marvels at Wharton’s signature and bookplate as she traces it this copy back through Wharton’s godson, Colin Clark.

In its light, Wissler has been studying Wharton’s revisions, and some she finds deeply revealing. In the earliest printings, she said, Newland and May’s wedding opens with a line from a burial ceremony, “For as much as it hath pleased almighty God of his great mercy …” It comes from book of common prayer, a book Wharton had known intimately since her childhood.

Re-reading the book, Wissler finds the sensation of being buried in many places. An editor asked Wharton about that opening line in a letter, she said. Wharton spent a sleepless night over it, and she changed to the more familiar opening for the wedding ceremony, “dearly beloved, we are gathered here …”

The first choice feels like a powerful subconscious reaction, Wissler said, as though in that moment, when Newland turns away from Ellen, Wharton sees the death of the intense, ardent, active life he could have had.

Wharton herself left New York, left her husband and family, and left America. She became a writer and came to Paris, as Ellen does. By the time she wrote Age of Innocence, she had gotten a divorce, had a lover and insisted on more. She had chosen a creative life and friends. And she had lived through five years of World War I.

“In the war, everything changed,” Schuyler said. “The rules of society changed. They lost an entire generation in France and Britain.”

Wharton had lived in Paris under German bombardment. She had stood the trenches within sight of the German guns. As she began Age of Innocence, men were coming home from the war shell-shocked, Daly said — or not coming back.

She thought of different plots, Wissler said. But she never imagined a plot where Newland breaks off his engagement with May to marry Ellen Olenska. And she never thought out one where he touches what he sees in May’s soul, the “glow of feeling that it would be a joy to waken.”

In Wharton’s book at the Mount, someone has set off a passage near the end with faint pencilled lines. It describes all that Ellen Olenska has lived and Newland has not: “She had become the composite vision of all that he had missed.”

She is living in a sunlit street near the Louvre, among paintings and gardens and conversation. And he turns away.

But Ellen keeps her independence, Daly said, and she is happy in it. And that is radical.

This story first ran in the Berkshire Eagle. My thanks to features editor Lindsey Hollenbaugh.