Allison Maria Rodriguez was floating in salt water that can have ice floes at this time of year, but she was there in the six weeks of summer, in the brief thaw. She was drifting in a kayak, almost on a level with the surface of the water, in a pod of beluga whales.

They swam around her, she says, as close as a few feet away, social and alert, surrounding her and looking at her with their rounded foreheads and dark eyes and smooth, muscled bodies 18 feet long.

Rodriguez is a multimedia artist, and she has stood at the edge of the Arctic in Northern Canada to create the scenes, vast and small, in all that moves, on view this month at Installation Space. Until November 28, you can open an unassuming door on Eagle Street in North Adams and walk into Manitoba.

She often travels for her work, she told me by phone. Her films and photographs grow from a desire and urgency to see places new to her. In this show, she has had the chance to come to a place she finds viscerally beautiful. And it’s disappearing.

She came to Manitoba on an Earthwatch Communications Fellowship, and she stayed with scientists at the Churchill Northern Studies Centre who are studying climate change and life in the Western Hudson Bay.

It is remote enough that she had to fly in to an airfield about the size of the one in North Adams, on one of their few flights a day. Their only train service was flooded in the thaw. Churchill has a small community, she says, and a research station where scientists come from all across the world to study climate change. And they always study in pairs — because of polar bears. One always keeps a watch while the other collects or observes what they need.

The northern lights dance above the open ridges and the debris of space flight near Churchill in Manitoba, in a film still from Allison Maria Rodriguez' art installation 'all that moves.'

She met scientists studying bears, birds, invertebrates, and an amalgam of ecosystems. In the North, along the coast of Nunavut, the sea has a polar climate — Hudson Bay, Tasiujarjuaq in Inuktitut, Wînipekw (Winnipeg) in Eastern Cree.

Tundra stretches out in scrub and mosses, and taiga shield covers ridges of bedrock in trees growing at odd angles in soil that thaws and freezes — dwarf birch, spruce and pine and juniper around the lakes, and plants adapted to the cold — rock harlequin, fire snag, fragrant Shield fern and saxifrage …

Rodriguez could only leave the research station with a guard and guide, because of the bears. In the first half of her stay, she went out with biologists Sarah-Béatrice Bernier and Marie Helene St. Gelais, studying daphnia — tiny crustaceans with filaments of antennae. They are in the same extended family as shrimp, but almost microscopic, just on the edge of what human eyes can see.

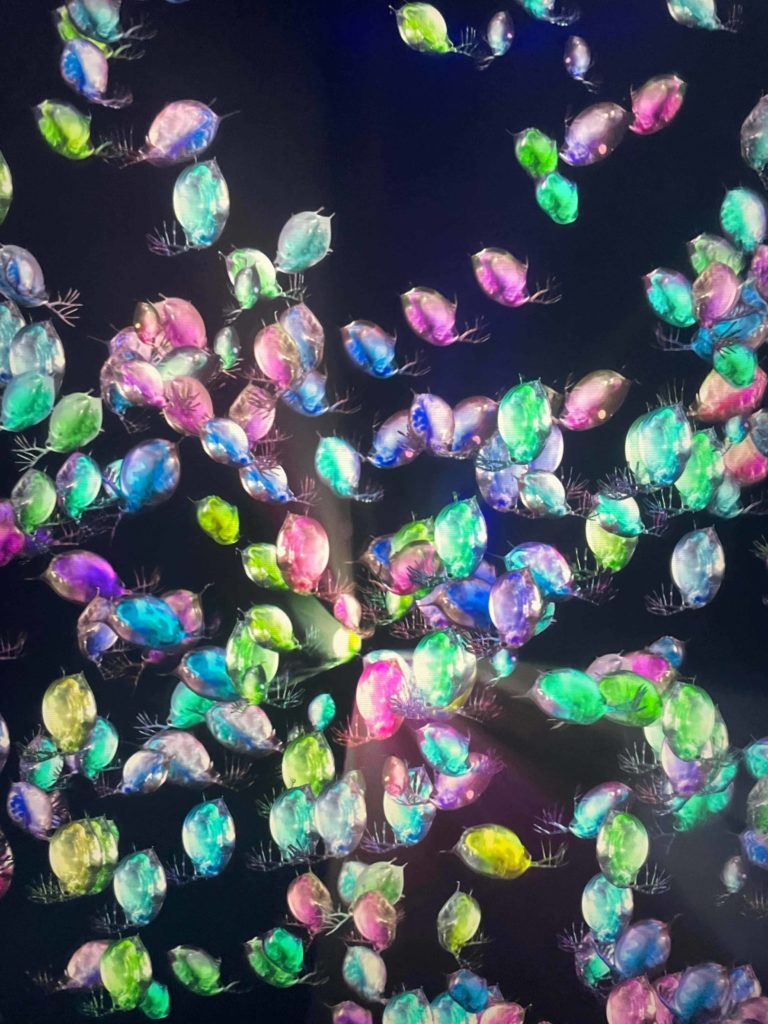

Daphnia, tiny crustaceans, swim on screen in Allison Maria Rodriguez' art installation 'all that moves.'

In her show they appear in prismatic drops of color, gleaming iridescent on this screen. And they are swimming in water rapidly becoming warmer. Bernier and St. Gelais are tracking them to see how the rising temperatures affect them, how much change they can withstand.

Rodriguez would come with them to seasonal meltwater ponds to catch Daphnia with fine nets. They showed Rodriguez a microscopic world, she says. It’s a sobering kind of marvel, to think that scientists are studying these minute beings because they are like us. Understanding how they respond to this rapid change in the water they live in can tell us something about what we have in store.

In return, the biologists felt the depth of her experience, being out on the water and learning the land. She saw caribou and arctic foxes, she said. And she found it intriguing to talk with them as an artist among scientists. They are keeping exact notes, taking measurements, following changes in patterns over time. And they felt a value in having here there, whether or not she created artwork later on — her perspective and her ways of seeing renewed their awareness of connection to the place and its beauty.

She was not the only one looking for that connection or the only one new to the landscape. In the second half of her stay, she worked with an Earthwatch team of teachers. In that stretch, she says, she was out in the mud herself, looking for insects, larvae, life in the lakes in the short weeks when they thaw enough for life to burgeon in the water.

A crashed plane overlooks a lake and valley near Churchill in Manitoba, in a film still from Allison Maria Rodriguez' art installation 'all that moves.'

Six weeks of summer means a short stretch of thaw. Ponds appear out of the ice. Insects lay eggs and develop — and bite. The team had to cover every inch of skin, and she would walk out into the mud wearing a jumpsuit, netting and waders. It’s not the way she is used to experiencing a place in her body, Rodriguez says.

She couldn’t film these experiences, she says, but she felt them — they connected her to a part herself that had been there but not awake. And the films she has made here are different from her earlier work. She has usually created natural scenes in a kind of digital collage, planning and merging them through technology.

Here in the north she would come to a place where she felt a visceral energy, turn on her camera and let it go. In the open spaces, she would record stillness. In the quiet space in North Adams, the only sound is mixed from recordings of the wind.

A connifer glimmers in dim blue light in Allison Maria Rodriguez' art installation 'all that moves.'

She felt a history and acenstry here, she says, past and present. Manitoba is the homeland of the Sayisi Dene, the easternmost of the Dene people. They have lived here for centuries and followed the caribou. In the 1950s, the Canadian government forcibly relocated a community of the Sayisi Dene to Churchill, away from the herds, and the faced genocide — for 20 years, two generations, they lived in tents and shanties, and then government housing that in no way fit people who lived on and with the land. More than a third of them died. In the 1970s, the families who survived began to return to the lake shore, to the north.

On a ridge near the Churchill Center, Rodriguez came across a plane that crashed long ago. It is sitting on a fall of stone as bare as the quartzite along Pine Cobble below the Appalachian Trail. The cockpit is open to the sky, and through a hole in the fuselage light is reflecting on a lake far below. As Rodriguez has framed the shot, she seems to be standing behind the pilot’s seat, looking out across the valley, and a small plane is coming in to land, looking barely large enough to carry a co-pilot.

And here the Northern Lights shimmer over the remains of rockets that once studied them. Churchill was once a range for launches, and the remnants stand stark under the vivid green sky. People left them, Rodriguez says, because it was easier than picking them up. She wants to show the objects jettisoned and never dealt with. And she wants to show the relationship between all that is disappearing in the north and all that is disappearing here.

People forget about places they have never experienced, she says. The teachers she met here have come because want to feel bonded, part of a natural whole, so they can bring that hands-on understanding into the classroom and teach climate change in an organic way. If they know how it feels, then they can help the kids they teach to feel it too. Science, hard facts, are not necessarily enough to get the message through to us, Rodriguez says — because we’re seeing them, and climate change is still accelerating.

At the center of the room, a pool of water melted from local ice glows in the low light. She has projected onto it an image of the water in Hudson Bay. The water is warming there too. In 20 years, she says, Hudson Bay will have no ice on the water at all in the summer. The polar bears will have nowhere to stand.

The same water runs through here, she says, and as she describes it, it feels very close to home. We live over the ridge from the Hudson Valley and the river — the river the Mohican people call the Mahicannituk. they named the Hoosic, the river that runs through North Adams. And the Mahicannituk gave them their name, the people of the tidal river, the water that is always in motion, rising and falling.