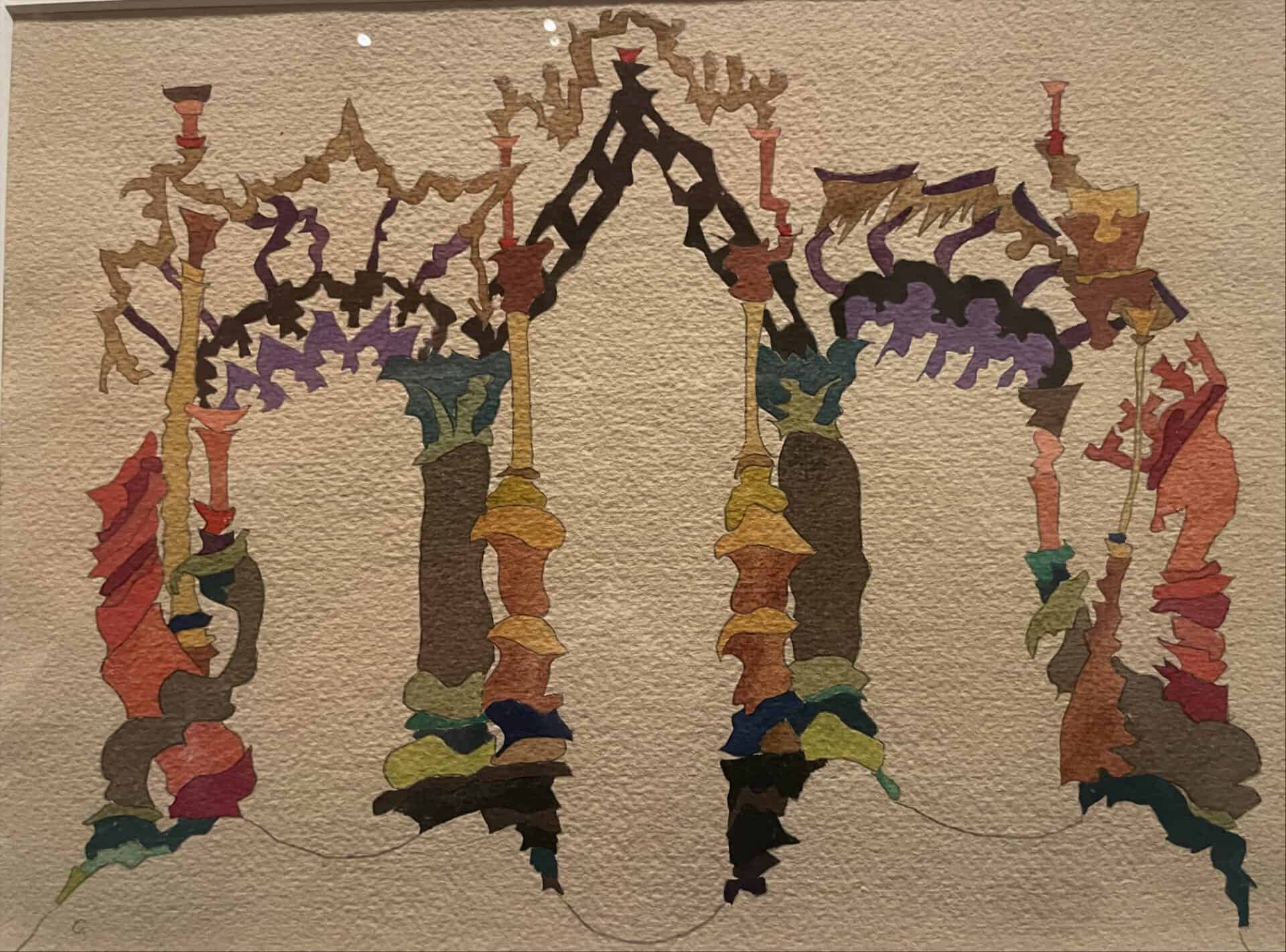

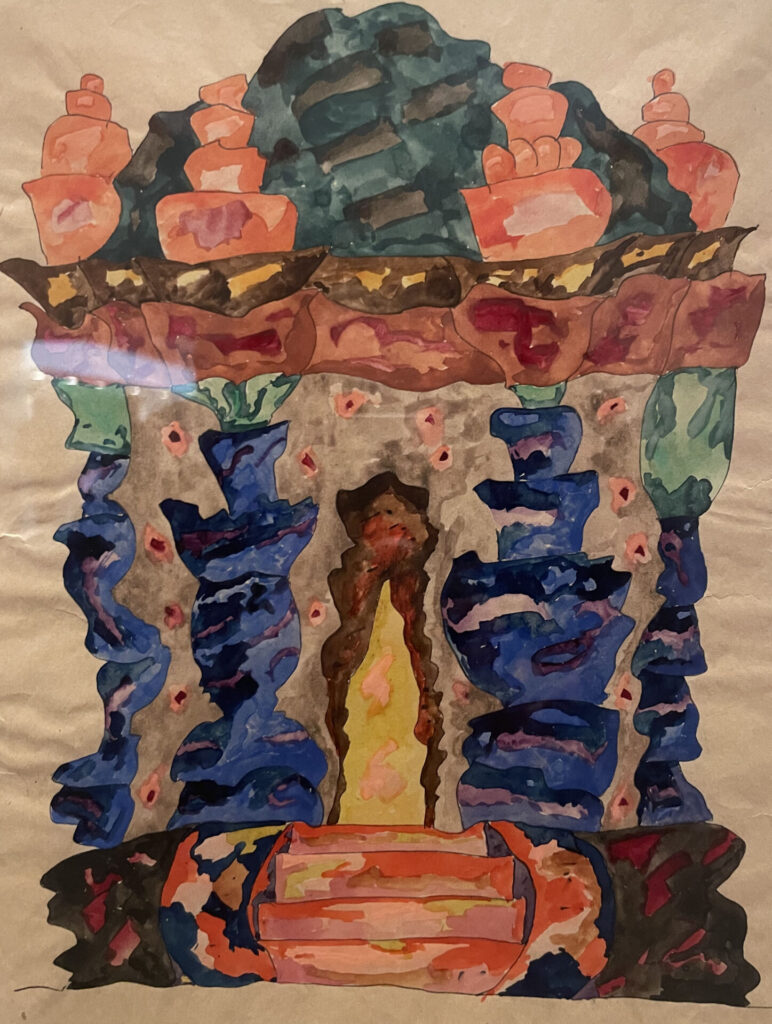

In Germany between the wars, Paul Goesch drew doorways that looked like they were growing. If you could walk through this arch into a house or a temple, it would be a living place — like the rooms in Octavia Butler’s Dawn and Adulthood Rites, where sentient beings seem to have a symbiotic relationship with their shelters.

His columns leaf out like trees, arches bloom into trellises and pilasters pop up like mushrooms, russulas and chantarelles.

I’m wandering through Portals, the Clark’s new spring exhibit — the first show dedicated to his work in North America — and revelling in the kind of art and conversation on the walls that sends my thoughts gleefully in all directions.

In these difficult years when he was emerging, for a brief moment, a group of artists and architects looked to nature and organic forms.

Robert Wiesenberger, curator of contemporary projects, sets Goesch in the context of his fellow artists. And so I am powerfully struck by Hermann Finsterlin’s studies for a building that curves like weathered sandstone.

Paul Goesch imagines architectural structures in color and curving organic forms in Portals at the Clark Art Institute. Photo by Kate Abbott, courtesy of the Clark.

Paul Goesch’s vivid and varied architectural drawings envision fantastic shapes.

Finsterlin was Goesch’s contemporary, as a painter, poet, architect and toymaker — and “he considered buildings to be natural living organisms,” Wiesenberger writes. His studies “might resemble slugs, mushrooms or geological formations … or the chambers of seashells.”

I walk through and wonder what would have happened then if we could have held on to these rich veins of intuition and beauty? What can we do now if we turn the tide toward them again?

Wiesenberger sees Goesch as an an artist and architect experimenting with kaleidoscopic color and inventive playfulness, to “envision new worlds even as he re-enchants the existing one … “

‘He considered buildings to be natural living organisms … (They) might resemble slugs, mushrooms or geological formations … or the chambers of seashells.’ — Robert Wiesenberger, curator of contemporary projects

In the 1920s, he says, Goesch was part of a group of architects around the country who wrote to each other under pseudonyms and sent writings and drawings by mail, like an early analog of social media. They called themselves the Glass Clain, because they often designed in glass; they imagined glimmering towers and houses for working people, and they wanted a break from the country’s elitist past.

But they were short-lived, Wiesenberger says. And Goesch has until recently been erased from history.

As he asks why, he tells us that Goesch lived with schizophrenia for decades. And as I think of the shape of Goesch’s mind and the varying weights he may have carried, I wonder whether the challenges Goesch faced in finding support for his work may have as much to do with the movement of thought in his country, in his lifetime, and his passion for swimming against the current.

Germany was grappling with the trauma of World War I and the loss of a generation. shortages and hyperinflation. Until now, almost all I knew of the art of this period was industrial — Bauhaus — flat planes, blank cement walls, plastic and steel — the kind of minimalist man-in-the-machine thinking that often deliberately denies any connection between humanity and nature, and leads into brutalism in the 1950s.

Paul Goesch imagines architectural structures in color and curving organic forms in Portals at the Clark Art Institute. Photo by Kate Abbott, courtesy of the Clark.

And here are Goesch’s arches standing in contrast — a pagoda roofline with an apogee like a caterpillar held up by acorns and strawberries. His forms are irregular, twining, vivid. And almost none of them follow straight lines.

He had company in the 1920s. Examples come to me as I follow the lines of his archways. German engineer Walther Bauersfeld designed the first geodesic dome, and Buckminster Fuller was spreading the idea here in the U.S. In Barcelona, Gaudi was designing the melting forms of Sagrada Familia.

And, as I know from the Clark’s 2019 summer show, in Norway, artist and naturalist Nikolai Astrup was watering a living turf roof at his home and studio on the Western coast.

‘The conditions that enabled Paul Goesch’s moment in the sun lasted only briefly.’ — Robert Wiesenberger

But the tide shifted. In Germany, “the conditions that enabled Paul Goesch’s moment in the sun lasted only briefly,” Wiesenberger says in the closing panel in the show.

By 1923, under Soviet influence, the Bauhaus movement had turned into a “sober and scientific functionalism” — flat, square, manufactured and colorless. Glass as a medium, which had once had the intricate possibilities of frost flowers, crystaline structures, waterfalls … retreated into negative space.

Then the Nazis steamrollered even those ideas. “Following its rise in 1933, the Third Reich either crushed or co-opted varios strains of the avant garde,” Wiesenberger says, “with dire consequences for artists and architects.” And Paul Goesch died in a Nazi prison. “Nazi doctors … would murder some 300,000 patients with mental illness.”

Paul Goesch imagines architectural structures in color and curving organic forms in Portals at the Clark Art Institute. Photo by Kate Abbott, courtesy of the Clark.

Nora Krug traces a similar movement in this time, away from both innovation and nature; in her new show at the Norman Rockwell Museum, and in her book Belonging, she sees World War II attacking ecosystems, not only in the collateral damage from tanks and trenches, but deliberately — armed forces targeted forests to destroy elements of the way a nation thought and understood itself.

And she traces the distance she felt, growing up in Germany in the 1980s, from connection with the woods, and from poetry and language, that had once woven together into an intuitive German sense of the natural world. I think of her show in conversation with Goesch, and I wonder … What would have happened then if we could have held on to these rich veins of intuition and beauty? What can we do now if we turn the tide toward them again?

Paul Goesch imagines architectural structures in color and curving organic forms in Portals at the Clark Art Institute. Photo by Kate Abbott, courtesy of the Clark.

Wiesenberger opens the show with visions of living spaces unbound from right angles or the weight of steel. When he draws and dreams, Goesch can imagine his forms without limits. “(The Glass Chain artists replaced) the practical, Physics-bound work of artitecture,” Wiesenberger writes, “… with the speculative fantasies of paper architecture.”

What if we take this freedom to invent and turn toward natural structures? People around the world have thought of architecture in passageways and round or domed forms, including here on the land where I’m writing this in my rectangular living room. Portals makes connections to the domed Stupas in Buddhist places of worship and meditation, the domes of Mosques, the ceilings of cathedral chapels and the rings of towers in Hindu temples.

And I’m thinking of Mongolian gers, Mohican wik-wams and Haudenoshaunee long houses, Irish and Scots bothies and stone beehive huts and the passage tombs at New Grange. We have an affinity for rounded spaces, in many places and times.

What architectural forms already mimic nature and always have? People have paid attention to shapes and builders in the world around us for centuries … beaver dams, honeycombs, shapes that shed water, kinds of wood.

What would happen if we brought that understanding back, in places (like much of this country) where we seem to have lost it? In a recent conversation, I learned for the first time about Ben Falk, permaculture farmer who founded Whole Systems Design, bringing together his understanding of the land and his understanding of architecture.

Paul Goesch imagines architectural structures in color and curving organic forms in Portals at the Clark Art Institute. Photo by Kate Abbott, courtesy of the Clark.

What would happen if we thought of architecture in terms of ecosystems? Solar, water, insulation, fluid movement between outside and in … What would happen if we created living spaces with plants at the center of the design — metaphorically as a key element?

As I walk up Stone Hill toward Thomas Schütte’s ‘Crystal,’ I’m comparing his flat planes in muted colors to Goesch’s variety and color. Schütte talks about natural forms too, and he draws the shape of this one-room space from a crystal structure. And he leaves one wall open, so that sititng here on a sunny afternoon gives a long view of blue sky.

But in comparison, Goesch seems more open to the sheer variety and sensory possibilities of nature. His colors and textures almost move on the page. And I wonder why he is drawn to doorways. Knowing the world he lived in, maybe I can understand why he returns so often to openings, membranes, passages … places of change.

Fom the pathway up Stone Hill, the Clark Art Institute shows through the trees, with a view to the mountains.

Events coming up …

Find more art and performance, outdoors and food in the BTW events calendar.