From a distance, the colors shimmer like a crazy quilt of neighborhoods seen from the air, scarlet and blue and yellow, as though the houses were painted as bright as tropical birds, quetzals and hummingbirds and bananaquits. But look closely and shapes emerge. Colors merge under your eyes into one form, like parrot shifting in the light between leaves.

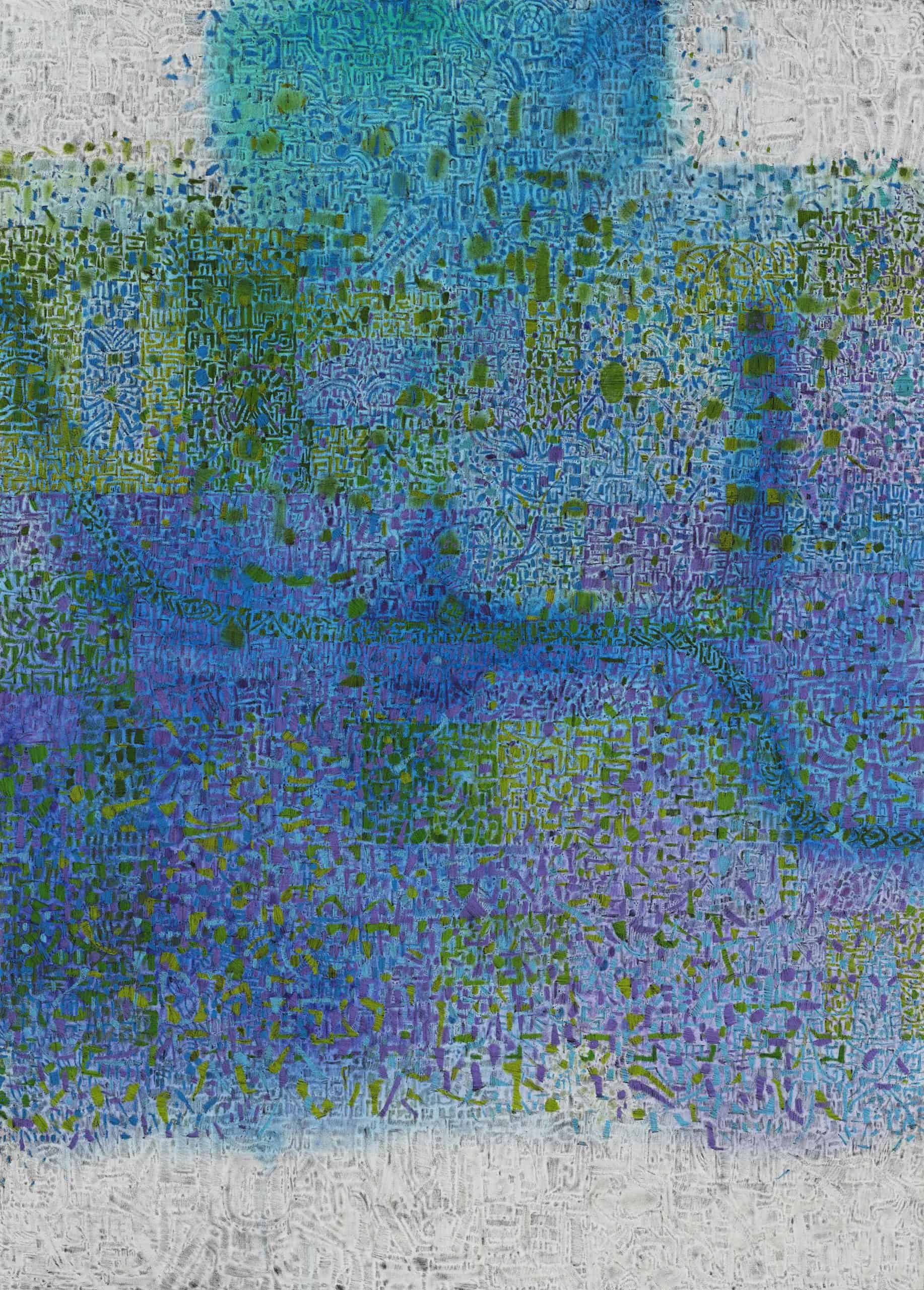

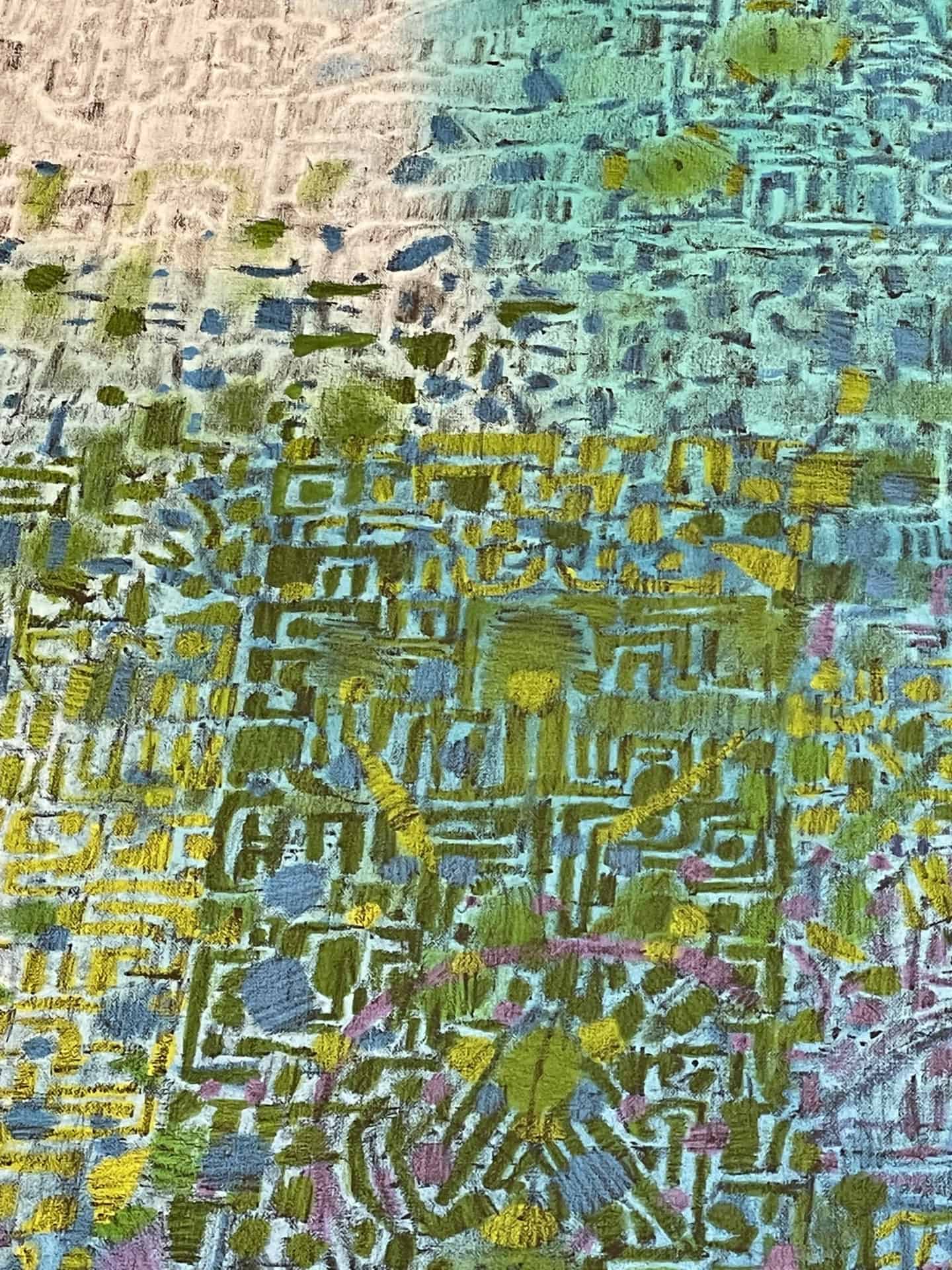

Tomm El-Saieh, a contemporary artist with growing recognition across the country, shows four new abstract paintings in Imaginary City, a solo show of his own work at the Clark Art Institute.

This spring, he has curated a new show of works by Frantz Zéphirin, one of Haiti’s most widely known artists, at the Williams College Museum of Art, with WCMA Mellon Curatorial Fellows Jordan Horton and Destinee Filmore. Zephírin’s work has come to Williamstown just as his paintings are appearing to represent his country in the Venice Biennale.

Wanga Neges appears in bright abstract strokes of paint, seen close up in Tomm El-Saieh's 'Imaginary City' at the Clark Art Institute. Press image courtesy of the museum

They are unique, El-Saieh said, in a long tradition of artwork steeped in the Vodoun faith. Zephírin invokes the spirits of the loa, in textured sunlit landscapes, drawing around them mythical, magical, divine beings. Merfolk float on their backs and open translucent wings in the water. A woman dances in the forest at night, holding a lit candle in a circle of trees. His scenes ripple with textures, in the patterns of light on toe waves and the veined skin of leaves.

Looking at Zephírin’s work now, while it hangs just up the valley from his own, he says he sees shared themes and influence running between them.

“My brother is also a painter, an artist,” he said, “and I see myself and my brother in Frantz’ work.”

El-Saieh keeps close ties to his family and to the Haitian creative world. He lives and works in Miami, where he grew up, and he was born in Port-au-Prince to a Haitian, Palestinian and Israeli family with ties to generations of widely recognized Haitian artists. His brother draws on surrealism, Haitian art and politics, patterns of spiritual connection, he said, while El-Saieh is known for vivid abstractions.

In the name and the work Imaginary City, he nods to the artist Préfète Duffaut, who won international recognition in the 1940s and beyond for his dreamlike landscapes — terraced mountain islands almost floating over the water.

Canape Vert appears in Tomm El-Saieh's 'Imaginary City,' a solo show of large paintings in vivid abstract color, at the Clark Art Institute. Press image courtesy of the museum

Imaginary landscapes have become a popular subject in Haitian paintings, El-Saieh said. They may be influenced by rapidly growing towns and suburbs, villes constructed haphazardly of self-crafted houses.

“It’s an an organic thing,” he said. “It takes over the mountain like a bee colony — it’s intense.”

His own work grows out of a long tradition, or interwoven traditions.

“My focus has a history in Haitian arts,” he said. “I grew up around it. My grandfather opened one of the first galleries in Port-Au-Prince, in the early 1950s, and it still exists. He worked with Haitian masters. The artists had studios in the gallery, and I grew up with the paintings.”

His grandfather, Issa El-Saieh, was a forceful and charismatic man, a traveler with a wide influence. He lived through a chaotic time El-Saieh said. During the regime of François ‘Papa Doc’ Duvalier, when many people were dying, disappearing or forced into exile, these artists chose to stay, and they survived.

Most of El-Saieh’s family had to leave their home and their country, but his grandfather stayed in Port-au-Prince, even through imprisonment.

The novelist Graham Green even based a character on him, El-Saieh said, in a novel called the Comedians, set in the years when Duvalier was in power — Hamit, a well-connected and knowledgeably ironic merchant trader, described in moments of vivd urban color.

“I saw Hamit standing amazed at the door of his shop. The red evening light turned the pools and mud the color of laterite.”

Tomm El-Saieh's painting Vilaj Imajine appears in bright abstract strokes of paint, seen close up in Tomm El-Saieh's 'Imaginary City' at the Clark Art Institute. Press image courtesy of the museum

Issa gathered artists and musicians around him, from across the island and far beyond.

“He had a Haitian big band,” El-Saieh said. “He was hanging out in Harlem in the 1950s

listening to Charlie Parker and Bud Johnson, and he got top musicians to come to Haiti — and they revolutionized Haitian music.”

His grandfather’s band recorded on his own record label, and he became internationally known for a new fusion of American jazz and Haitian rhythms, deeply influenced by Vodoun drumming.

So El-Saieh grew up knowing these artists, and they became strong influences for him. He saw the currents in their work, historical themes, Vodoun spirits — the loa — craft themes.

Tomm El-Saieh's painting Canapé Vert gleams in green and turquoise, seen close up in Tomm El-Saieh's 'Imaginary City' at the Clark Art Institute. Press image courtesy of the museum

He studied with André Normil, a contemporary of Duffaut’s well known for historical and religious themes and daily scenes in vivid color. In his paintings, a family gathers at the dock, on a boat with a forward sail and a flat stern, resting in the sun as a boy tends a fire in a brazier. Farmers in a crowded market square unload vegetables from a cobalt-blue truck. A procession of dancers winds through town on a festival day, wearing bright colors and masks.

El-Saieh’s father put him to work with Normil when El-Saieh was 15. He had been learning on his own, he said, from artwork he liked, and he remembers bringing his work to Normil to look over.

“He said I should stop,” he said, “and look at my work and others.”

Normil suggested that he should understand the patterns that had become common, so he could find original voices — he needed to find his own voice, specific to him.

“I was stumped by that for awhile,” he said. “I came back to it years later.”

He started to take over the family business, the gallery, and then in about 2015 he returned to his own painting and began this new body of work. Haiti does not have a history of abstract art, he said. Zephírin has said to him that abstraction doesn’t exist in Haiti. Haitian paintings can have a sense of vivid color, but they almost always have a central figure, someone or something clear, a person, a chicken, a sailboat.

In his own work and Zephírin’s, he sees the influence of trance, a dreamlike state of mind that Vodoun rituals invoke in rhythm. The sound of drumming is the way they call to the spirits, he said, and he feels its influence in psychedelic color and a percussive element in his work, in the rhythm of brush strokes and colors.

His paintings in color have an open-ended energy and movement, he said, like an optical illusion, like a magic eye — change your focus and different images will emerge. They play on the human tendency to see patterns that don’t exist, he said like faces in clouds. When he introduces symmetry and mirroring patterns, they will invoke figures, points the mind will read as faces. When iPhoto first came out with software to recognize faces within photos, early on it would pick out faces in his work.

Some of his paintings can seem more spare on a first look. One of his four paintings at the Clark is black and white. When he sets it in a solo show along with others, he said, he thinks of it as a way of managing silence — it’s been said that music is a way of managing silence.

“It’s about limitations,” he said, “how far I could push a very basic material — I painted it with less than a tube of paint. There’s a tradition of lack of materials in Haiti, conserving as much as possible. And there are different things you can play with when you’re limited — attention span, time spent, softness, the amount of pressure you apply.”

In some places here, his touch is very light, and the surface is almost bare of paint. He feels a push and pull in it, a sharpness and bluntness. He sees a tendency to abstraction in Haitian art, he said, as in Haitian music, even if the art world has not defined it yet. He finds a kind of deep abstraction in elements of Haitian history and culture.

“In Haiti during the revolution,” he said, “there was a perspective on race, that it became abstracted. Early in the revolution, Napoleon sent in Polish soldiers, and in the course of the struggle many of them switched sides and fought for the Haitian people. And after the revolution, the leaders of Haiti granted them Blackness. … A town still exists, called Cazale, with Polish Haitians.”

So he sees layers in his own abstractions, sometimes architectural and map-like, and yet also historic, human and organic. He brings out some of these stories in their names — Wanga Nights, named for a hummingbird. Canapé Vert, a green seat, sounds like the top branches of trees or the ridge of a tropical forest, but it is also the part of Port-au-Prince where he was born, and where his grandfather lived and died.

And Kafou, also named for a neighborhood within Port-au-Prince, comes from carrefour or four corners, a crossroads. In Vodoun practice, it is an in-between point and a holy place. People leave offerings there, between worlds.

Congratulation for Tomm’s show. I knew his grand father vey well. I am an art historian whose focus in on the Caribbean, particularly Haiti, where I was born. I moved to Quebec city, Canada in 2003.

I often visited your museum because, before Covid, I spent Christmas with family in Lenox MA. I learned that you purchased the painting The Swearing in of President Boyer at the Palace of Haiti, by Adolphe Roehn. I have been studying this painting since it went up for sale at Drouot to determine the exactitude of the details in that picture.

I would also like to correct a statement by my friend Frantz Zephirin who says that abstract art does not exist in Haiti. It’s true that the public is generally attracted to the narrative, therefore to a certain realism. But in recent years, there has been more and more artists working partially or totally in abstraction. As a matter of fact, the first abstract artist of the extended Caribbean was a Haitian: Lucien Price (1915-1963). His first abstractions date back to the late 1940’s.

I am pleased to see your interest in art produced by Haitians or dealing with Haitian subject matter.

Best regards

Gerald Alexis

Thank you Gerald — I am very glad to know about Lucien Price and the growing field of contemporary Haitian arbstract artists, and Tomm El-Saieh’s paintings at the Clark Art Institute are beautiful. One of the joys of being a local writer is having the chance to talk with artists when their work comes to us here. Thank you for being in touch, and I hope your summer is restful!