On a cold, clear morning in a studio in Edo, a man picks up a paintbrush. He remembers a day on the coast at sunrise when the maple leaves were turning crimson. He is in his 30s, and he is beginning to be known as one of a group of artists who travel in the summer and paint in winter. And the scene he is painting will travel the world.

In the 1830s, Utagawa Hiroshige came out of a tradition of Japanese woodblock printing that inspired generations of artists in Japan and influenced Western artists from James MacNeill Whistler to Vincent Van Gogh.

“Japanese Impressions” at the Clark Art Institute in Williamstown explores his tradition, the artform of Ukiyo-e, and the forms that have grown from it, in 73 prints across 150 years.

The show celebrates a gift to the Clark from Adele Rodbell, who has served as a docent at the Clark for almost 40 years, said Jay Clarke, Manton Curator of Prints, Drawing and Photographs. (Forty-eight prints come from from the Rodbell Family Collection, along with works on loan and prints from the Clark’s permanent collection.)

Ukiyo-e began as a style of woodblock prints and paintings of beautiful women, kabuki actors and sumo wrestlers, scenes from folk tales and travel. The name means “pictures of the floating world.”

It was a world of pleasure. In the 17th century, the Japanese government moved from Kyoto to Edo (modern Tokyo), and merchants gained in class and in wealth. A middle class was rising, Clarke said, and they enjoyed kabuki theatre, courtesans and geisha.

This kind of bright, intoxicating performance, and sometimes escape — like the Montmartre cabarets in Toulouse-Lautrec posters — became Ukiyo, the “floating world.”

Wood blocks could make copies of a print, she said, and even limited edition prints skillfully made by hand were inexpensive enough for traders in Tokyo — and artists in Paris.

In the 1830s, as this show picks up the thread, some of the best-loved artists in the genre were moving the form in new ways. Katsushika Hokusai is still known for The Great Wave from his series of Thirty-Six Views of Mount Fuji. This show includes a work from the same group, The Surface of the Lake at Misaka. Light touches the mountain ridge, and the reflection in the water is capped with snow.

Hokusai and Hiroshige shifted their focus from city pleasures to landscapes and people living daily lives. In this show, Clarke contrasts their work with comic scenes from Edo,

tipsy musicians or a man falling on ice with his robe flying around him.

In Hiroshige’s prints, the fine texture and shading of color, detail in the land

give a deeper feeling for the places and the people he sees.

To reproduce those effects, he needed a gifted printer, Clarke said. In his time, one artist created the image (and usually got the credit). Another artist or artisan would transfer the design onto the wood block, and a printer would create the image on paper, both by hand. They had techniques for texturing the paper and blending colors.

The publisher would fund the work and often suggest the idea for it, she said. Many of these images come from travel series — A Tour of Waterfalls, Eight Views of Omi. But the artist could interpret perspective and light and color.

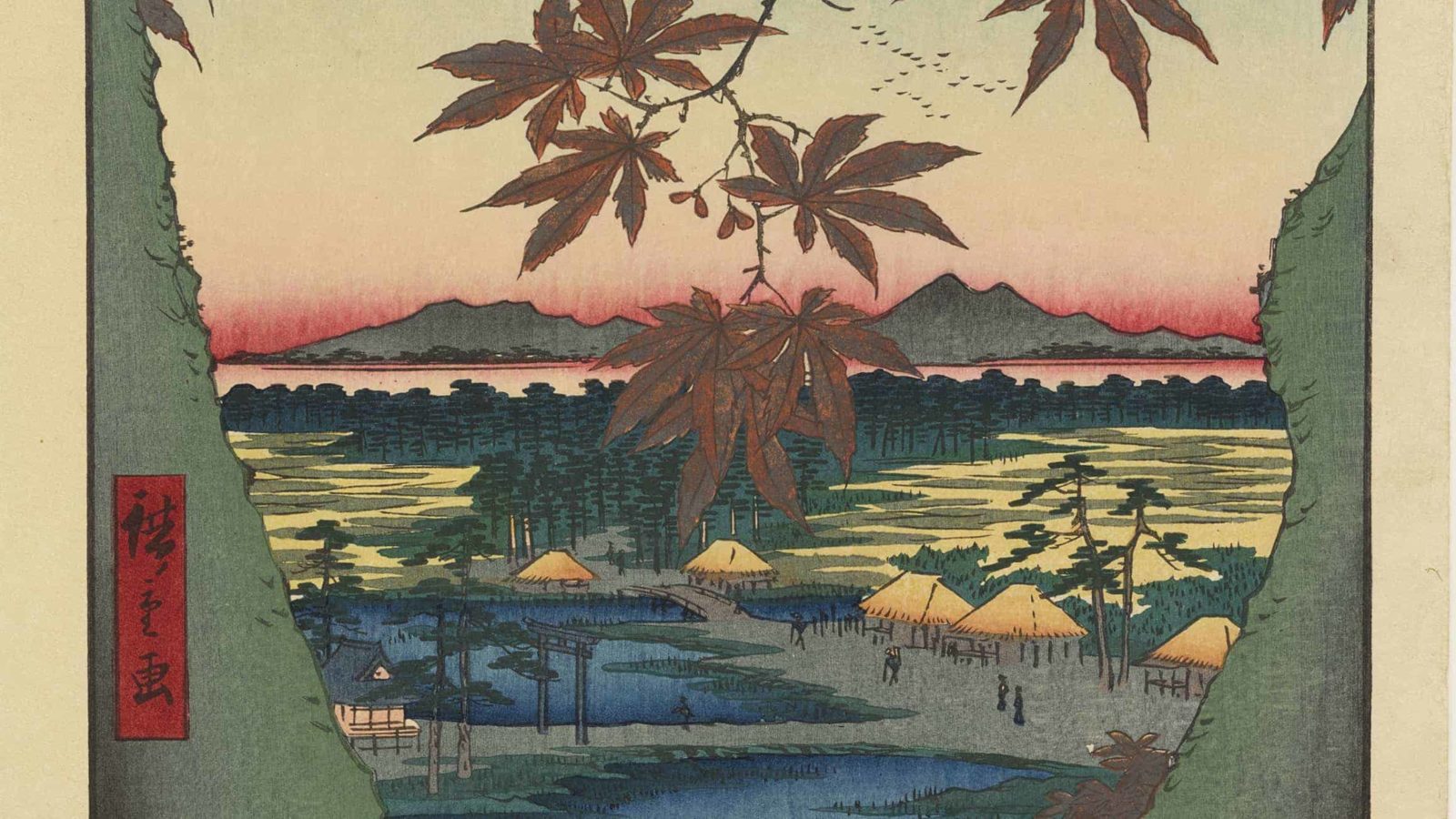

Hiroshige often places a large element in the foreground, like a branch of red maple leaves, that catches the eye. On a closer look, the eye moves past it into the distance.

This is not the perspective so common in Western art, she said, when the image draws the eye to one point in the distance. Hiroshige influenced many artists in the West.

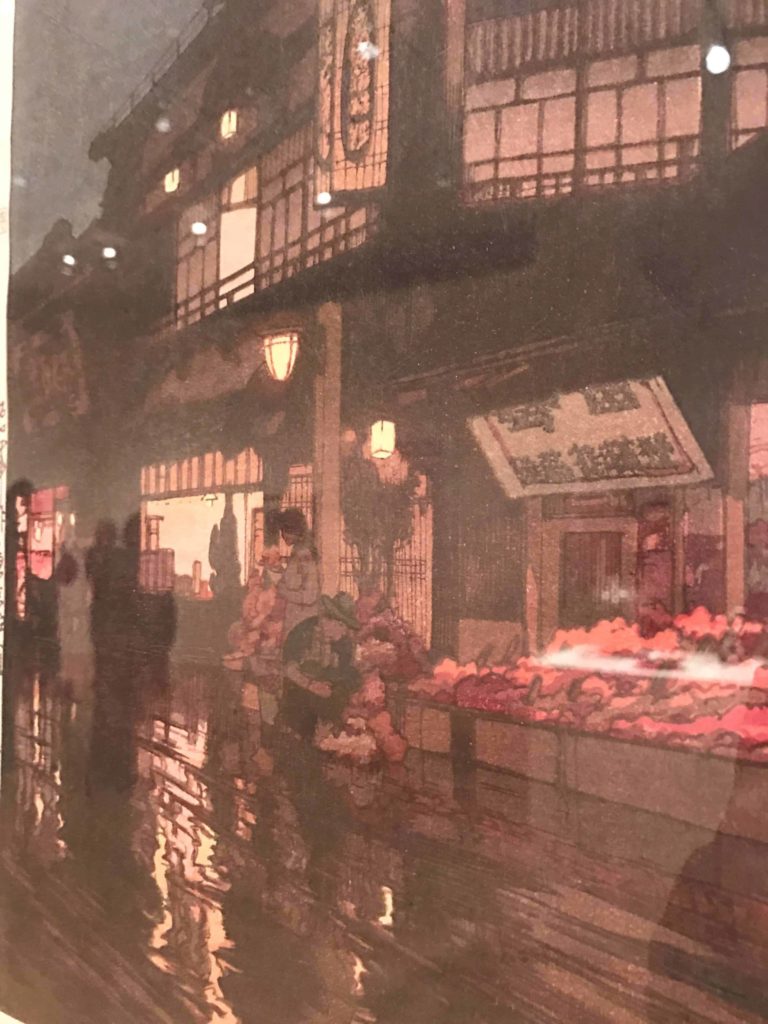

And artists in the West began to influence Ukiyo-e. Western elements of realism and perspective appear in the work of early 20th-century artists like Kawase Hasui, in the shading of houses in the snow at dusk.

Yoshida Hiroshi traveled the world, Clarke said, from Europe to the American West. The distant roofs in his Itoigawa Morning could have been a small town in the Rockies. And on his Mount Fuji, almost 100 years after Hokusai’s, ice seams the rock like veins in marble.

In Ito Shinsui’s ‘Katondo applying makeup,’ a woman looks thoughtful as she smooths powder onto her bare shoulder. He painted her in 1922, a lifelike woman with intelligence and self-possession in her look and movement. Clarke sees the influence American Impressionist artist Mary Cassatt in her — she sees Cassatt looking at Hiroshige and Shinsui looking back at her.

Printing techniques had evolved in the last century, but in the 20th century, traditional hand-printing returned. The Shin-hanga Movement countered the interest in Western culture with a growing value for traditional Japanese culture and art.

And in the early 1950s, the Sōsaku-hanga Movement drew again on the ukiyo-e tradition with a flavor of Modernism. Artists like Kiyoshi Saitō took over the carving and printing themselves. He renders rock gardens and Buddhist architecture with abstract shapes, solid colors and the texture of grain in the wood.

Finally, out of this respect for work by hand came Mingei, the Japanese arts and crafts Movement. Among her impressions, Clarke has included ceramics by Shōji Hamada, one of the founders of Mingei.

He was a national living treasure, like Hasui, and like Tadao Ando, who designed this building, where the walkway follows the granite wall and then opens into a wide courtyard and reflecting pool, with Stone Hill behind.

His spaces take time to enter, Clarke said, like Hiroshige’s. Come close to a bright paper lantern swinging in the wind, and look past it to a crowd of people, small in the distance, walking to a temple in the snow.

This story first ran in the Berkshire Eagle; my thanks to Arts & Entertianment Editor Jeff Borak. At the top, Hasui’s image of Tennoji Temple appears in ‘Japanese Impressions.’ Image courtesy of Clark Art Institute