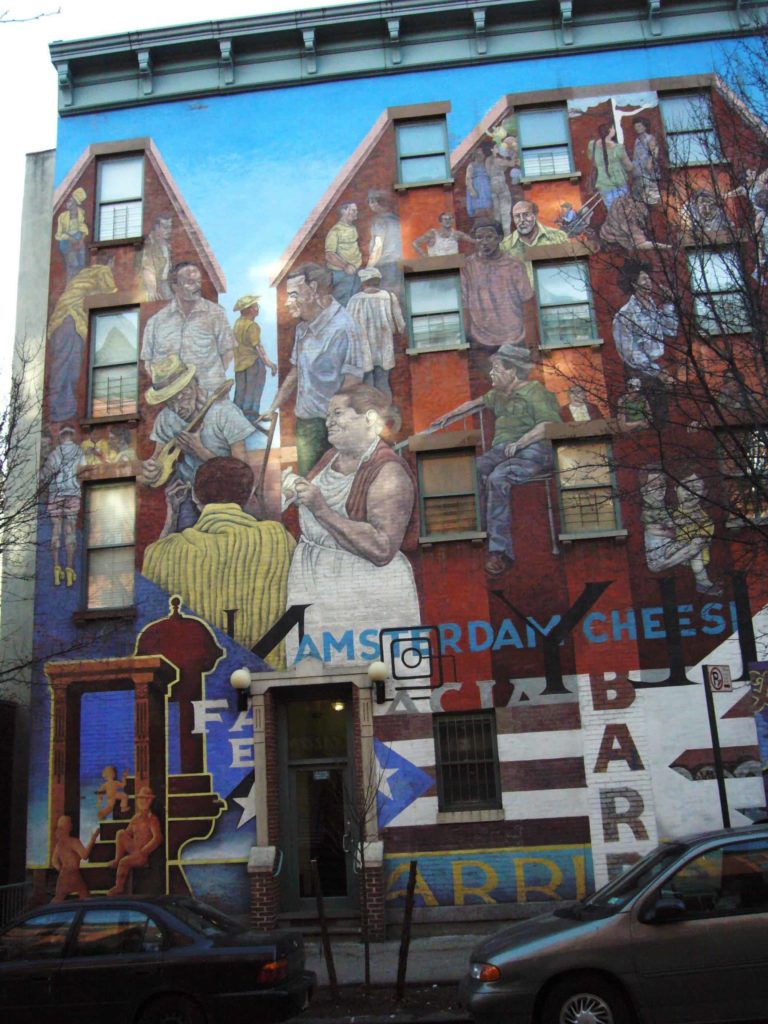

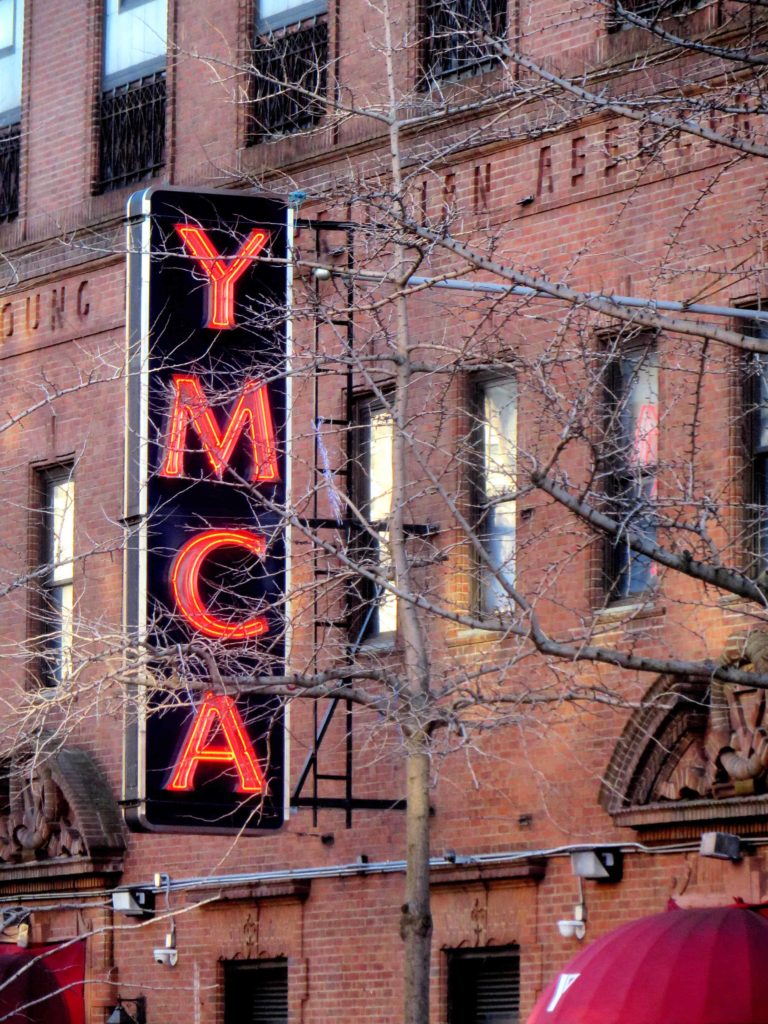

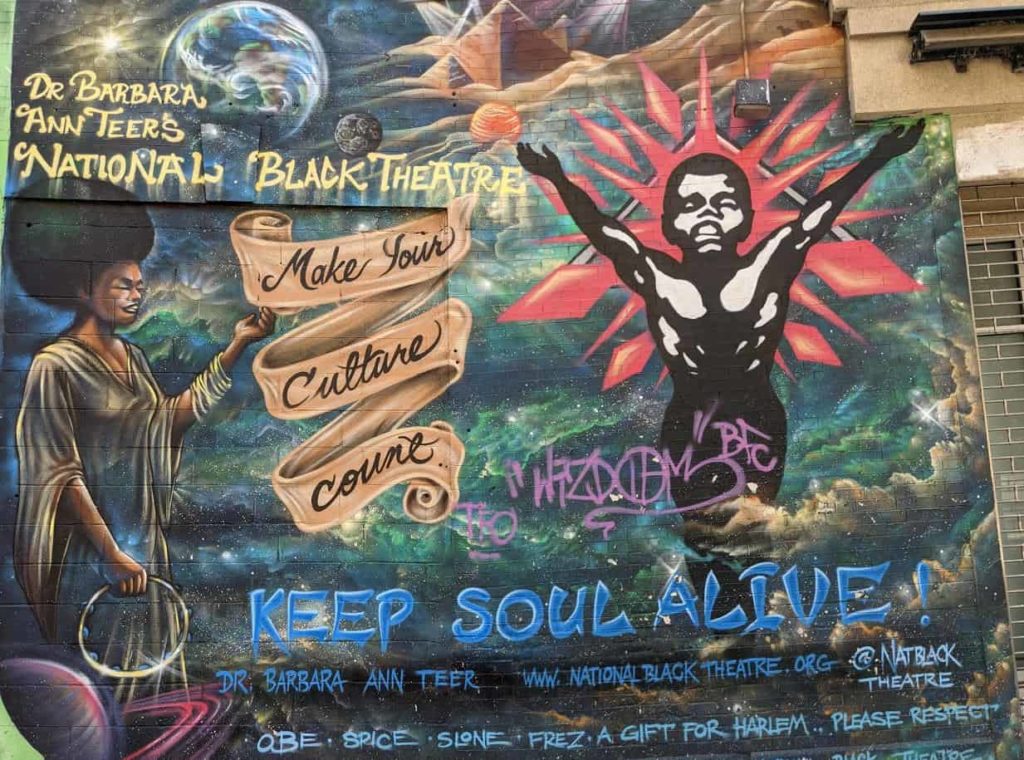

Near his photography studio in Harlem, James Van Der Zee could have heard Bessie Smith and Ma Rainey sing the blues. He could have stood before Aaron Douglas’ murals at Club Ebony and the 135th Street YMCA and taken in their translucent abstract color and the energy of people dancing in the city night or walking at the edge of the woods toward the sunlight.

And he could have studied with Augusta Savage at her studio on West 143rd St. and admired her commission at the New York Worlds Fair. She sculpted a harp formed of men and women singing together; their robes fall in serene folds, like harp strings.

Van Der Zee lived in New York at the height of the Harlem Renaissance in the 1920s and 1930s. In the generations after the Civil War and Reconstruction, this was a surging time of creativity among black artists, writers and musicians. And Van Der Zee photographed that movement.

In winter 2019, the Williams College Museum of Art celebrated a collection of his photographs spanning 33 years and brought it home.

He was born here, in Lenox, and grew up in a close family of artists and musicians and entrepreneurs. When he came to New York in 1906, looking for a job, he was 20 years old and already skilled with a camera. To make a living, he and his second wife, Gaynella Katz Greenlea, opened a photography studio on Lenox Ave. in Harlem.

Through the 1920s and 1930s, he created portraits of his community — young couples, families, artists and professionals. He worked with them to create an image they wanted to project into the world, said Kevin Murphy, senior curator of American Art at WCMA, who has co-curated the exhibit with WCMA’s Assistant Curator, Horace Ballard.

Van Der Zee would help them to show who they were — a young bride and groom in their wedding finery, or friends basking at the beach. They look out of his portraits, beautiful and confident and prosperous.

“He has a great eye for detail and a sense of place,” Murphy said.

WCMA has had one of his studio portraits for years. A young man in an active duty uniform sits at a desk by a window, and above him like an afterimage floats a sketch of a World War I soldier standing by a grave.

The museum has been working to add to their collection of Van Der Zee’s photographs for some time, Murphy said; they collect the work of contemporary African American artists, and they are bringing in more work by black artists in the 20th century and earlier. In 2017, he helped to find a portfolio of 18 of Van Der Zee’s photographs taken between 1905 and 1938.

Van Der Zee reprinted them in 1974. He was 88 then. His career had seen a new surge, and he chose these images to represent it.

Light and cloud dapple a blue sky above the arches of a building in Harlem, N.Y. Creative Commons courtesy photo

The museum will show them and the works in its collection, along with writings and objects that Chapin Library has also collected.This is not a full retrospective, Murphy said — it is a close look at the highlights Van Der Zee chose.

In them, he sees Van Der Zee supporting his community, taking note of politics and social movements, and publishing The Harlem Book of the Dead with the poet Owen Dodson. A family would bring Van Der Zee to take a last image of a loved one before they were buried, and he interleaved these images with verses.

In the portfolio he includes an artistic image, a nude woman sitting by the hearth. She is looking into the fire with her arms folded around her knees, and he shows her from the side, with her face in the firelight and her hair in shadow.

With silver gelatin plates, he could also add effects in the darkroom. He became known for double exposures, a technique that sets a translucent image over the clear and solid photograph, like a ghost or a dream.

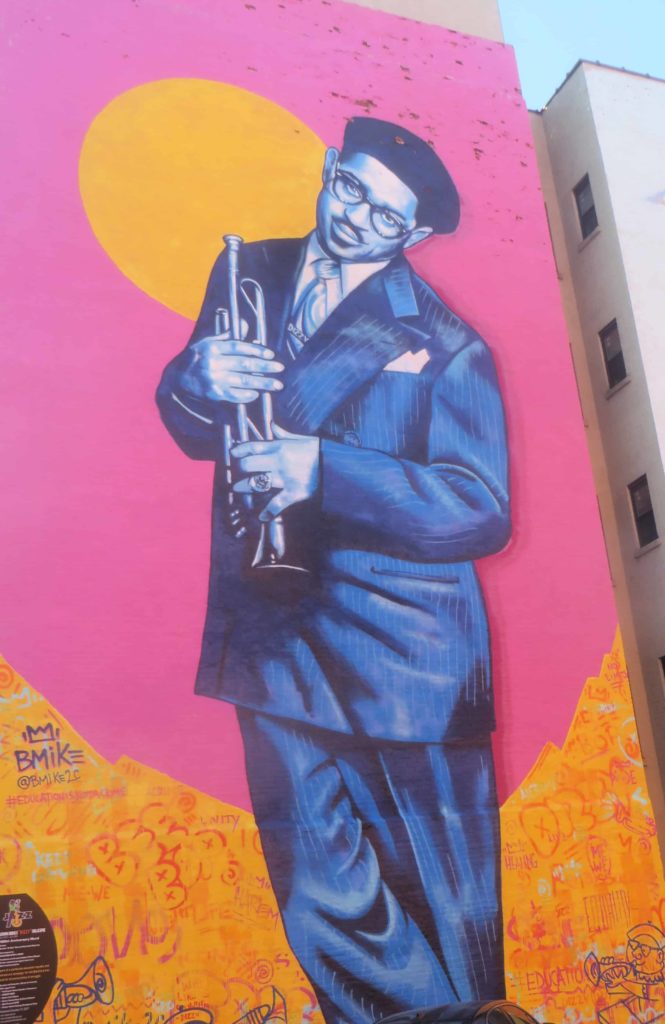

Dizzy Gillespie plays his horn with students, floating in a blue sky, in a mual by Marthalicia Matarrita in Harlem, N.Y. Creative Commons courtesy photo

But many of the images here are commissions. In the 1920s and 1930s, few people had their own cameras, Murphy said. They would come to a photographer to commemorate an occasion — a wedding, a memorial, an accomplishment.

Van Der Zee took family groups and solo portraits of dancers and actors. He could set up backdrops, costumes and props, Murphy said, like the contemporary Instagram photographers in Possible Selves (also on view now) who take self portraits with carefully designed lighting, flowers and compositions to present and explore an identity.

In Van Der Zee’s portraits, African-Americans appear as a rising middle class in the city, well-educated and professional and sophisticated.

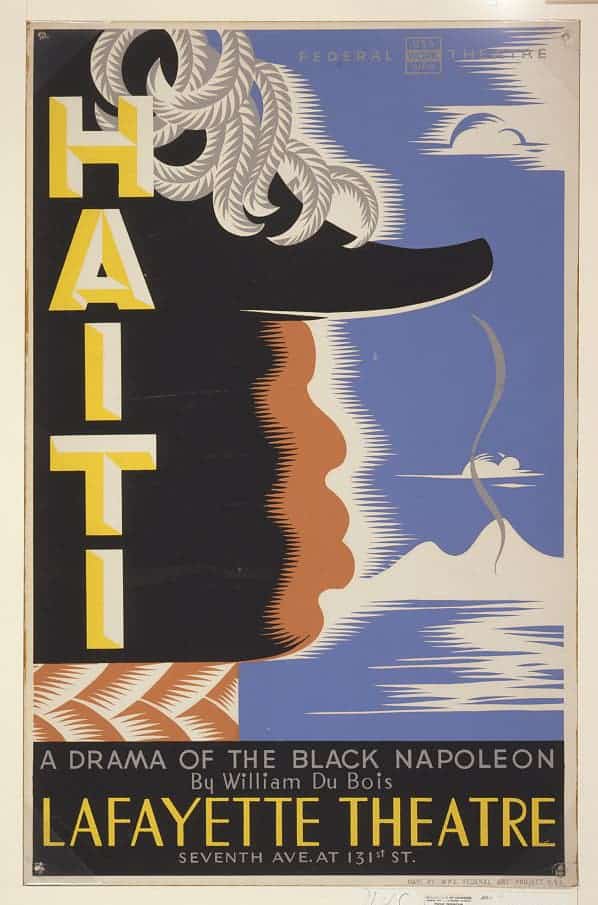

Haiti, a drama of the black Napoleon, by William Du Bois, Lafayette Theatre, by Vera Bock, 1938 Work Projects Administration Poster Collection from the Federal Theater Project No known restrictions on publication.

His portfolio reveals the community around him. The members of the Moorish Zionist Temple of the Moorish Jews at 127 West 137th St. come out on a sunny day to stand on the steps in their sabbath day suits and dresses, with the rabbi in his tallit.

In another image a woman sits poised behind her piano in a high-ceilinged room with paintings on the walls. Van Der Zee calls her “the Heiress,” Murphy said, suggesting a legacy. Her family hands on traditions and resources across generations.

And here is a couple in long coats standing on the curb by their Cadillac coupe in 1932. Even during the Depression, Murphy said, they were flourishing.

Times changed.

After World War II, with Brownie cameras and 35 millimeter film, people could take their own pictures. The Van Der Zees found the world of photography shifting around them, and they struggled.

And then in 1969, Van Der Zee’s work became central to an exhibit at the Metropolitan Museum of Art called ‘Harlem on My Mind.’ It was a controversial exhibit, Murphy said, and for good reason. At the height of the Freedom movements, in the months after Martin Luther King’s assassination, it showed photographs of African-Americans, but no other artwork by them.

The curator refused to include paintings, prints or sculpture, or to talk with black artists and writers and take their views into account, and the show became less an art exhibit than a sociological study. It drew widespread protests.

And it introduced Van Der Zee’s images to an international audience.

By the 1970s, he and his wife were struggling with her last illness, and people beyond the city and the country knew his name.

When he put this portfolio together, he knew grief and anger, but if the strength in these images is a guide, he could look back at those earlier years in Harlem with warmth and pride.

This story first ran in the Berkshire Eagle in January 2019. My thanks to Lindsey Hollenbaugh and Jennifer Huberdeau.