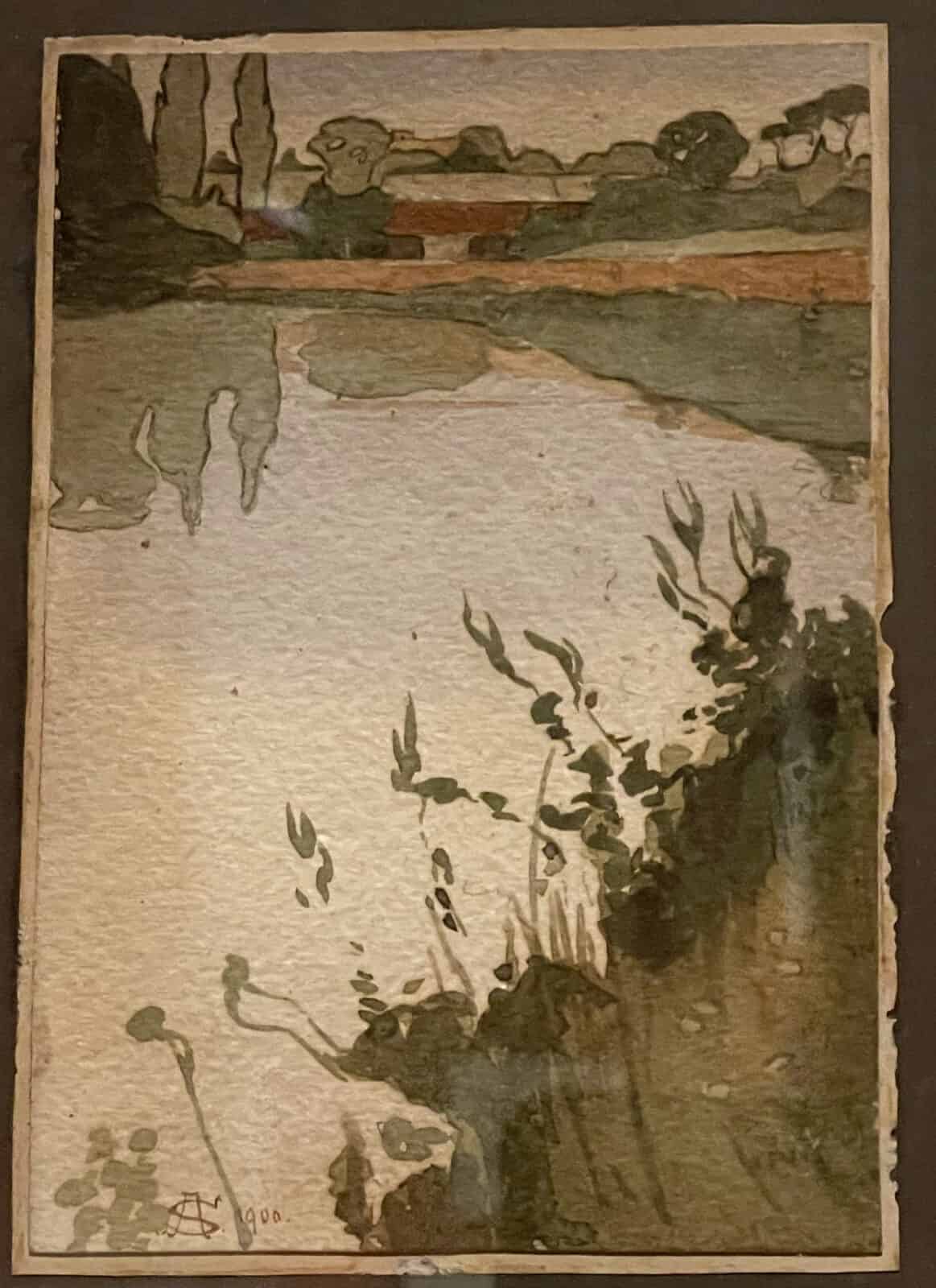

Sheep are grazing in Mainz in the shade of cypress trees. Whitewashed cottages flank a dooryard in Volendam with tall peaked red roofs. It’s easy to imagine the artist who painted the watercolors, traveling German backroads the way someone in the Berkshires might stop at a pulloff and take out their Smartphone.

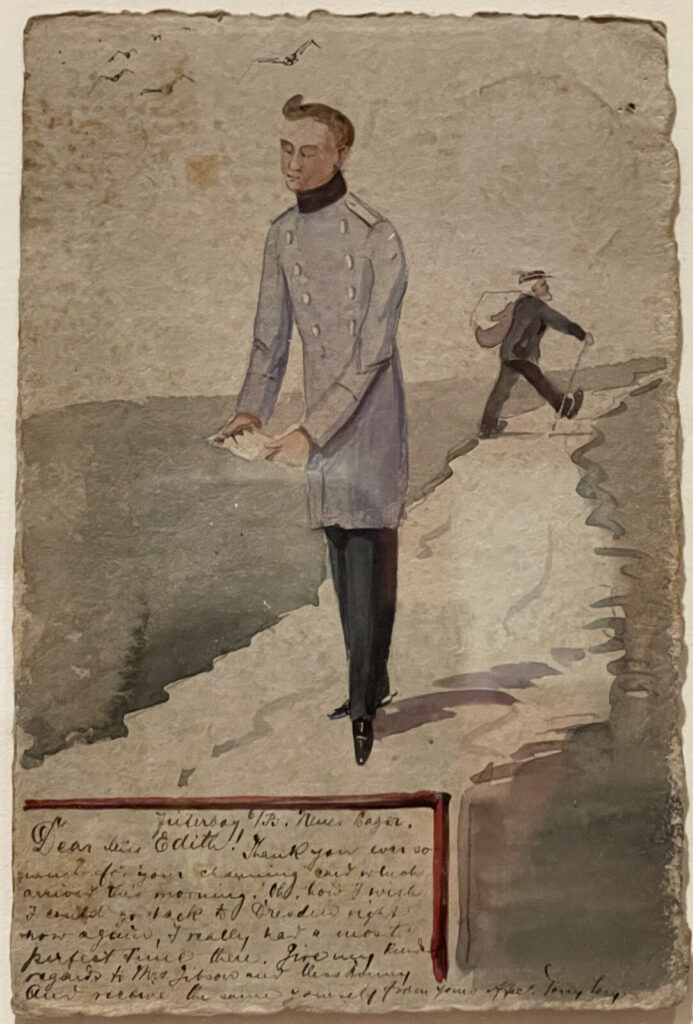

Here he is, a young man in a grey wool coat with a double row of buttons — a student in a military academy at 14, a Lieutenant at 17. He’s sketching a river at dusk with a barn in the distance and summer growth along the bank.

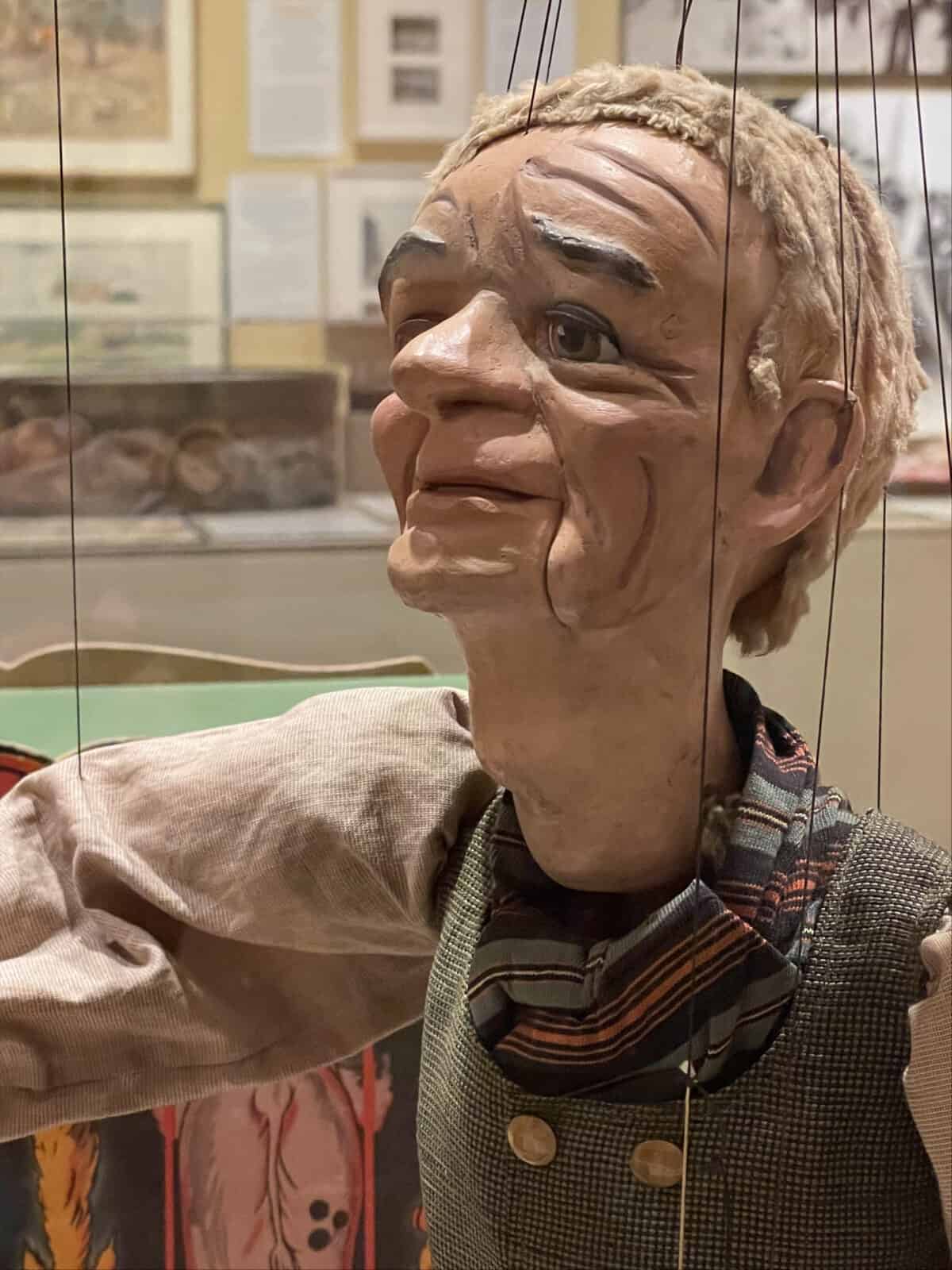

A puppet with eyebrows and ears suggestive of an elf or a firefly joins Tony Sarg's puppet theater cast of Pinocchio, with Sarg's artwork on the wall behind. Press photo by Kate Abbott, courtesy of the Norman Rockwell Museum

Tony Sarg has come a long way to reach the Norman Rockwell Museum this summer. An artist and illustrator in London before World War I, and in New York from the 1910s to the 1930s, he has influenced puppetry across America for generations — even to the Muppets.

In his lifetime he became known across America and beyond for his marionettes, says curator Stephanie Plunkett. As a showman and an entrepreneur, he has had influence behind the scenes.

In a retrospective show, the museum takes a close look at his life and his influence, as a complex, humorous, innovative and sometimes challenging character. Plunkett came across his trail in Washington D.C., she said, walking through the museum galleries.

On a trip to speak at George Washington University museum, she and curator Lenore D. Miller discovered a shared interest. Plunkett knew Sarg as the originator of the mammoth balloons in the Macy’s Thanksgiving Parade, and in a spirit of curiosity, she and Miller began to research his life.

His story begins in the 19th century with a dissonant note of Colonialism and takes him to Greenwich Village, across three continents and two World Wars. He was born in Guatemala in 1880, Plunkett said. His mother was English, and his father was a German diplomat and son of the owner of a coffee plantation in Alta Verapaz.

The show opens with a recognition of a beautiful place and a painful past. In the 1800s, white European and American planters in South America often ran coffee plantations with forced and conscripted labor.

Sarg lived on the plantation in his earliest years. By the time he was seven, Plunkett said, his family had moved to Germany, to a center of industry and science near Frankfurt, and at 14 Sarg was attending a military academy south of Berlin.

Tony Sarg painted watercolors of the landscape as a young man in Germany. Press photo courtesy of the Norman Rockwell Museum

On the home front

Even in the army, Sarg was painting and illustrating fairy tales. The show opens with his early watercolors, and the catalog gives sketches from a letter to an American visitor, Bertha McGowan.

He wrote her that his youngest sister, Lotty, had eloped with a musician — his father had cut her off, and he was trying to help her. His sister Florence was sick, enough that a short walk exhausted her, and he had lost most of his savings in a loan to an artist who couldn’t repay him.

Sarg took on his own share of family tension, Plunkett said. He resigned his commission in 1905, over his father’s protests, and by 1909, he and Bertha had married and moved to London. He set himself to paint and draw, and while he was self-taught, he found work.

He kept a studio in the Old Curiosity Shop, she said, a building named for Charles Dickens’ internationally best-selling novel. The book was so intensely popular that people would come looking for the room where the fictional heroine, Little Nell, used to live — and so Sarg created a room for them, a theatrical design somewhere between a tourist whimsey and an art installation.

Creative assignments fanned his interest in marionettes, Plunkett said. For the London Sketch, Sarg went to see Thomas Holden’s puppet theater, on tour through Europe and Asia and the U.S.

“He wasn’t allowed behind the scenes,” Plunkett said. “Puppeteers guarded their craft closely.”

Sarg went to performances repeatedly to study the puppeteer’s effects, and he began to experiment with the wooden handgrip that holds and moves the strings. The subtlety of the puppeteer’s movements give the puppets nuance and grace, he recalled in the show catalog, and he felt the performers could do more.

“Although the Holden marionettes were excellent mechanically, they were not handled by an artist … I could see great possibilities the Holdens were completely overlooking.”

‘(The puppets) were not handled by an artist. I could see great possibilities the Holdens were completely overlooking.’ — Tony Sarg

And then 1914 transfigured the landscape. World War I thundered down, and anti-German sentiment rose in London. By 1915, Sarg and his wife and their young daughter, Mary, had moved to New York. And his puppetry took off in earnest.

They came to a city where Italian communities were performing Sicilian opera dei pupi in Little Italy and Red Hook, and puppetry had captured attention from Bohemian life to Broadway, John Bell explains in his introduction in the show’s catalog. Marionettes entertained children, and they played an equal role in experimental and original art.

At the Neighborhood Playhouse, one of the first Off Broadway theatres, where Sarg opened his first U.S. shows, Remo Bufano was performing with Sicilian rod puppets puppets, and he created life-sized and miniature marionettes for an avant garde opera, El retablo de maese Pedro. (Andalusian composer Manuel de Falla wrote the music based on a scene in Miguel Cervantes’ Don Quixote, when Quixote sees a puppet play and becomes so fascinated he tries to intervene in the action.)

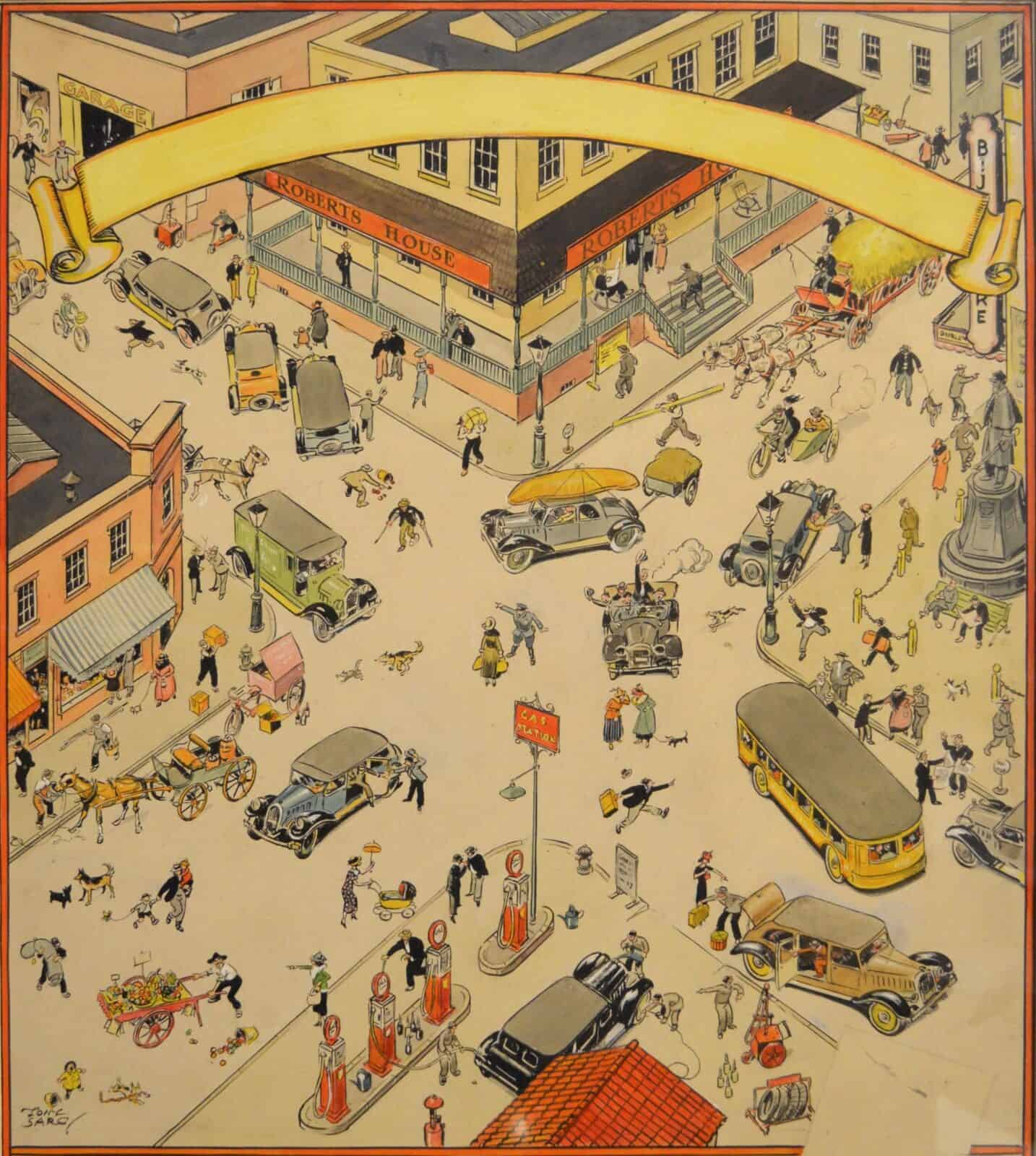

An intersection fills with traffic of all kinds in Tony Sarg's illustration of early 20th-century New York. Press photo courtesy of the Norman Rockwell Museum

New York in the Roaring ’20s

Tony Sarg’s New York was the New York of Norman Rockwell’s fellows — artists at the Salmagundi and the Dutch Treat Club, Ogden Nash, Ring Lardner ….

And when he set up his studio, his neighborhood held a wider circle of creative people. Greenwich Village in the 1920s was ‘a refuge for undiscovered artists and free thinkers,’ (says the Library of Congress archive — and check out photo #7 in See Old NYC …)

This is the Village of Edna St. Vincent Millay and E.E. Cummings and Margaret Sanger — suffragists and activist and jazz clubs where Duke Ellington, Louis Armstrong and Bessie Smith performed …

Sarg opened his own marionette studio in Greenwich Village, and he and his wife made puppets by hand. He quickly formed his own troupe of marionettes, and by 1917 they were performing William Makepeace Thackeray’s satire on the aristocracy, The Rose and the Ring, on Broadway. He found powerful collaborators, Bell says: Playwright Hettie Louise Mick wrote the script, and Ellen van Volkenberg, co-founder of the Little Theatre of Chicago, came in as artistic director.

She influenced the puppets’ movement, character and style and encouraged him to create his own company. Sarg seems to have worked often with women artists and performers, as he moved from one venture to the next. Men and women worked together in his puppet troupe, Plunkett said, as they did in his artistic crew.

Sarg sent traveling shows across the country, and by 1927, his influence reached the Macy’s parade. He thought of balloons as puppets turned upside-down, Plunkett said, looking at a black and white photo of artists in his workshop, up on ladders. They would begin with the rubber shape and then lay on the color.

Rufus and Margo Rose, members of the Tony Sarg troupe, created a Gepetto marionette with their own puppet theater cast of Pinocchio kneels in profile with Sarg's artwork behind him. Press photo by Kate Abbott, courtesy of the Norman Rockwell Museum

Performance for the people

The Neighborhood Playhouse opened in 1928 with luminous artists and teachers like Martha Graham and Agnes DeMille. it took shape as part of a national Little Theatre movement — in cities across the country, theaters formed to create and present intimate, open-minded work within communities.

The Neighborhood Playhouse is one of them. It opened in 1928 in the Henry Street Settlement, a community center that formed in 1892 to bring healing and care to the communities of the Lower East Side — and it still does.

And Sarg was already moving on — he opened toy stores, illustrated maps, performed at two World’s Fairs. Sometimes the speed of his juggling came at a high cost, Plunkett said. In 1939, on the edge of another World War and two years before he died, he declared bankruptcy. He gave some of his marionettes to his troupe in payment of debts, and others were sold.

But he supported the artists who worked with him, even through the Depression, and they honored his influence. Puppeteers in his troupe would go on to form their own national impact. Margo and Rufus Rose toured the country. Sue Hastings formed one of the largest puppet companies in the U.S.

Bil Baird became a household name, performing the lonely goatherd and the puppet goats in the Sound of Music … and he influenced Jim Henson.

Visitors to an art gallery show a myriad of human responses in Tony Sarg's 'Humours of London.' Press photo courtesy of the Norman Rockwell Museum

A bird’s-eye view

Whimsy often comes through in Tony Sarg’s work, in comic scenes for German and English publications and the London Underground, and later in New York. Before cameras took hold, llustrators were the photojournalists of the day, and Sarg captures cartoons with fluid lines. Looking at work now, Plunkett sees a kinship with the New Yorker in his line drawings, fast-moving ironic views on the street.

He became known for scenes in the city from a bird’s eye view, the same view a puppeteer would have of marionettes on a stage.

intense action and vignettes — in a gallery at the Tate, fashionable couples admire the paintings, a boy stares in fascination at a nude statue, a man pats a small dog, in the foreground a bohemian woman in trousers and a blazer looks around smiling with her hat in her hand …

Tony Sarg visits his puppeteers and captures the landscapes of Germany in watercolor — and New York in print.

Hydrangeas bloom at the Norman Rockwell Museum on a sunny summer day.