Seventy-five young men, as young as 12 or 14, are looking out the train windows at fields and stone walls, and streets lined with elm trees. Sheep are grazing almost to the top of Mount Greylock. Pasture and charcoal have stripped the hills bare.

Everything looked and smelled and tasted new to them. Many of them would not eat the train food. These teenagers had all newly come from China to North Adams, and only one spoke English.

“How could they trust anything from the hands of these foreigners with the complexion of the shark’s belly, whose men and women sat across from each other, their shoes touching? … A woman at the first stop had touched her mouth by way of greeting another descending from the train.”

Williams Professor Karen Shepard describes them in her novel, “The Celestials.” Her story is historical fiction, and the young men were real. They came to North Adams in 1870 to work at Calvin Sampson’s shoe factory. Samson brought them in to break a strike. They came to work, to earn and save money, so they could return home.

“The Celestials” deals with questions wringing the country, said Sharon Hawkes, executive director at the Lenox Library — with immigration, assimilation and acceptance.

New York artist and muralist Gaia has painted a mural in honor of Lue Gim Gong, horticulturalist and Celestial, who came from China as a young man and worked in the mills in North Adams before moving to Florida.

“I didn’t plan that,” Shepard said, “but while I researched it, I would listen to the news and think, ‘Have we learned nothing?'”

As she wrote, her novel began to sound sharply, sometimes painfully familiar. North Adams in 1870 was a sealed place, she said, held in a valley. But the mills were running full-speed ahead. They were changing, as machines took on more work and the mill owners no longer needed workshops of skilled craftsmen.

At the shoe facgtory, Sampson was facing off against the Knights of St. Crispin, the union persuading all non-union workers to leave his mill.

The strikers were mostly Scots or Irish, and newcomers themselves, and they had made enemies in the town. Shepard shows them refusing to work with any man who would not join the Crispins and driving men violently out of town.

Samson responded by bringing Chinese workers into his mill.

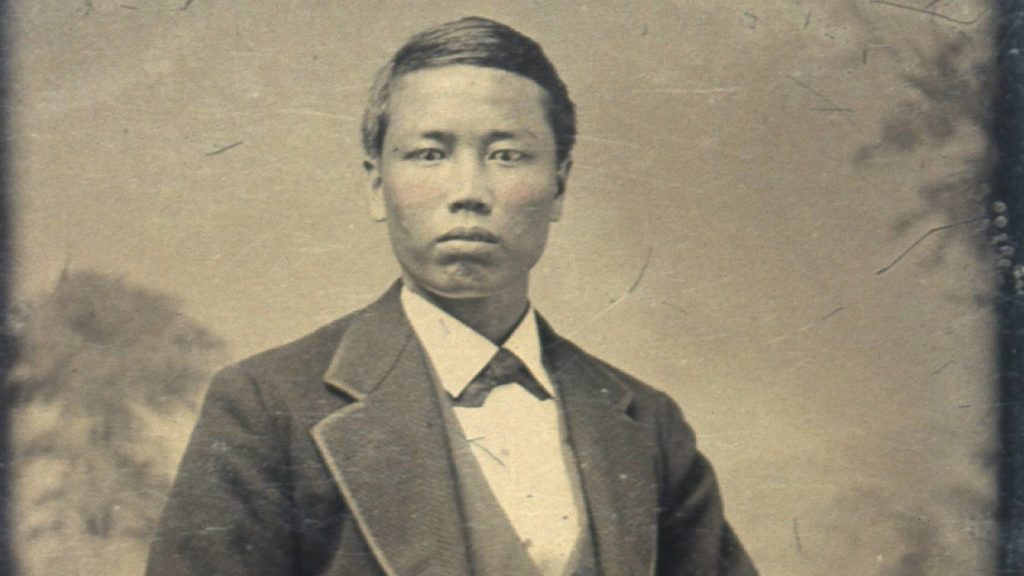

Shepard first felt their story take hold of her at a talk by art historian Anthony Lee, who teaches at Mount Holyoke College. She had known about the strike breakers, she said, but she had never seen the Celestials, the Chinese workers who came to work a the factory in this upheaval. She looked at a photograph of young teenagers lined up against a brick wall on their first day in North Adams, while armed guards around them held guns, keeping the strikers away from them.

She left the talk thinking about the power of the Celestials’ story, she said. It took her longer to feel that she needed to write it.

She and Lee shared research, she said, and she came up against limitations. She could read accounts of what a shoe-making factory in the 19th century looked and sounded like, but the Celestials had not written their own impressions.

She drew from the experiences of many people like them, and from “How do you deal with Americans” books written for Chinese immigrants — and from her own experiences. Her mother is Chinese, and when she was 6, Shepard visited China with her mother.

“My presence was so foreign to the kids there,” she said. “I looked Chinese, but not enough. I had a camera.”

She would be surrounded by children who wanted to touch her, to touch her hair. That feeling, that glimpse of what a world she was unfamiliar with thought of her, stayed with her.

Mass MoCA presents The Celestials, a performance based on Karen Shepard's novel.

In North Adams, the celestials stayed with local families, she said. Local families mentored them, taught them English and tried to convert them to Christianity.

In their photographs, she said, she could not put names to faces. Only in two cases could she look at a man and know his name or his story.

Charlie Sing, the foreman and the only Celestial who spoke English in the beginning, becomes a central figure in Shepard’s novel. Lue Gim Gong also worked as a gardener for the Burlingame family in North Adams.

The Celestials lived and worked in North Adams for 10 years, to the end of their contracts. And then most of them returned home. But their leaving did not mean Sampson’s idea had failed, she said. He broke the strikers and the union, and when his Celestials finished their contracts, he invited more to come.

In fact, Sampson’s idea worked so well — for the mill owners — that it had sweeping effects. The Chinese workers kept Samson’s mill running and gave him leverage against the unions. As this kind of arrangement became more common, white U.S. workers protested, until the U.S. banned Chinese laborers. President Chester Arthur signed the Chinese Exclusion Act in 1882, deporting Chinese workers and forbidding them entry to the country. The act remained in place until 1943.

Shepard has given voices to the people this country kept out for so long, and she has made their stories her own.

‘While I researched it, I would listen to the news and think, ‘Have we learned nothing?’ — Karen Shephard

Their stories go on past those 10 years they lived in North Adams. Lue Gim Gong’s North Adams family adopted him, and he moved with them to Florida — where he developed a new kind of orange that could withstand Florida summer heat, and revolutionized all of Florida’s orange orchards.

Fanny Burlingame, his adopted mother, was cousin to Anson Burlingame, Abraham Lincoln’s U.S. diplomat to China. In a sad irony, Anson’s work in the 1860s may have allowed Lue Gim Gong to come to the U.S. in 1870 — and Lue Gim Gong’s patient work in North Adams, and the effect of many workers like him, quietly working to save money so they could return home and marry, may have persuaded the U.S. to forbid his countrymen to come here for the next 60 years.

None of the Celestials are still here, Hawkes said, except as headstones in North Adams cemeteries. The Chinese characters carved into them have mostly faded away. But in summer 2021, New York artist and muralist Gaia came to North Adams to paint a mural in honor of Lue Gim Gong that fills the whold side of on a building on the MCLA campus, three or four stories high.