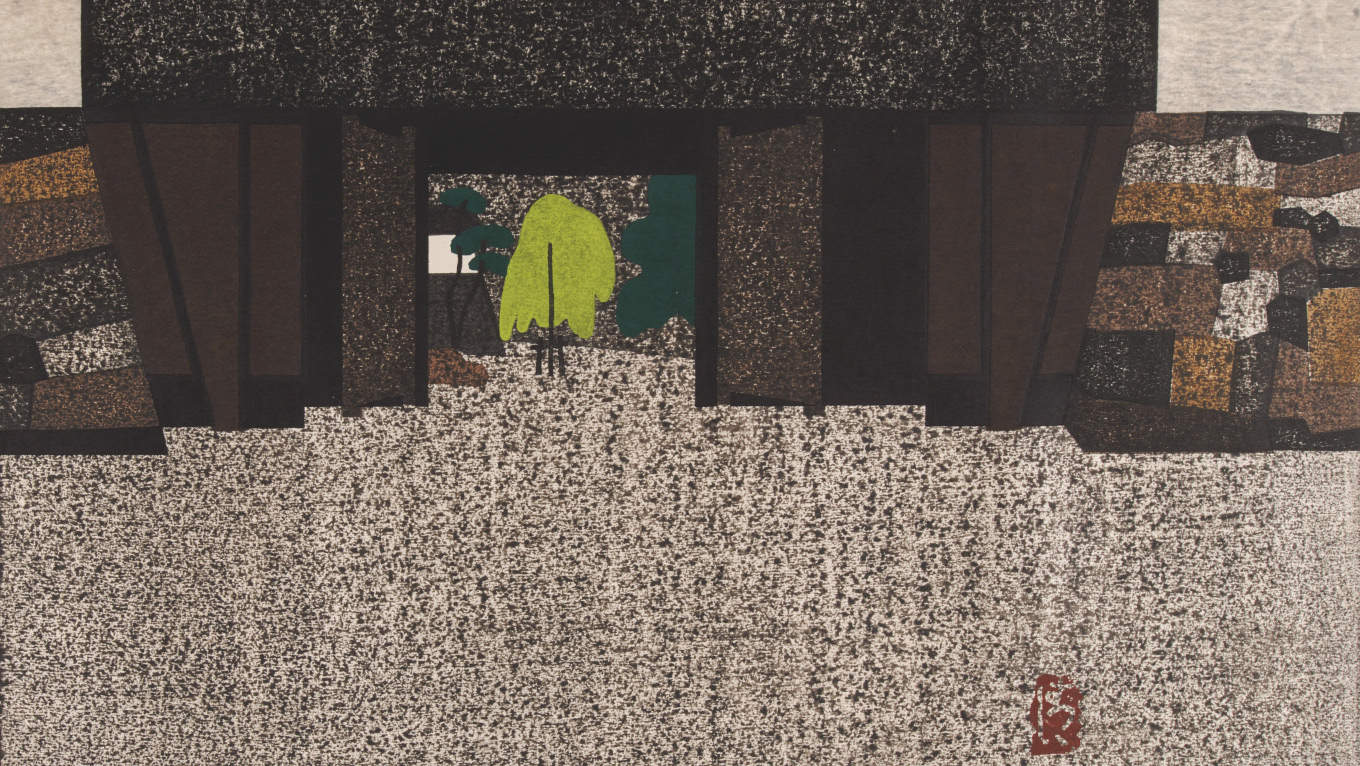

The courtyard spreads in a shifting surface like water or stone. The wash of it draws the eye forward with its perspective. A wall cuts off the view with geometric precision, and through it, on the far side, light is glimmering with a suggestion of wider space. Trees trace fractals of branches against the sky,

It could be the view from the pavilion, across the terrace and snow on the reflecting pool and out over Stone Hill. If this wall could turn translucent, the landscape beyond would have more than a few elements in common with Saitō Kiyoshi’s Sakurada-Mon Tokyo.

They share a solidity of rock. Saitō’s print gives a long view through a gate in the inner moat of the Imperial Palace in Edo. And architect Tadao Ando has set granite around the courtyard at the Clark Art Institute, the same granite in the walls of the Manton Center and the library.

Saitō Kiyoshi's color woodblock print shows the courtyard of Sakurada-Mon Tokyo, 1964. Press image courtesy of the Clark Art Institute

Clouds and sun pattern the sky over Stone Hill at the Clark Art Institute.

This winter the Clark is celebrating half a century of the Manton Center in two new shows that take a broad look at the museum’s collection. In 50 Years and Forward: Works on Paper, the museum ranges across themes and media and time.

Anne Leonard, Manton Curator of Prints, Drawings, and Photographs, has chosen prints, drawings, and photographs that have come to the museum between 1973 and 2023 — and made across 500 years and around the world, from 14th century Florence to 20th century Japan, from Paris to New York to Yosemite.

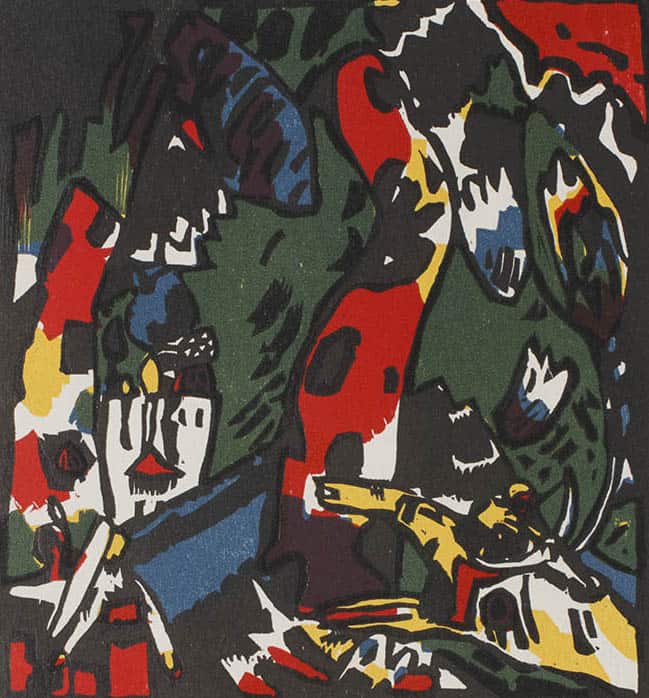

Around Saitō’s scene, near-contemporaries overlap, some of them familiar to visitors to the museum over the years. Beside his palace, a castle rises on a steep slope in woodblock print in vivid color, reds and yellow, forest green — Vassily Kandinsky’s The Archer.

Vassily Kandinsky's woodblock print of The Archer suggests steep gorges and a rider speeding toward a castle in pulsing color. Press image courtesy of the Clark Art Institute

His abstract scene holds a suggestion of deep gorges, stone towers and a mounted bowman galloping toward refuge but turning and aiming his bow behind him, as though he is pursued.

Guest curator Oliver Ruhl drew a connection between the two artists in his Competing Currents exhibit at the Clark in fall 2021, seeing a kinship in their color and texture and experimentation. (The Clark has traced connections between Japanese artists and Impressionists and Modernists in both directions.) And here they are side by side.

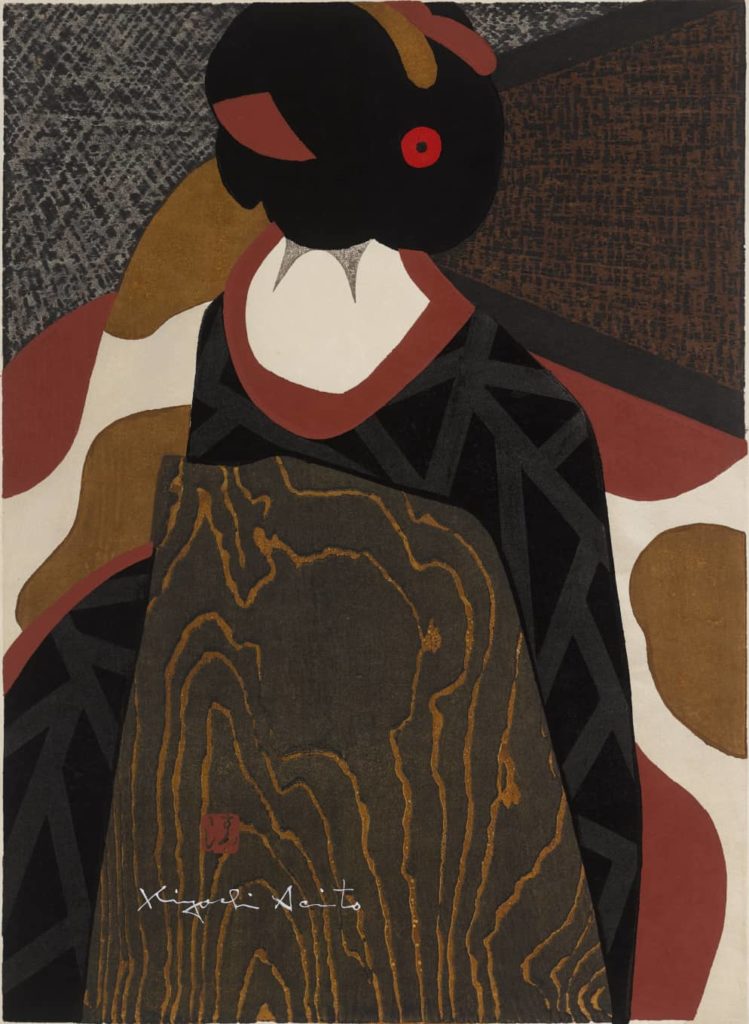

In 1938, when Saitō issued his first prints in his “Winter in Aizu” series, Kandinsky was living in Paris at the height of his career and painting biomorphic abstract forms. Saitō would become known around the world for his own earthy, half-abstracted scenes, and his processes he evolved, working with woodblock prints he carved and inked himself.

And both artists lived in countries shaken and divided by World Wars. Japan was facing rapid change, forced intrusion and influence from the West. Kandinsky left Russia for Germany and then France, and evolved his own unique forms of painting before and after World War I — gliding on the leading edge of abstraction.

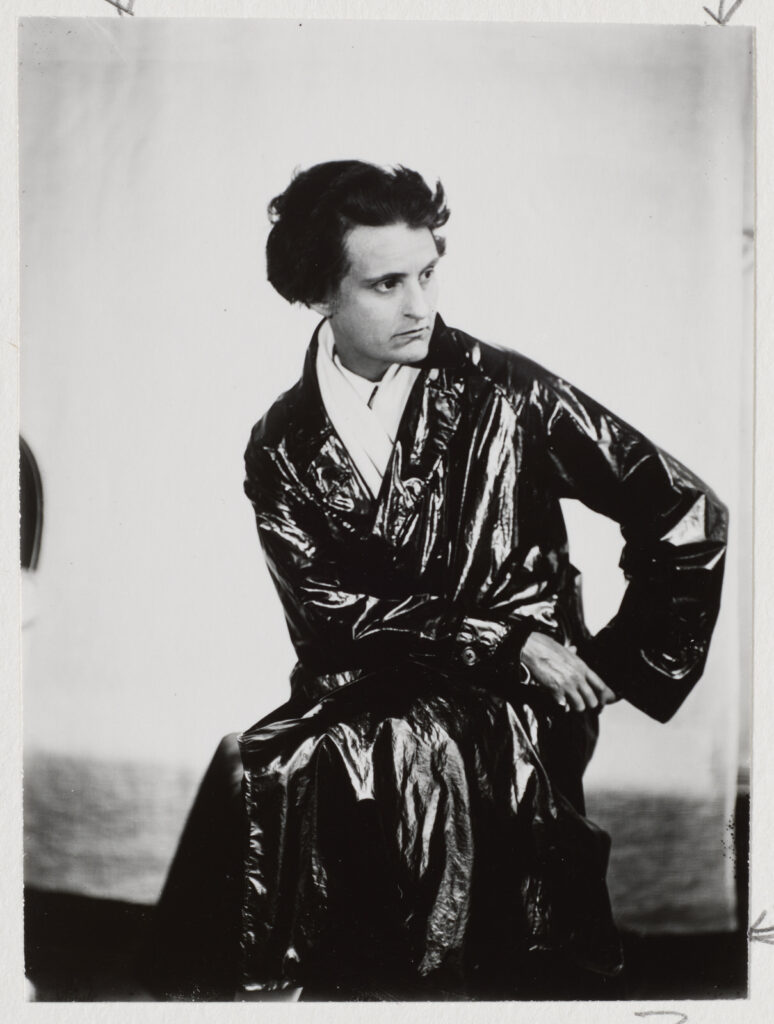

Beside them here, photographs take the pulse of Paris between the wars. While Kandinsky was teaching at the Bauhaus, Berenice Abbott was living in France and taking portraits of friends in the Quarter Latin — journalist and novelist Djuna Barnes, and Sylvia Beach, founder of the Shakespeare and Company bookshop.

They were living at the hub of a community of writers and artists, flowing between Shakespeare and Company and a companion across the street, one of the first French bookstores founded by a woman — Adrienne Monnier opened La Maison des Amis des Livres, the home of friends and books, in 1915, in the chaotic Paris of World War I, with the front lines and the trenches less than 50 miles away.

Sylvia Beach, founder of the Shakespeare and Company bookshop in Paris, and freelance journalist and novelist Djuna Barnes look freely into the lens in photographs by Berenice Abbott.

Juxtapositions like these invite questions. How did Sylvia Beach and Berenice Abbott meet … and what would it have been like to come to a reading on the rue de l’Odéon?

With the war barely five years behind, what conversations could they have heard when Beach was publishing James Joyce’s Ulysses, and Adrienne Monnier was gathering writers for an international journal, Le Navire d’Argent (The Silver Ship), which would carry Walt Whitman, Rainer Maria Rilke, Antoine de Saint-Exupéry?

In the timeline unfolding in this show, these artists and writers are overlapping and following in the footsteps of a generation women who came to Paris to paint. Impressionist artist Elizabeth Nourse captures a moment of love between sisters. She was still painting in her studio when Abbott’s photographs were taken.

Art across generations

Elizabeth Nourse’s direct self portrait of herself painting at the easil appeared at the Clark Art Institute in Williamstown in Women Artists in Paris 1850 to 1910. Saito Kiyoshi’s print Maiko, Kyoto, shows a woman from behind, as she sits in a silk robe and the grain of the wood from the print block ripples in her sash — his prints have appeared in exhibits at the Clark in 2016 and 2021. Press photos courtesy of the Clark Art Institute.

Rosa Bonheur's Plowing in Nivernais appeared at the Clark Art Institute in Williamstown in Women Artists in Paris 1850 to 1910. Press image courtesy of the museum

Nourse she had stayed in Paris through the war. But her roots in the city stretch back to the 1880s and 1890s, to Paris of Van Gogh and Berthe Morisot. When artists gathered here from Europe and America, she was studying among them. She established her own studio, exhibited at the salons, and became the first American woman to be voted into the Société Nationale des Beaux-Arts.

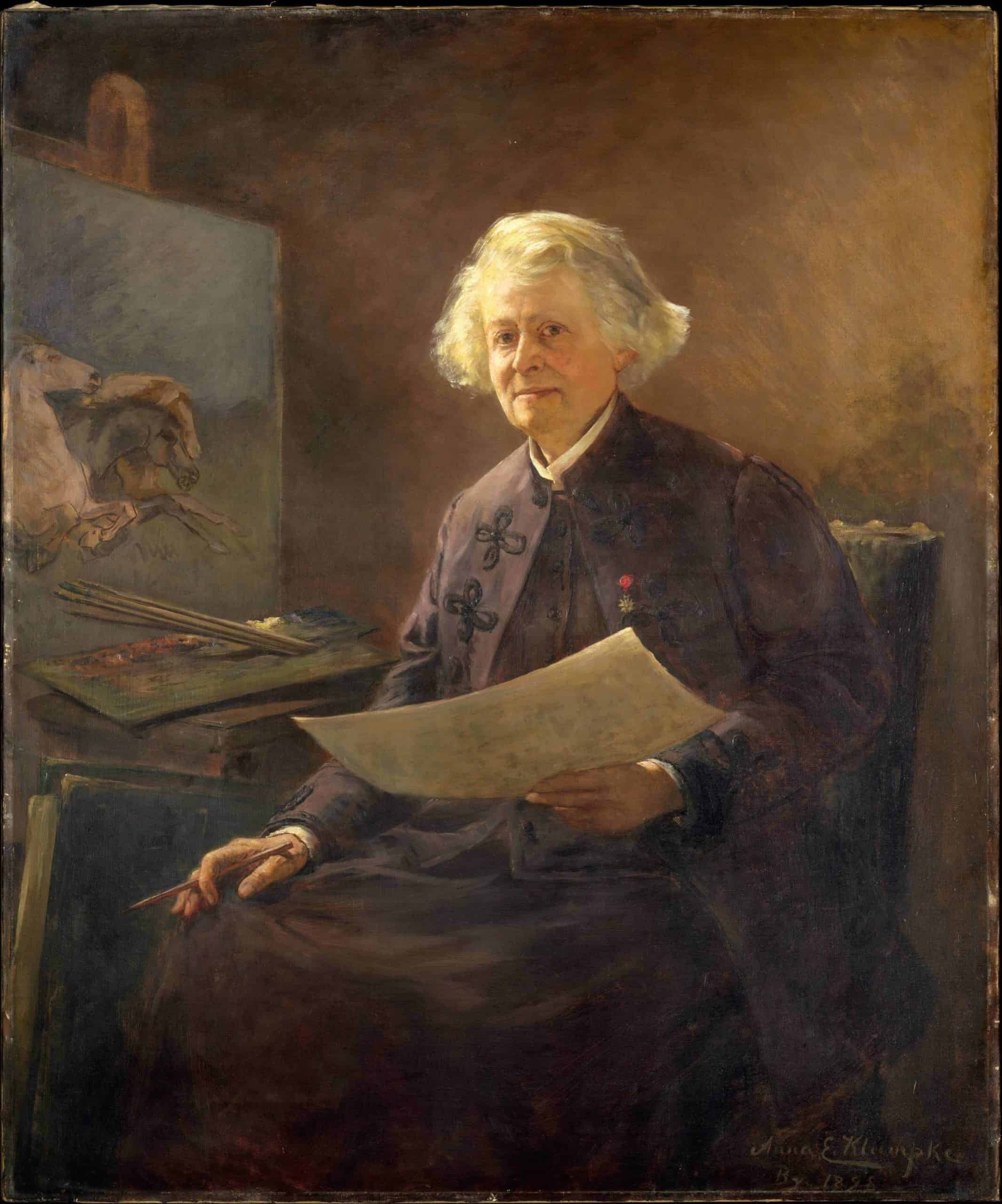

Anna Klumpke's portrait of the internationally known Parisian artist Rosa Bonheur appeared at the Clark Art Institute in Williamstown in Women Artists in Paris 1850 to 1910.

She appeared in this room too, in summer 2018 in Women Artists in Paris, 1850–1900, in an exploration of the women in her world. Mary Cassatt appeared with her then, as she does here today, holding international recognition among the Impressionists, and so did Rosa Bonheur, who won the Legion d’Honneur and became known as one of the most influential artists in France.

This winter Bonheur sketches a lion. Bonheur seems to have been widely known for her vigor and the power of her work. She won the admiration of novelist Victor Hugo (writer of Les Miserables), and Georges Bizet (composer of Carmen) wrote a cantata for her. And she loved the natural world. She fought to preserve Fontainbleu Forest. And she knew animals up close.

Anyone coming into this room in summer 2018 would have seen her work large and in color, horses moving with muscled strength along a hillside, alongside Nourse’s self-portrait — a woman painting at a canvas, strongly sunlit and immersed in shades of deep red.

Between Impressionists, the show moves back across the Atlantic and through time. Berenice Abbott is coming home to New York. Glimpses of her work give flashing snapshots of the artistic worlds she lived in, and they prompt investigations.

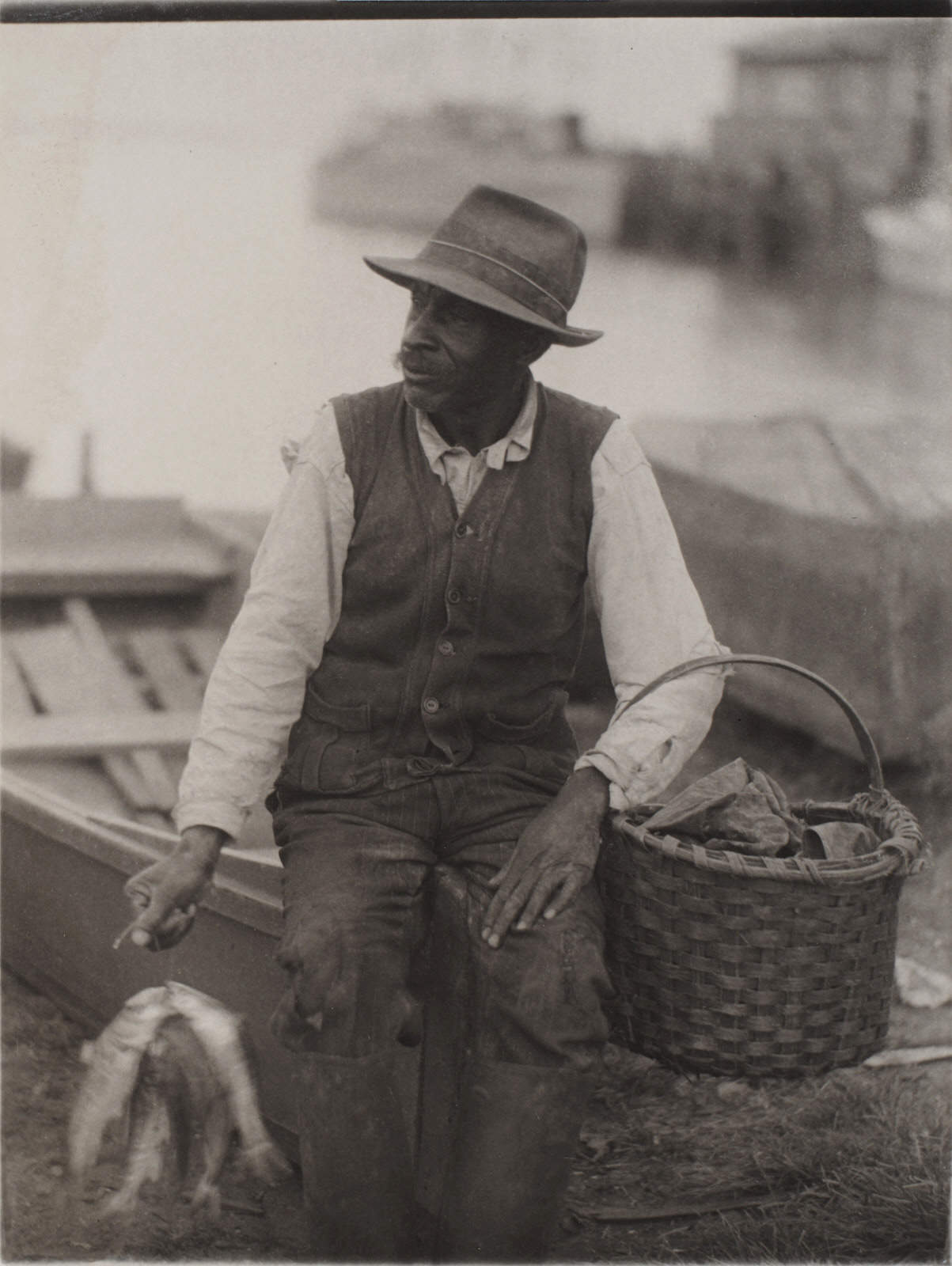

A man sits on the bow of a dinghy, holding a string of freshly caught fish, in Doris Ulmann's 1925 photograph Fisherman, South Carolina. Press image courtesy of the Clark Art Institute

In the 1910s, she had lived in Greenwich Village — she was sharing a house with Barnes and friends, and Barnes was writing freelance, walking through Brooklyn markets when farmers from Long Island brought their beets and onions by horse and cart, talking with Suffragists as women finally won and secured the right to vote.

Between the wars, Abbott returned to become part of an internationally respected community of New York photographers.

While she was catching scenes from urban life with the WPA, James Van der Zee was creating images in the Harlem Renaissance, and Doris Ulmann traveled from the city to Appalachia and the rural South.

Photographs give way to prints and move earlier in time, until with a jolt, images from 18th-century Spain are presenting a debate as contemporary as the daily news. Fransisco de Goya is giving an incisive critique of dehumanizing influences in his world, in scenes as abstracted and dreamlike as a surrealist French poet’s.

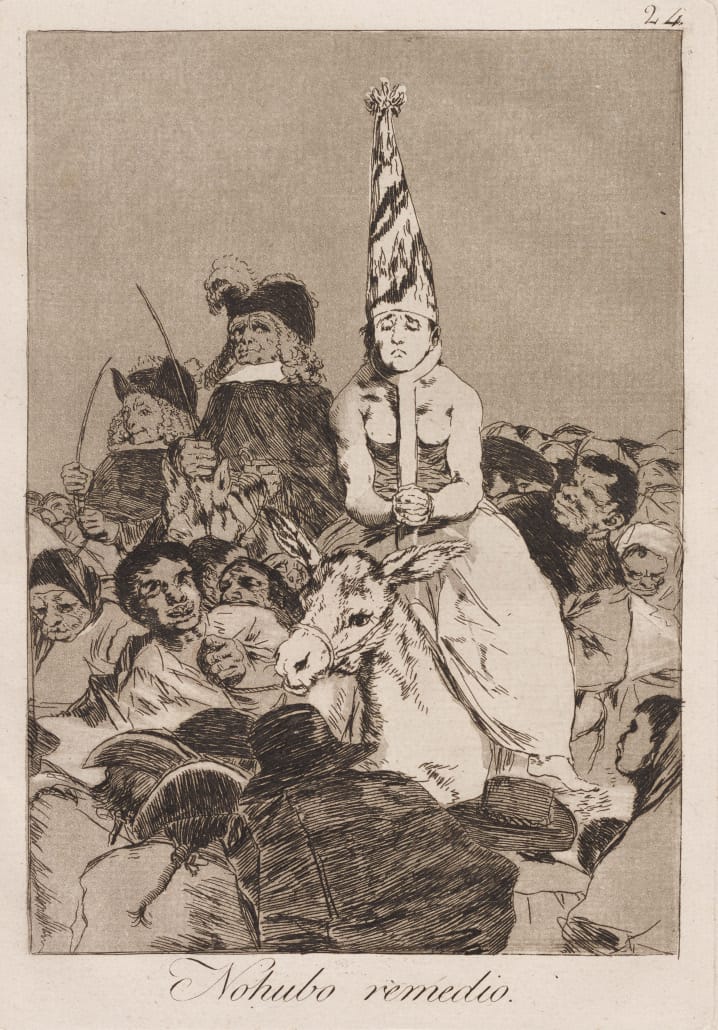

A rider on a donkey suffers at the hands of the Spanish Inquisition in Fransisco de Goya's etching No Hubo Remedio, There Is No Remedy. Press image courtesy of the Clark Art Institute

Faces leer around the quiet courage of one central figure, in an aquatint etching from Los Caprichos (a series of satirical images familiar to anyone local who saw Noche Flamenca perform last spring at Williams College).

A rider on a donkey is moving through a mocking crowd. The rider sits with dignity, back straight, with a tension that looks like force of will and an expression of concentrated sadness. And they are wearing an iron band around their throat, joined to a bar across their breast that shackles to their wrists.

The U.S. uses the same restraint today. And this one comes from the Spanish Inquisition.

The rider wears a tall, conical hat and tunic, a clear sign to Spanish readers at the time (according to the Prado in Madrid) that the Inquisition has already condemned them. The crowd have come here by choice to torment them with public humiliation. Goya has called this work There is no cure.

In this gathering though, in this gallery today, he stands with Rosa Bonheur and Adrienne Monnier, Elizabeth Nourse and Djuna Barnes. And his images and ironic titles seem to invite speculation. Would he say the same now? If he and Berenice Abbott met over coffee with Vassily Kandinsky and James van Der Zee and Saitō Kiyoshi … how would Goya describe his dreams?

What would they all say to each other if they could meet in the rue de l’Odéon tonight, or in North Adams at the Bear and Bee Bookshop, and Djuna Barnes could walk through town with a notebook in her hand, listening?